‘Revocation right as democracy’s security valve’

In Switzerland, the option exists to challenge a government that may disappoint. Very few citizens are aware of it, but in a few cantons citizens have the right to revoke an elected official, as political expert Uwe Serdült explains.

Ever since 1848, when Switzerland became the modern state, the right to recall elected cantonal institutions has existed.

In response to colleagues around the world who were curious about the phenomenon, Serdült, Research Collaborator at the Center for Democracy Aarau, published an article entitled “The history of a dormant institution: Legal norms and the practice of recall in Switzerland”.

swissinfo.ch: People elsewhere in the world would dream about a citizen’s tool to recall governments, yet in Switzerland, the existing instrument is hardly ever used. Why is that so?

Uwe Serdült: It is a means of last resort that can be applied when all other control mechanisms fail.

Revoking governing bodies by citizens began between the middle and end of the 19th century, in other words during the formation of the modern nation state, when Switzerland became the organised and peaceful country that we know today.

After the right was introduced, other mechanisms followed, such as the referendum and the people’s initiative, which allowed a law to be stricken or to introduce a constitutional amendment, without having to dissolve a government or parliament.

The efficiency of the justice system and various tools for accountability in public institutions were then added.

In Switzerland today, cases involving politicians’ incompetence or corruption are resolved mainly through legal means, media pressure or internal reorganisation.

swissinfo.ch: How is the right to revoke implemented in Switzerland and how often has the tool been employed?

U.S.: The right does not exist at federal level. Only six out of the 26 cantons regulate it. These are Bern, Schaffhausen, Solothurn, Thurgau, Uri and Ticino. Uri and Ticino also offers the right of revocation at municipal levels.

A minimum number of signatures is required –between 2% and 30% of the electorate – to lead to the removal of a parliament or the government, or both, without identifying precise individuals, thus distinguishing the process from those in other countries.

If a majority of votes is achieved, the public body is dissolved and new members are elected, with mandates lasting until regular elections are called.

There have only been a dozen attempts to activate the mechanism. Four times it came to a vote and only once, in 1862 it was accepted, in the canton of Aargau.

Switzerland was one of the first countries to recognise the right to revoke a mandate.

Today the right exists, according to different rules in several other countries, including the US, Germany, Poland, Peru, Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, Argentina and Venezuela.

The six Swiss cantons, which provide for this tool of direct democracy are:

Bern, since 1846, for government and parliament.

Solothurn, since 1869, for government and parliament.

Schaffhausen: since 1876 for government and parliament.

Ticino: since 1892, for cantonal government and since 2011 for municipal governments.

Uri, since 1915 for all cantonal and municipal elected bodies.

Aargau (1852-1980), Basel Country (1863-1984) and Lucerne (1975-2007) abolished the right.

At the national level, however, the popular election and revocation of the government do not exist.

Since 1900, several people’s initiatives have unsuccessfully sought to allow for the election of the national government. The most recent, in 2013, promoted by the Swiss People’s Party, was rejected by 76% of the electorate.

The most recent examples occurred in Ticino, where the recall process was limited to the government, including once at cantonal level in 2008 and in 2011 at the municipal level (in Bellinzona).

swissinfo.ch: The only successful recall vote in Switzerland occurred 154 years ago and dealt with an anti-Semitic issue.

