The fast-track school term in an asylum centre

Children at a Zurich asylum centre don’t pack their rucksacks and head off to the local school each day like other kids – they’re taught in a rented space, turned into a classroom just for asylum seekers, while their family waits for a decision on their future.

“Bär, Bärrrrr.” Three children sit cross-legged on the floor of a classroom, looking at a picture of a bear with their teacher. Although they are learning how to say the German word for the animal, their mother-tongue is Arabic.

These children could spend almost five months attending the special classes held near the Juch asylum centre, on an industrial estate on the outskirts of Zurich.

The pupils are part of a trial fast-track asylum process that has been running in Zurich since January 2014. The aim is to process straightforward applications within 140 days.

The test project will run until September 2015. If it is judged to be a success it could be used to help the government cut processing times nationwide.

The goal for the children at this particular centre is to try and keep up with their education and get used to being in a Swiss classroom, in case their parents’ application is accepted.

“They haven’t all been to school before, they can’t all write and some are six- or seven-years old already. They do have to slowly get started,” Gynna Zuberbühler, one of the centre’s two teachers, told swissinfo.ch as she leafed through an animal picture book with the younger group of the current students.

“German is definitely the priority…lots is learnt through play with the little ones, but there are also simple writing exercises.”

In January a government pilot project was started to see if the time taken to process asylum applications could be slashed. So long as cases are handled thoroughly and fairly, general opinion in the field is that it is better for asylum seekers and their host countries if the time taken is as short as possible.

The aim is to process cases within 140 days or nearly five months. To help this process, asylum seekers are given free legal advice, to assist them in getting their case folder in order and obtaining the required evidence and documentation.

Five months into the pilot project, at the start of June, the government gave an assessment of progress so far. More cases had been handled than expected: 669 cases began the faster procedure and decisions were taken in 319 of them. Asylum was granted to 44 of the cases.

To put those numbers into context – the Swiss authorities received 21,465 applications in 2013, according to the Federal Migration Office.

The test project will run until September 2015.

As the length of time their parents will wait for a decision is short in the context of a school year, Switzerland is trialling teaching the children purely within the Juch centre, and not enrolling them in local schools.

Classes which keep the children solely within an asylum centre have been going on since the 1990s, but are relatively rare.

They have to attend classes somehow, as the UN Convention on the rights of the child sets out that all children have the right to education.

“The children’s access to education might have been disrupted if they have been on the road for a while, if they have been in a country at war, like Syria at the moment,” Hélène Soupios-David, project officer at the European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE) told swissinfo.ch.

“It’s quite important for their personal development that they can have access to education again as soon as possible,” she adds.

A class of their own

According to Markus Truniger, head of intercultural educational science for elementary schools in canton Zurich, the children receive the same schooling as any other non-German speaking child in a local school.

“They have 28 hours of lessons a week – that’s the regular amount, the same as all other children” Truniger told swissinfo.ch

Zuberbühler says that the children are happy to come to their makeshift school. “Some like it because of the regular structure that it gives them and some like it because we get to go on trips outside into the countryside. And the classroom is really their space, not their parents’.”

“There is no normal,” Zuberbühler adds, explaining that every day is different due to the “wide-ranging cultural differences” and the frequently changing class members. The pupils are always split into two groups by age and the class has a basic schedule to keep, with set activities on each day, such as a visit to the library on a Friday morning.

