How Palau’s archipelago forms a democratic whole

This is the story of how a small, independent country spread across several hundred islands – some with just five eligible voters - manages to have every vote counted and every voice heard.

The fascinating ride starts on approach to the Micronesian archipelago of Palau, home to 20,000 people and located southwest of the Philippines. As our plane prepares to land at Koror International Airport, the nation’s world-renowned Rock Island area comes into view.

Listed as a World Heritage site since 2012, this group of about 300 limestone and coral outcroppings creates a fitting welcome to those visiting the Pacific archipelago.

I’m here as part of my democracy world tourExternal link to discover how this 190th member state of the United Nations has used its sovereignty to create a unique democratic model.

At immigration, I have a “personal pledge to the children of Palau” stamped into my passport. It starts with the words, “I take this pledge as your guest to preserve and protect your beautiful and unique island home. I vow to tread lightly, act kindly and explore mindfully”.

Last December, Palau became the first country in the world to require incoming guests to adhere to such a commitment of active and responsible citizenship. The country can take legal action against visitors who break the conditions of the signed pledge in their own passports and may even issue fines of up to $1 million (CHF926,760) for doing so.

The reason behind the pledge is the rapid increase in tourists coming to Palau, especially from China. This has created a strong backlash from locals.

“If we do not act now, our paradise will soon be lost,” says my Palauan host after picking me up at the airport. “The influx of fast cash from China is a big challenge for us.”

Powerful citizens of Palau

Palauans have faced such challenges before. The first settlers from the country’s closest neighbour, the Philippines, came over around 3,000 years ago, while European explorers showed up in the 16th century. The Spaniards and the Germans included Palau in their colonial schemes, while the Japanese conquered the archipelago during the First World War and the United States added the islands to its Trust Territory of Pacific Islands in 1947.

But the island nation’s citizens remained resilient amid such influences, emerging with a pre-modern form of democratic federalism containing fine-tuned structures of power division.

Equality between men and women has also long been a cornerstone of the nation’s politics.

While the traditional chiefs of the villages (known as “hamlets”) and states always have been men, women have been in charge of selecting those chiefs.

“Women in Palau have always played a very important role in society,” says Ann Pedro, a clerk for the country’s Senate. I met her at the National Capitol Hill, a political forum established a decade ago in the middle of the rainforest on Palau’s biggest island, Babeldaob.

Palau’s per-capita annual income is on par with China, at about $16,000. It is home to some 20,000 people.

The country’s official languages include Palauan, English, Sonsorolse, Tobian and Japanese.

Palau covers more than 500,000 square kilometres of sea but just under 500 square kilometres of land.

Having observed how alienated many other former colonies and remote island nations have become from their own heritage, it is truly uplifting to come here.

The people of Palau have used their limited possibilities to link their proud societal heritage with modern-day democracy. The traditional states were incorporated into the federal republic through a series of constitutional referendums during the 1980s and early 1990s.

‘House of Whispered Decisions’

While Palau is considered a micro-state by population and size, its political system takes influences from both the US, with its two equal parliamentary chambers a directly elected president, and Switzerland’s mandatory constitutional referendums and citizens’ initiatives.

In recent years, Palauans have been called to decide on more than 40 reform amendments to their national constitution. This is complemented by elections to all mayoral offices at the federal level as well as throughout the 16 states making up the nation.

The National Capitol Hill compound showcases Palau’s impressive political infrastructure, with an estate composed of both the traditional “Bai” (the meeting and assembly house of the chiefs), and buildings for the three main powers of the legislative, executive and judiciary.

In recognition of its unbroken democratic traditions, the two-chamber parliament is called the “Olbiil Era Kelulua” – or the “House of Whispered Decisions”.

$35,000 expedition for five votes

Another critical institution, the Palau Election Commission, is located in a far more humble and difficult-to-find setting: a metal hut south of the island’s main town of Koror.

Here, Maria Decherong carries out the job of “Election Services Administrator”. She and her colleagues manage a quite sophisticated operation.

“Each and every one of our 16 states have their own parliaments and constitutions, but we have to ensure that every vote is counted even in those elections,” Decherong says.

