Swiss pharma giants swallow up start-ups in push for next big gene therapy

Swiss drug makers are increasingly relying on buying science rather than doing it themselves, with taxpayers footing some of the bill for big discoveries. The investigation by Swiss public television comes as Novartis announces it is reconsidering a lottery program to distribute free-of-charge the most expensive treatment ever developed.

When the US Food and Drug Administration approved Zolgensma last year, the one-time gene therapy treatment for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), a debilitating and often deadly genetic disease especially prevalent among young children, it was the price tag that received much of the attention. At $2.1 million (CHF2.1 million) the one-time infusion was billed as the most expensive treatment ever.

It is unlikely to remain so: over 200 cell and gene therapies are currently in development, raising concerns about how over-stretched health systems are going to afford to pay for these “miracle” cures.

+ More about the most expensive treatment ever

In a marked shift from how companies used to defend high prices by pointing to the cost of R&D, Novartis has justified the price based on the value it brings in terms of additional years of life, quality of life and cost savings to health systems.

SMA in Switzerland

Between five and ten children are born each year in Switzerland with spinal muscular atrophy. Generally, one in 10,000 newborns is affected.

But this has left lingering questions about how much money Novartis and other big pharma companies are making from such treatments and who is ultimately footing the bill for their discovery.

An investigationExternal link by Swiss public television RTS published on Sunday found that big pharmaceutical companies are relying more heavily on buying smaller companies with drugs in advanced stages of development rather than investing in their own science.

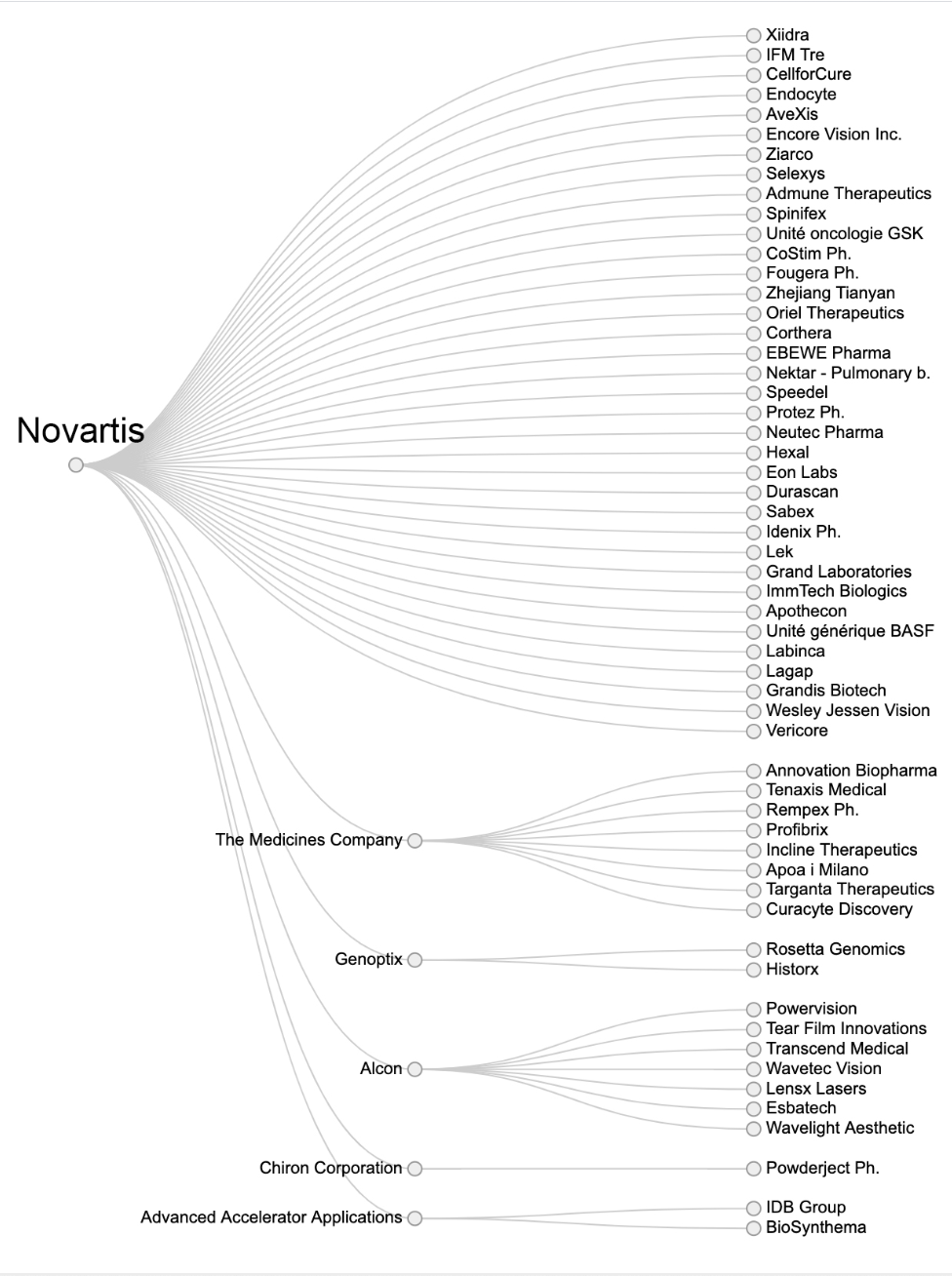

Of the 16 big pharmaceutical companies RTS investigated, Roche and Novartis relied the most on acquisitions with 49 and 45 companies swallowed up by the Basel-based health giants respectively since 2000.