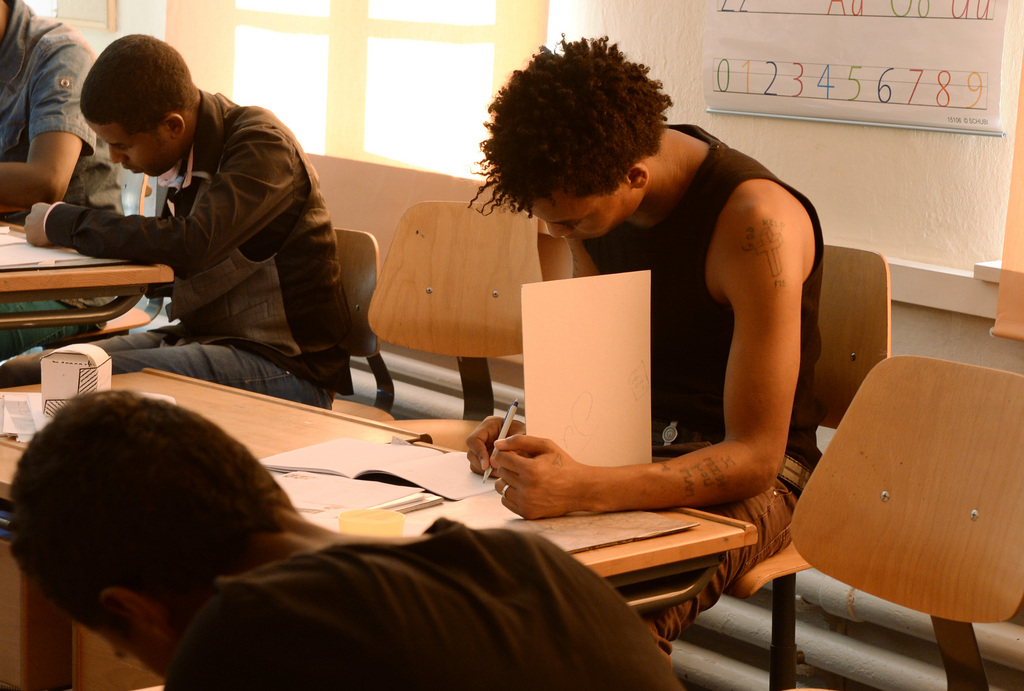

In the next classroom along in the two-room school, another teacher addresses a group of teenagers in German.

There’s a notable difference between the smiling faces of the younger pupils, loudly sounding out their first German words and the older students, diving seemingly reluctantly, and quietly, into German grammar.

More

Fast track system to soothe asylum tensions

They watch as the teacher points out different verb forms on a white board and then tells them to write their own sentences in their notebooks. She uses hand signals when her words are met with uncertain looks.

Children of asylum seekers normally attend a local school in canton Zurich. But when there are enough children at one centre, a class could be set up within its walls as it can be difficult to fit them in to a local school.

However in other parts of the country, some schools have objected to having these children in their classes, mainly due to their lack of Swiss national language skills.

“We normally decide on a case by case basis,” explained Truniger. “It’s difficult to integrate them into a school when the rotation is so high.”

Closed-classes

The issue of where to educate children who may only be in Switzerland for a short amount of time, is one that causes some differing views.

“In Switzerland there is debate as to whether children should be integrated at school as early as possible. Many specialists say that this is best, but [the pilot project] is a different model,” Claudio Bolzman, professor in sociology at the University of Applied Sciences Western Switzerland and the University of Geneva, told swissinfo.ch

Bolzman said not sending these children to local schools was “contradictory with the general politics of integration that authorities want to develop for children of migrants, especially if they may stay here for a long time”.

But the use of such closed-classes to acclimatise children can be beneficial and even recommended at first.

“If you have a child who has never or rarely been to school then it might take some time for the re-adaptation, you cannot just throw them into the normal school system where they will not understand anything,” said Soupios-David.

“If it’s in the context of getting them ready or teaching them German that would be OK, but I would say as soon as possible, try and put them in the national system.”

Preparing teachers

Moving to a new country, leaving behind their home and friends, and getting used to a new country can be the least of these children’s problems. “Asylum-seeking children will have suffered trauma, either back home or along the way,” said Soupios-David.

The Juch asylum centre has psychologists to help with these issues outside the classroom. Many of the refugees will have come from countries such as Eritrea or Somalia, they will have travelled for weeks in dangerous conditions, slept in crowded rooms, struggled for food and left behind anything from poverty to the effects of civil war and repression.

“The teachers are not trained therapists, they can’t be both, that’s not their job. They have to offer a child-friendly environment and give them the opportunity to learn,” said Truniger.

The focus in class is mostly on teaching German. Teachers have to have the teaching German as a foreign language qualification, which covers a number of issues relevant to teaching non-native speakers though.

“Part of the course is understanding the many differences between the language-learners; how to respect and recognise issues that concern intercultural learning and how to develop courses that end in self-empowerment,” Jörg Keller, head of the German as a Foreign Language department at the Zurich University of Applied Sciences, told swissinfo.ch.

Like similar courses at other institutions, there is no specific focus on asylum seekers.

Truniger, admits it would be advantageous for teachers to have an “overview” of the psychological issues the asylum-seeking children might be dealing with, in order to work better with them.

“During the Kosovo war we ran certain courses along these lines, but not at the moment.”

Right now, every day in the asylum centre’s classrooms is different, children come and go and the school’s toys and picture books pass through different hands.

What do you think about the pilot project? You can contact the author of this article, Jo Fahy, on FacebookExternal link or on TwitterExternal link.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.