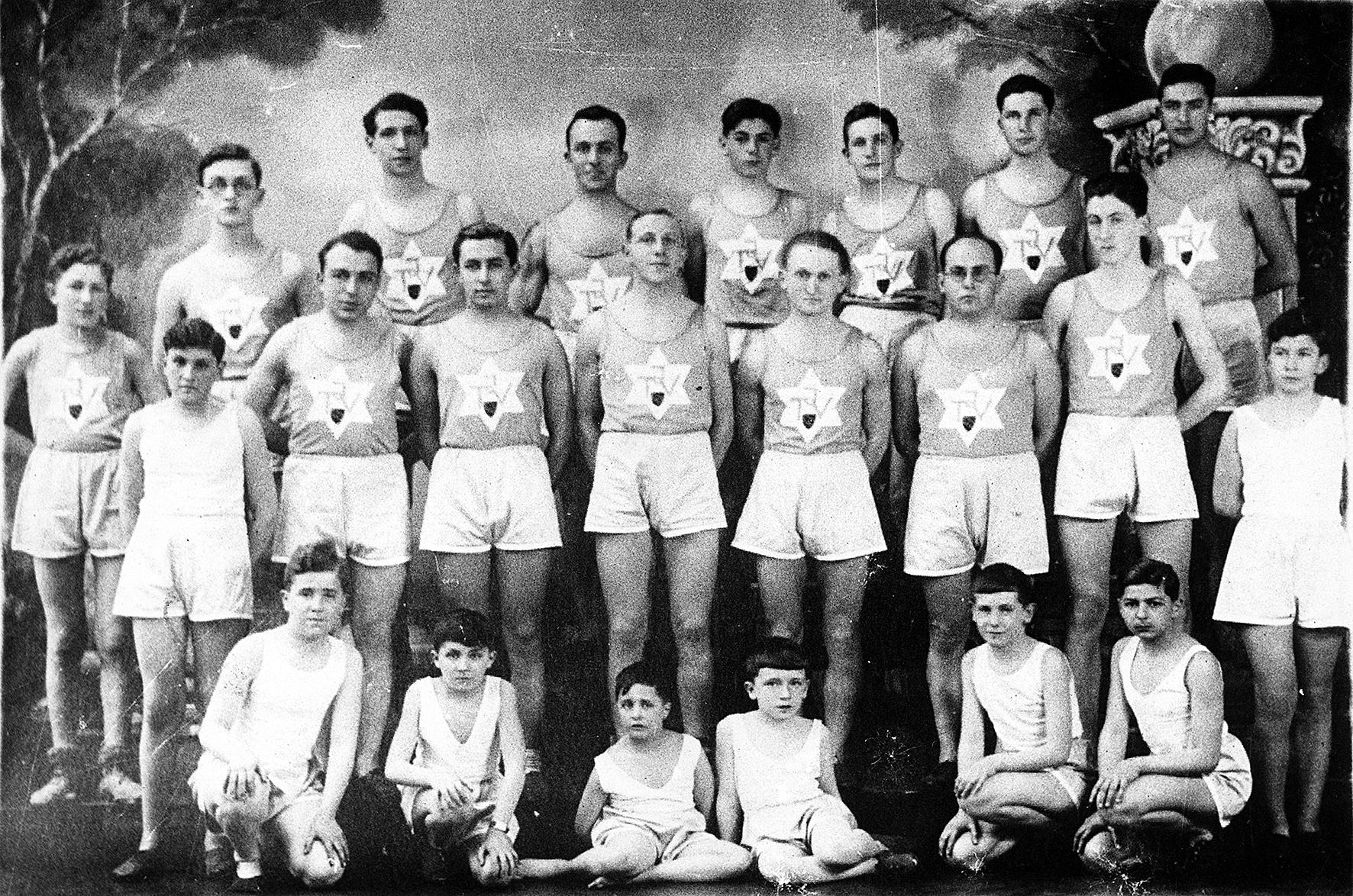

U.S.: Yes. Aargau’s parliament, which was liberal and Protestant, wanted to grant land legally to allow for the emancipation of Jews, who had only been allowed to settle in two poor, rural Catholic villages within the canton, in Endingen and Lengnau.

Several Catholic leaders, together with a few Protestant groups, launched a protest movement. Jewish homes were attacked and the revocation right was invoked.

They had to collect 6,000 signatures. They obtained 9,000 in less than one month, and in July 1862, 63% of votes supported the termination of the parliament’s mandate. The government resigned and called new elections.

swissinfo.ch: The revocation allowed a profound popular malaise to be put on trial amid a budding democratic process.

U.S.: It is important to remember that the tool was used when memories of serious conflicts between Catholics and Protestants were still fresh. Unlike the situation before 1848, these opposing forces now clashed on an institutional level, and no longer on a battlefield.

For a long time, there had been revolutions and radical changes, and the time had come to organise modern Switzerland.

A few cantons had openly suggested that the right to revoke mandates be set up to avoid revolutions. It was a justification to avoid violence. The revocation right could be a security valve to channel popular discontent via a political institution, and within a political process.

swissinfo.ch: Is the revocation right disappearing within the Swiss context?

U.S.: The historic trend appears to be so. Only six out of the nine cantons that originally adopted it still maintain the right. In the canton of Ticino, with three failed attempts to revoke officials, and where the political elite sometimes becomes involved in fierce political disputes, the mechanism was extended to municipal levels.

It appears that there still is a need to maintain the institution, especially on a local scale. Certain recent scandals have shown that some citizens are demanding the mechanism in cantons that do not have it.

SWI: Have these demands had an impact?

U. S.: The revocation process in Switzerland is aimed at an entire executive body which, as a rule, has between five and seven members. But there is now a greater tendency to call for an individual destitution mechanism, especially in the case of cantonal governments.

This is the case of Geneva. A scandal that affected the trust placed in a member of the cantonal government led the canton to adopt a constitutional reform in 2021, that provides for the possibility of dismissing one of the seven members of its collective government as of June 2023.

At least 40 members of the cantonal legislature must agree to the removal. If more than two-thirds of the parliament are in favour, the proposal will be submitted to a mandatory referendum. In other words, the legislature leaves the final decision to the citizens at the ballot box.

The canton of Aargau will also decide in May 2022 to allow the destitution of a single member of the cantonal authority as opposed to the whole body.

swissinfo.ch: Given difficulties in the national parliament in recent years, for political parties to agree upon the composition of the seven-member cabinet, wouldn’t it make sense that citizens elect the government directly or revoke it?

U.S.: There already have been unsuccessful people’s initiatives to allow citizens – and not parliament – to elect the government.

Theoretically, it could be possible that an initiative demand the right the revoke the mandate of the cabinet, even if the election of the government by the parliament is maintained.

Nonetheless, I do not believe that such a proposal would be backed in a vote.

From the 17th century, Jews could settle permanently only in Endingen and Lengnau, in canton Aargau.

On 1 July 1862, the canton proclaimed Jewish emancipation. But opponents employed two democratic tools to impede the change – revocation and a complicated version of optional referendum against the emancipation law – both of which were supported by Aargau’s citizens. The result lead to less rigour in limitations and no equality of rights.

But on 14 January 1866, Switzerland accepted the freedom of settlement for Jews (with 53.2% of votes in favour of the change) in a partial revision of the 1848 constitution.

With our consensus-style politics – aimed at respecting linguistic and cultural diversity, as well as maintaining a balance between interests in urban and rural areas – I do not know if it would be right to leave the election, or revocation of the government, in the hands of the citizens.

I think that this could provoke a major polarisation, or open cultural breaches that do not exist today.

Personally, I am opposed to it. The competence belongs to the parliament.

swissinfo.ch: Why is it interesting to discuss the revocation right in Switzerland?

U.S.: A number of political experts elsewhere – such as in Peru, where thousands of elected authorities have been revoked – asked us how it worked in Switzerland.

We then published the book entitled “The dose towards poison”, on the situation in Latin America, the United States and Switzerland.

The issue is of importance in other countries, such as Ecuador and Venezuela.

(This interview, translated from Spanish by Paula Dupraz-Dobias, was published in English in 2016 and updated in 2022)

Translated from Spanish Paula Dupraz-Dobias

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.