Promoting integrity without transparency

As the Qatari-backed International Centre for Sports Security (ICSS) came under increased scrutiny for its links to Qatar, its founder and president, Mohammed Hanzab, launched another initiative in 2016: the Sports Integrity Global Alliance (SIGA). But the organisation ran into the same issues as ICSS: a lack of transparency and international credibility.

The launch, SIGA saidExternal link, came in reaction to “calls from stakeholders across all corners of industry involved in and supporting sport, for the establishment of a global, independent and neutral sport integrity body.” Hanzab became the new group’s vice-president.

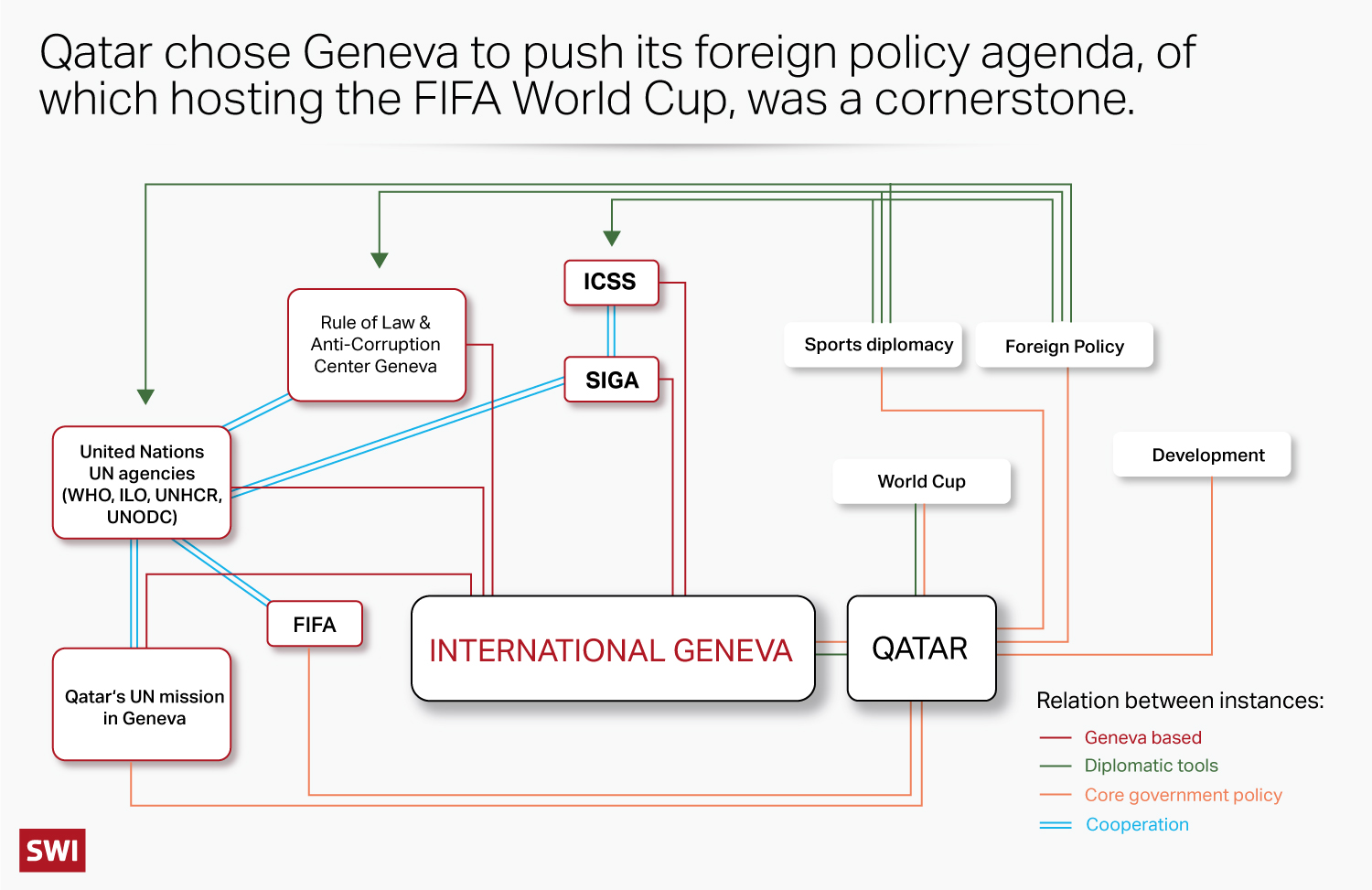

Qatar’s Geneva offensive

This is the third part of a three-part series about how Qatar has used Switzerland as a hub for efforts to boost its public image since being named host of the 2022 World Cup. In Part 1, we looked at the networks and influence built up by the emirate in Geneva, while Part 2 reported on the International Centre for Sports Security (ICSS) – a Qatar-founded, Geneva-based institution faced with accusations of lacking transparency.

Just like ICSS, SIGA sought to gain recognition and support from well-respected international organisations, companies and experts.

One of them was the Basel Institute on Governance, an anti-corruption organisation. Mark Pieth, one of the institute’s founders and a well-known anti-corruption expert, had been previously tasked with overseeing a reform process at FIFA, football’s world governing body.

The new sports group promptly claimed that the Swiss organisation was a firm supporter.

Gemma Aiolfi, head of compliance and corporate governance for the Basel Institute, responding to questions, wrote in an email to SWI swissinfo.ch that the institute had initially been drawn to SIGA for its core purpose.

“The ambition of SIGA therefore was one that we supported along with many others,” she says, pointing to a general lack of standards for integrity and ethics in sports. “SIGA approached us because of our expertise and experience in the field of governance and anti-corruption, and relative in-depth insight into certain aspects of governance and sports.”

SIGA also attracted politicians such as Emanuel Macedo de Medeiros, from the Portuguese archipelago of the Azores who, under the leadership of former prime minister José Manuel Baroso, assumed the leadership of the socialist party for the district of Porto. Previously affiliated with ICSS, Medeiros became SIGA’s CEO. He was re-elected to the post unanimously earlier this year.

