Why are Swiss child services so disliked?

Child protection authorities are among the most unpopular institutions in Switzerland, even after recent reforms. Why the backlash?

Overshadowed by the dark past of so-called “slave children”, Swiss child protective services were subject to sweeping changes in 2013. But their reputation has continued to suffer after a series of incidents, notably a mother who killed her two children to stop them from being taken into care.

A popular initiative now in the pipeline aims to clip the wings of child protection authorities.

Erika* de Winterthour was 16 when she got pregnant in the late 1990s. In Switzerland, the child of a mother under 18 is automatically put into care. Erika remembers there were discussions with the authorities at the time to see if someone in the family could be the guardian, but she said the family decided it would be better to have someone official from the child protection service. Erika was very pleased with the way the service represented her daughter in a court battle with the father over child support.

At first, the young mother was surprised that the guardian did not come to make sure she was doing everything right with the baby. “So I simply invited her to supper,” says Erika, who remembers the experience positively. On her 18th birthday, she was given back custody of her daughter without a problem. But, she says gravely, “I think it would be different today – not as straightforward, uncomplicated and humane as it was for me.”

Too much bureaucracy?

Erika now works as an assistant in a home for physically and mentally handicapped people, where she has the impression that everything has become more bureaucratic.

“The parents of handicapped people who resume charge of their adult children are sometimes overwhelmed by the amount of paperwork they must do,” she says.

Indeed, one of the most frequent criticisms of the Child and Adult Protection Agency is that it has created a mountain of bureaucracy. People who have dealt with it say things no longer work the way they did for Erika. They say the authorities no longer check to see if a family member can step in as a guardian, that they do not involve the people concerned in decisions, that they sometimes intervene in an insensitive way in families where things are working, and that anyone caught in the agency’s net will never get out.

In short, the child protection authorities may well be among the most-hated institutions in Switzerland.

Dramatic cases

But why? In 2013, Switzerland’s 100-year-old child protection law was completely overhauled. The new child protection service was professionalised and made independent from the political authorities.

Whereas previously the role of guardian was mostly played by the local authorities – especially in German-speaking Switzerland – the new Child and Adult Protection Agency is composed of lawyers, social workers and psychologists. They are the ones who decide whether a child should be placed outside his or her family, if a mentally handicapped person is unable to make certain decisions or if an elderly person with dementia should be placed in a home.

But various dramatic incidents have undermined the image of the new agency in recent years. In Flaach, canton Zurich, a 27-year-old mother killed her two children so they would not be returned to an institution, while an 88-year-old man fled to Germany with his nephew’s help to avoid being put in a home. A father also helped his wife and two children flee to the Philippines so the children would not be placed in care by the authorities.

There have also been media reports of more frequent occurrences, such as a family having to pay CHF5,000 ($5,345) a month that it could not afford to pay for a 17-year-old daughter in care, and authorities designating costly professional care for the elderly when a relative could have assumed the role for free.

Discontent is mounting in certain sectors of the Swiss population. There have been several calls in parliament for more transparency, more legal guarantees and more rights for relatives to be heard. In the central Swiss canton of Schwyz, a popular initiative to return child protection cases to the local authorities was rejected only by the narrowest of margins. And another initiative is in the pipeline, this time at federal level, which would give family members priority as guardians and carers.

The shadow of the past

Child protection expert Christoph Häfeli is surprised at the virulence of criticism against the new Child and Adult Protection Agency. He believes many things have changed for the better, with overworked non-professionals no longer deciding on the fate of their neighbours, as was sometimes the case in the past.

