The powerful case for ocean democracy

The oceans of the worlds are at risk as never before. Although taking action remains difficult via our land-based governance systems, there are some promising starting points for what could be called “ocean democracy”.

“Welcome to paradise!”

That frank greeting from Dave, the lifeguard on Low Island, is more than appropriate. Discovered and named by Captain James Cook in 1770 on his first trip to the Southern Pacific, this very small island of just two hectares is home to a strategic lighthouse. It was also the first place in the world where scientific studies were conducted about coral reefs, back in 1928.

“We are here in the middle of a fantastic world,” says Dave, who has been welcoming visitors to the 5,000-year-old coral island for many years. But, he cautions that “this world is acutely threatened”.

In just two years, climate change-related events – including so-called mass bleaching – have killed up to half of all the coral animals External linkthat composed the 2000-kilometre-long Great Barrier Reef outside Northern Queensland in Australia.

Additionally, the millions of tonnes of plastic bags which find their way into the world’s oceans every year are killing many marine mammals and reptiles including the majestic sea turtles.

“Our turtles here at Low Island can become as old as 150 years, but many die nowadays after having met a plastic bag in the sea,” says Dave, whose beautiful island – which has become home to 50 different bird species as well – may disappear in the not-so-distant future if sea levels rise a few metres.

Paradise lost?

So paradise may soon cease to exist if the world fails to address key challenges, which do not know clear local, regional or national borders.

But efforts have been made to develop some form of sea governance structure. In 1958, the International Maritime Organization External linkwas established to better regulate maritime safety and liabilities linked to pollution. A quarter of a century later, the United Nations ratified the convention on the Law of the SeaExternal link, leading to the establishment of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea in 1996 in Hamburg, Germany.

But this global legal structure is often overlooked by both state and non-state actors, leaving it without the legal legitimacy to protect the oceans. Instead, the seas are still handled as “unclaimed territories”, up for power grabs. Recent examples include the efforts by China to extend its sovereignty in the South China Sea by creating artificial islands.

While all of this is bad news for the billions of animals in the oceans, citizen-driven actions have surfaced in growing numbers. At a gathering in Portland, Oregon, last May, I met Mitsue Cook from the Seattle-based Healthy Oceans Network External link.

“Our mission is to empower people to take care of the ocean,” said Cook, who has roots both in Japan and Hawaii.

Ocean democracy, by its nature, must establish broad and global networks to make a tangible difference. In the beginning of December, a “Sustainable Ocean Summit”External link took place in Halifax, Canada – one of the upcoming stops on the #ddworldtour – and gathered leaders from ocean-based industries from around the world.

Citizens of the Great Barrier Reef

A day before I visited Low Island and the Great Barrier Reef, I strolled along the beautiful Ocean Esplanade in Cairns, Northern Queensland, only to discover another promising Ocean democracy initiative: the Citizens of the Great Barrier ReefExternal link.

“This is also a symbol of diversity and resilience,” says Som Meaden, one of the local promoters of the initiative.

In a lively exchange at a park table – a few metres from the fascinating sculpture “Citizens’ Gateway” created by local artist Brian Robinson – Meaden explains that his newly established organisation offers people from across the globe the chance to become “active citizens” of the Great Barrier Reef.

“We invite everybody to engage in different actions to support and help the reef,” says Meaden, who is a technology expert in charge of the websiteExternal link for this global citizenship project.

Born and raised here in Cairns, the 35-year-old new father of a one-month-old daughter knows very well that online-based friendly commitments by a few thousand individuals will not make the reef and other ocean populations survive in the long-term.

“Ocean democracy also needs a lot of land-based initiatives,” he says.

That’s because the oceans and the Great Barrier Reef are threatened not merely by pollution from passing ships but also by on-land industries like agriculture and mining, and the run-off they produce. That reality should make the oceans a bigger issue in Queensland, the Northeastern Australian megastate of more than 1.8 million square kilometres home to five million people where agriculture and mining are major economic drivers.

In the recent Queensland state election – which for the first time in Australian history gave a second term to a female Prime Minister, the Labor Party’s Annastacia Palaszczuk – a controversial plan by Indian billionaire Gautam Adani to start an enormous coal mine created a big public debate about sustainable governance and economy. Just before the hard-fought election, Prime Minister Palaszczuk announced that her government would veto a federal loan of more than one billion Australian dollars to connect the new mine by rail with the Queensland harbour town of Townsville.

Historically, there has been little lobbying for offshore territories like our oceans. But threats posed by onshore developments like the Adani mining projectExternal link, such as the large ships transporting coal or climate change resulting from coal energy use and production, make a powerful case for a new type of people power: ocean democracy.

