If you want the Olympics, do not ask the people

Switzerland is not the only nation to have discovered that the Olympic Games and democracy have become incompatible bedfellows. This is unlikely to change any time soon.

“And the winner is … Beijing.” This summer’s announcement by the president of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), Thomas Bach, of the hosts of the 2022 Winter Games was met around the world by a large sigh.

Staging the world’s biggest winter sports event in a smog-ridden megalopolis without any snow and a record of human rights violations during the 2008 Summer Games in the same city – frankly, it doesn’t seem a very good idea.

However, the choice of candidates for the 2022 Games had become so limited that the only remaining contender besides Beijing was Almaty, a city in south-east Kazakhstan, another Asian dictatorship.

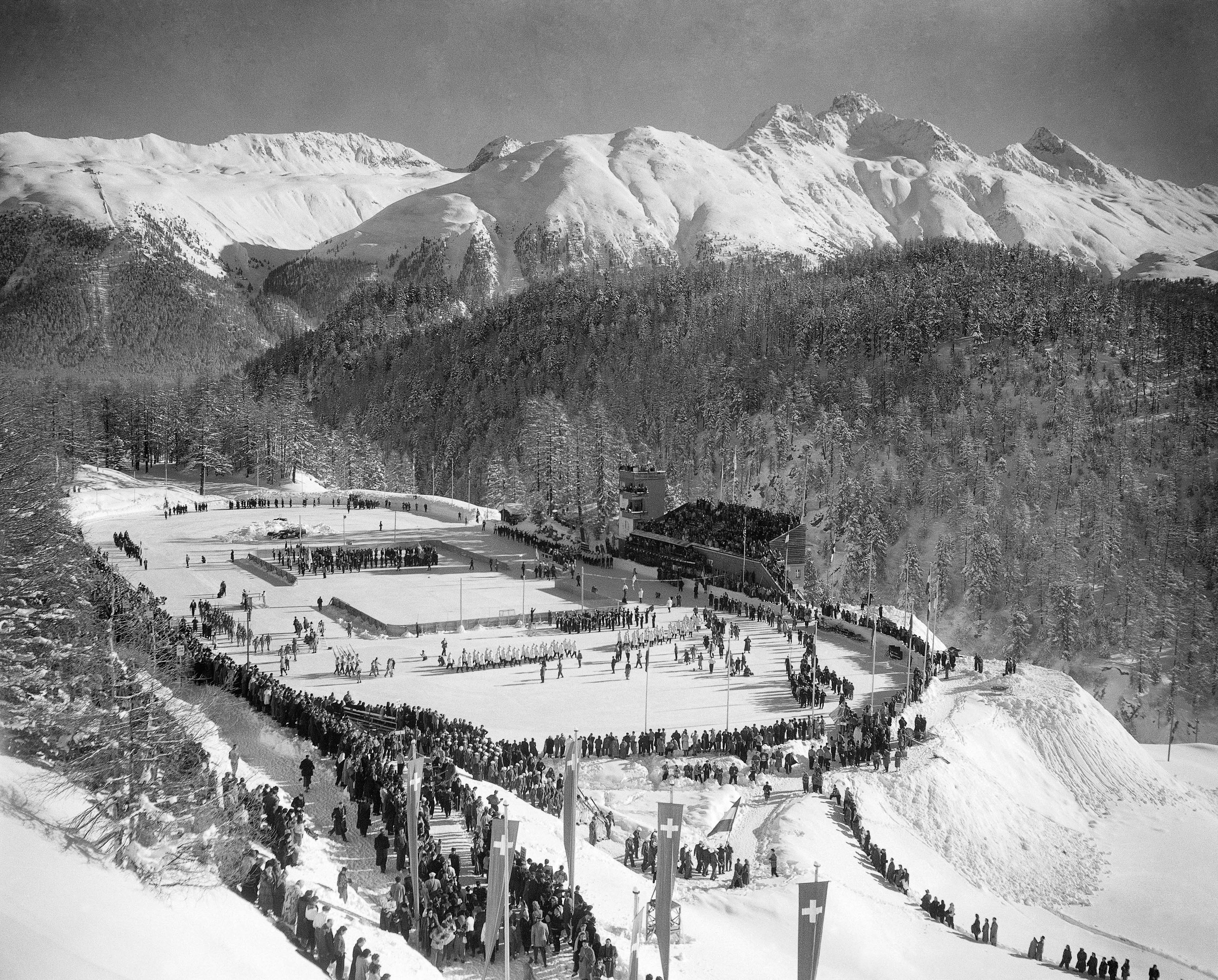

Munich (Germany), St Moritz-Davos (Switzerland) and Kraków (Poland) had pulled out as a result of public votes on the issue. Stockholm, Lviv and Oslo all dropped their 2022 winter bids due to lack of local support.