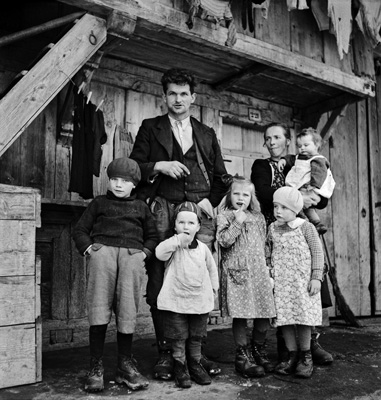

Also, it was under the old system that the darkest chapter in Swiss child protection history took place. From the 1940s to 1981, tens of thousands of so-called “slave children” were taken from their families and forced to work on farms or live in foster homes after their families were deemed unfit to look after them. Roma people saw their children taken away for “re-education”, while single-parent children and orphans often suffered the same fate.

More

Who were Switzerland’s ‘slave children’?

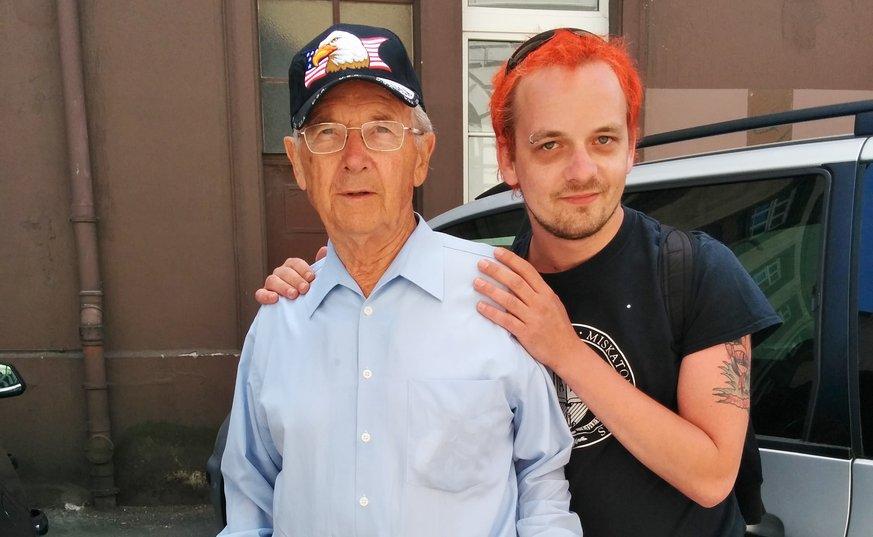

Guido Fluri, a successful businessman who was put in care as a child, launched an initiative to get reparations for the “slave children”. As a result, victims started receiving compensation payments in 2018.

After the flood of criticism levelled at the child protection agency, Fluri launched a help centre for people affected by its work. Many of the calls are about the agency’s professional guardians, as well as conflicts between parents over child visiting rights. But Fluri says the new system works well in most cases.

“The new law on child and adult protection has brought considerably more professionalism,” he says.

He does see potential for further improvement, notably through better communication with the people concerned. But Fluri cannot imagine a return to the old system where the local authorities held sway.

“Those who remember the measures imposed in the past and the suffering they caused cannot say that things were better before.”

A costly institution

So why such big opposition to the new child protection agency? Fluri thinks the terrible infanticide in Flaach is one big reason, because the public and the media were quick to blame the authorities.

For Häfeli, one of the main reasons for the agency’s unpopularity is the cost of professional help.

“Professionals are clearly more expensive,” he says, “but you don’t get quality for free.”

And he says the public perception that the authorities often choose costly professionals over family members is not reflected in the figures.

“In Switzerland, there are 28,000 private and 8,000 professional caregivers,” he says. But he does not deny that the cost of professional help is rising.

Those concerned must pay for the care themselves or, if they cannot afford it, they can get help from local authorities.

But that can cause yet another problem.

“Before, it was the same authorities that decided protection measures and paid for them,” says Häfeli. “Now it’s the protection agency that decides and the local authorities that pay.”

So whereas the previous child protection authorities had a financial interest in keeping care placements down, that is no longer the case. In 2016, the number of protection measures decided for both children and adults rose.

But the number of overall cases has been on the rise since well before the 2013 reforms. Häfeli argues the current system allows for keeping a closer eye out for children and people needing protection, which is fundamentally a good thing.

Adapted from the German by Julia Crawford

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.