Swiss-Swedish author and journalist Bruno Kaufmann is on a world tour to explore the state of democracy visiting more than 20 countries on four continents until May 2018.

swissinfo.ch publishes a weekly Notebook and multimedia reports by Kaufmann over the next few months as part of its coverage of direct democracy issues.

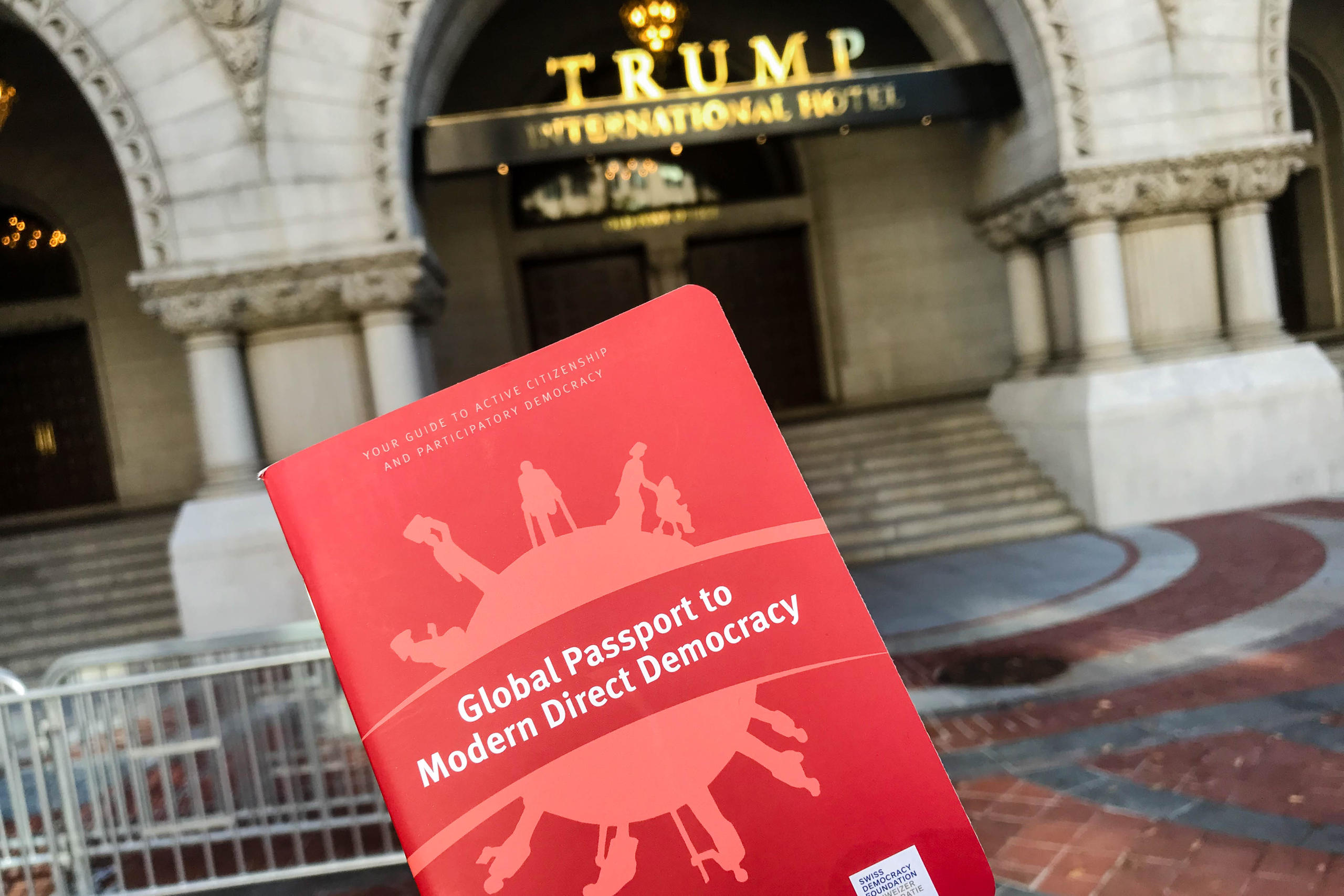

Kaufmann’s democracy world tour is mainly sponsored by the Swiss Democracy FoundationExternal link, where he is the director of international cooperation. The Swiss Democracy Foundation hosts various projects and platforms linked to participatory and direct democracy across the globe, including Democracy InternationalExternal link, the Direct Democracy NavigatorExternal link and the Initiative and Referendum Institute EuropeExternal link.

#ddworldtour Notebook. Follow the tour on #ddworldtour @kaufmannbruno @democracyreporter and /people2power.info

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.