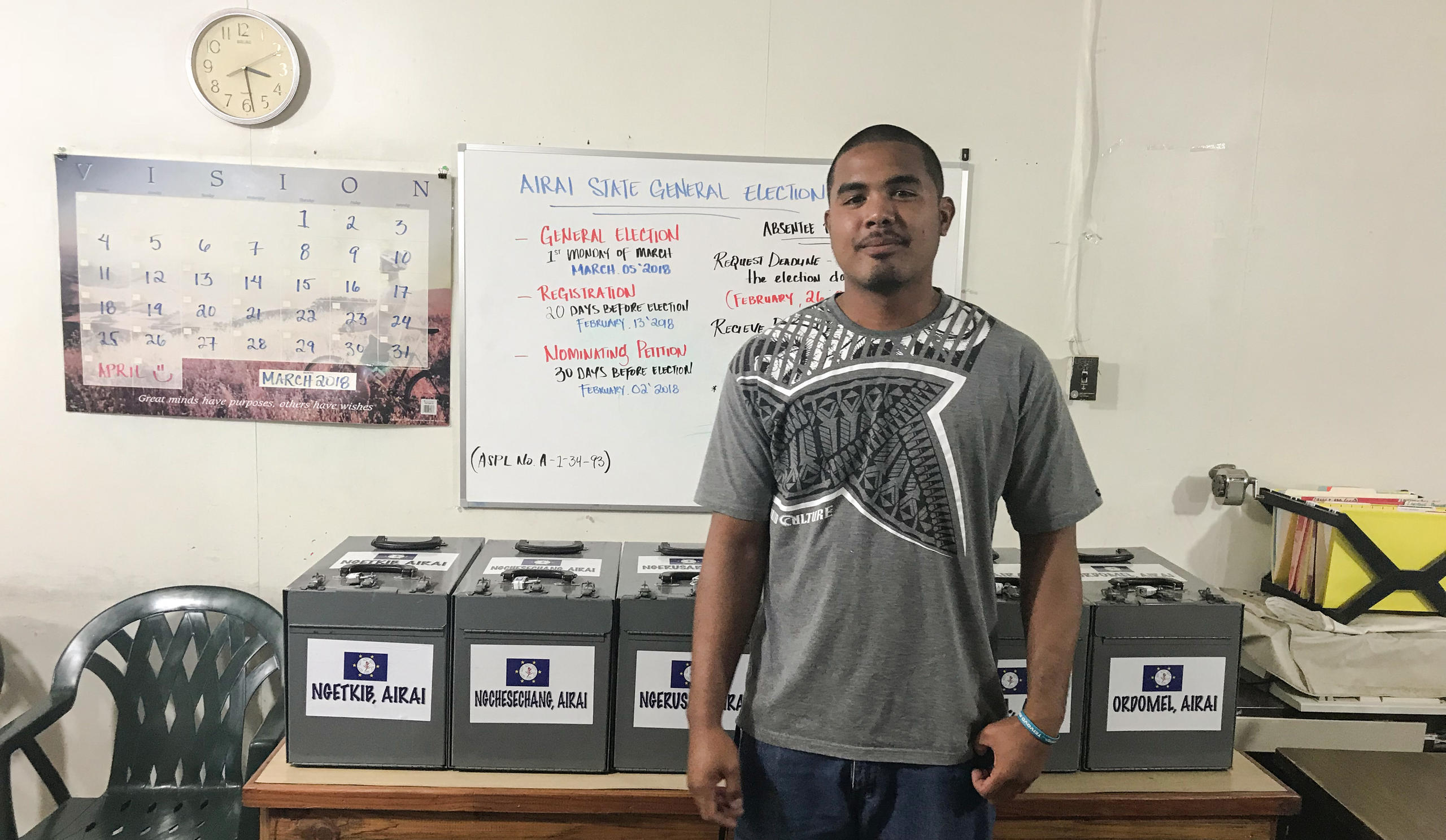

Airi state, the country’s second-most populated state with just under 1,500 eligible voters, is about to elect a new governor and parliament on March 5.

“We do most work manually but have two scanners for the vote counting process which we purchased after independence in the late 1990s,” Decherong explains. A great challenge to her work is the geographical distribution of the 16 states.

“When we have to get the five votes from Tobi island in the far south, I need to invest in an adventurous ship expedition of at least a week that costs at least $35,000”, she says.

But the people of Tobi (formally called “Hatohobei State”) have their votes counted every time, since they are allotted one representative in the State Capitol House of Delegates just like all other Palauan states. The country’s Senate is elected nationwide, while the House contains one representative per state.

Reaping democracy’s fruits

The Palauan commitment to democracy has so far produced some rather impressive results: its seas became the world’s first international shark sanctuary, and two years ago the resource-rich Economic Zone of Palau was declared a no-take Marine Sanctuary in which no fishing is allowed.

Close to the coast lines, however, local fishermen are still allowed to provide products for the domestic market.

In contrast to other Pacific nations which stock considerable amounts of unhealthy canned food from far away, shops in Palau offer many great local dishes from across the islands including vegetables and fruits likes taro, tapioca and coconut. (And there is a great domestic amber beer called “Red Rooster”).

The very existence of such a strong democratic society, which both shares and cares about the future of its own country within the global ecosystem is greatly encouraging.

Palau will host the global “Our Ocean Conference” in 2020. It will be an opportunity to make people from all walks of life, heads of state, investors, civil society activists and scholars sign the forward-looking Palau Pledge, which concludes with the words:

“I shall not take what is not given. I shall not harm what does not harm me. The only footprints I shall leave are those that will wash away”.

Swiss-Swedish author and journalist Bruno Kaufmann is on a world tour to explore the state of democracy visiting more than 20 countries on four continents until May 2018.

swissinfo.ch has been publishing a weekly Notebook and multimedia reports by Kaufmann as part of its coverage of direct democracy issues.

Kaufmann’s democracy world tour is mainly sponsored by the Swiss Democracy FoundationExternal link, where he is the director of international cooperation. The Swiss Democracy Foundation hosts various projects and platforms linked to participatory and direct democracy across the globe, including Democracy International, External linkthe Direct Democracy NavigatorExternal link and the Initiative and Referendum Institute Europe.External link

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.