The case of Zolgensma

Zolgensma’s history is illustrative of a larger trendExternal link in the industry whereby treatments pass through the hands of different researchers, many financed by universities, charities or taxpayers, before they are purchased in late stages and end up in a multinational’s pipeline.

In 2007, a team of French researchers at the non-profit research institute Généthon, financed by the Téléthon charity, found a way to transmit healthy genes to patients through a virus vector. When it was time to turn their discovery into a drug, they were overtaken by the US start-up AveXis, which invested CHF530 million, bought the patent and passed several stages, including clinical trials on humans.

In 2018, Novartis swooped up AveXis and the rights to market Zolgensma for CHF8.7 billion, a year before the treatment was approved for use in the US. With the purchase, Novartis also added critical gene therapy capabilities, particularly in neuroscience.

However, the difference between the CHF530 million and the purchase of AveXis at a 72% premium of its average stock price, and then the ultimate $2.1 billion price tag for Zolgensma has raised eyebrows. While Novartis says that it and AveXis have invested over $1 billion in the development of Zolgensma including costs for extending clinical trials and manufacturing facilities, the company didn’t bear risks inherent in the early stages of drug discovery.

Moreover, not only was Généthon financed by non-profit patient association but the founder of AveXis received $6.3 million in public funding for his research in the US over his career. Another patent it acquired also received nearly $120 million in US public funding.

Research by acquisition

Zolgensma is not an outlier, according to the RTS investigation. Of the 39 new active ingredients validated since 2018 in Switzerland by major pharma companies, at least 27 have been bought at an advanced stage of development (phase 3 clinical trial). Only 30% of these drugs were therefore discovered in the laboratories of the major companies.

For Novartis, none of the six preparations recently approved in Switzerland were developed in the Novartis laboratories. In its pipeline, RTS found that 27 were the result of acquisitions while only 22 could be considered ‘in-house’ products.

A Novartis spokesperson told swissinfo.ch that “like any large pharmaceutical company, our portfolio contains programs that have been in-licensed, but we believe that it is correctly balanced with innovative medicines emanating from our labs.” Treatments discovered and developed internally in recent years include arthritis pain-reliever Consentyx as well as Mayzent to treat multiple sclerosis.

Novartis added that it invests roughly CHF9 billion in R&D annually, which is among the largest R&D budgets in the industry. Over one third of this amount is spent in Switzerland.

Acquisitions by Novartis. For the other sixteen companies see hereExternal link.

While Novartis and Roche top the list in terms of number of acquisitions, buying promising drugs from outside to boost sales is a strategy being pursued by several others, which is driving up prices.

In 20 years, the 16 groups analysed by RTS have acquired 315 companies exceeding a sum of CHF1.2 trillion. This includes US company AbbVie’s purchase of Pharmacyclics for over CHF20 billion in 2015 and Gilead’s acquisition of Kite Pharma for CHF11 billion to secure access to Yescarta, a gene therapy treatment against a type of lymphoma.

According to Bertrand Kiefer, a physician and editor-in-chief of the Swiss Medical Journal, “companies are competing with each other, which drives up prices.” He adds, “It is necessary to get out of this unhealthy and unethical climate in the health sector. This isn’t about an iphone with an improved screen. This is about children’s lives.”

See the full RTS storyExternal link for information about the methodology.

Controversial lottery

In December, Novartis announced that it was launching a Managed Access Program for Zolgensma to enable access to the treatment in countries outside the US where it had not yet been approved for use by local health authorities. As part of the program, the company would allocate up to 100 doses a year for free by randomly selecting medically eligible patients.

In a statement to swissinfo.ch, Novartis explained that the program was anchored in principles of fairness, clinical need and global accessibility to best determine the equitable global distribution of a finite number of doses that doesn’t favour one child or country over another.

However, the lottery style program drew significant criticism from some patient advocacy groups and health authorities, who argued that it could have devastating emotional effects on families and that there were still questions about the safety of the treatment.

In an interviewExternal link in the NZZ am Sonntag, medical ethicist Tanja Krones from the University Hospital Zurich argued that governments should be the ones that negotiate distribution and not the company directly with individual doctors and patients in any country.

In a letterExternal link dated February 5, Novartis announced that it is reconsidering the design of the program in collaboration with patient advocates and clinicians.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.