Attempts to reconcile the idea of the Games with democracy have become extremely difficult. Nobody knows this challenge better than the people of the Swiss canton of Valais.

Four times in recent decades, organisers tried to bring the Winter Olympics to this mountainous region of Switzerland. Four times citizens had their say at the ballot box.

Back in 1963 it was a narrow “no”. But they voted again on new projects in 1969, 1995 and 1997 and an overwhelming majority said “yes” to the idea of hosting the Games in their canton.

Yet this appeared to do nothing to sway the IOC. On the contrary, the committee awarded the Games to other cities and regions around the globe. (Ironically the 1976 Games, which the IOC had given to Denver/Colorado, ended up in the Austrian resort of Innsbruck after a late negative vote by Denver citizens in 1972.)

Now that the much smaller Youth Olympics in 2020 has gone to Lausanne, Swiss sports officials are looking into launching a fifth attempt for the regular Games.

By the people, for the people

All this is as irritating as many other current issues linked to the IOC and the Olympic Games.

But from the outset it seemed to be an ideal match. Both the Olympics and democracy have similar roots. They were born out of the idea of people power and broad participation in ancient Greece, while the IOC is now headquartered in one of the world’s most vibrant and direct democratic cities: Lausanne in Switzerland.

For a long time the modern Summer and Winter Games – resumed in Athens in 1896 and organised 49 times since then (27 in summer and 22 in the winter season winter) – had little to do with big money and elite sports.

Opinion series

swissinfo.ch publishes op-ed articles by contributors writing on a wide range of topics – Swiss issues or those that impact Switzerland. The selection of articles presents a diversity of opinions designed to enrich the debate on the issues discussed.

That has changed dramatically. The number of participating athletes and nations has multiplied and modern media have globalised the event. Budgets of more than $50 billion (CHF49.2 billion) like in Sochi, Russia, at the 2014 Winter Olympics fly in the face of all assertions of “small is beautiful”.

On top of that, the IOC’s record of obscure accounts and lack of transparency have become a major “piece of resistance”.

List of demands

The most recent bidding processes for the 2022 Winter Games is a strong case in point.

In Oslo, the capital of oil-rich Norway, citizens endorsed the candidature in the city’s first referendum ever in September 2013.

But the IOC’s prima donna-like demand for a hefty deficit guarantee left no choice for the government.

In a 7,000-page handbook, the IOC requested – to give just a few examples – cocktail parties with the Norwegian royal family (with the royals expected to pick up the bill), public bars to remain open during the night and exclusive lanes for the vehicles of the sports officials.

Being asked to invest billions of taxpayers’ money in an event for the elite by the elite is a very hard sell for a country which hosted probably the last down-to-earth and highly successful 1994 Winter Games in Lillehammer.

It also shows that it has become a non-starter for every successful Olympic bid to involve the people in the process of preparing and organising the Games. This is because a minimum level of transparency and accountability is required for an open procedure, regardless of whether a majority of the citizens supports the idea or not.

More votes

With the bidding for the 2024 Summer Olympics in the final stages these questions have gained additional importance.

Boston, the frontrunner in the United States, pulled out when the timing for a possible statewide referendum in Massachusetts became clear.

A likely vote in 2016 would have handed critics a golden opportunity to stop the bid.

In Europe, Germany’s national Olympic Committee chose Hamburg (over Berlin) to apply for the 2024 Games because it saw better chances of winning a public approval in the North Sea city.

Hamburg’s parliament has now even amended the constitution to allow for a public vote which is initiated by the parliament itself.

This top-down plebiscite is scheduled for November 29 this year and – once more and regardless of the outcome – will prompt the IOC to try to find other, less democratic, bidders.

Upside

These looming conflicts still offer some positive aspects. Cities, regions and countries involved in Olympic bids have seen greater use of citizen participation and this led to better-informed discussions about modern direct democracy.

In Hamburg, the democracy movement Mehr Demokratie (More Democracy) has criticised the plebiscitary approach to the Olympic vote and proposes more citizen-driven forms of public votes.

The 2014 referendum in Krakow, the first ever binding referendum at city level, was held with votes on other issues.

In several other capitals across the globe which are interested in hosting future games – for example Paris, Rome and Stockholm – it will be very hard to push ahead without involving the citizens.

Nevertheless, this frequent reference to active citizenship and participatory democracy will not reconcile the diverging dynamics of modern Olympics and modern democracy. What’s more, it is very hard to see who could come up with a solution.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the views of swissinfo.ch

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.