Katie Simmonds, a British sports lawyer, followed a similar path, first joining ICSS as head of governance and financial integrity, before becoming a “co-founder” and later Chief Operating Officer of SIGA.

As Qatar embarked on making the 2022 World Cup bid a reality, reports of abuses and deaths of migrant workers building the infrastructure became a growing liability to the upbeat narrative the gas-rich country was eager to project. WorkersExternal link from impoverished communities in south and east Asia were often denied wages, forbidden from changing jobs, and unable to freely leave the country. Some foreign workers also faced harsh punishment for criticising the system.

A 2021 investigation by The GuardianExternal link newspaper found that at least 6,700 migrant workers died in Qatar between 2010 and 2020, as the country readied itself for the sporting event. However, it is unclear how many of these workers were employed on World Cup construction projects. Qatari authorities say that 37 workers have died while working on tournament building sites, with only three of these deaths resulting from a work accident. For its part, the Geneva-based International Labour Organization (ILO) conducted what it calls an “in-depth analysis”External link of work-related deaths in Qatar and concluded that 50 workers died in 2020, over 500 were seriously injured, and 37,600 suffered mild injuries – and all mainly in the construction industry.

Under pressure in particular from the Geneva-based International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) and the ILO, Qatar announced labour reform commitments seven years after winning the bid, including banning midday outdoor work during summer months, allowing workers to leave Qatar without employer permission, and establishing a minimum wage.

But advocacy group Human Rights WatchExternal link said these measures have been “woefully inadequate and poorly enforced”.

Corruption investigations into the bidding process also got under way. In late 2021 the United States Department of Justice saidExternal link a number of FIFA officials had received bribes to vote for Qatar in 2010.

And in France investigations are ongoing into a meeting between former president Nicolas Sarkozy, the former president of the European football federation UEFA, Michel Platini, and the Qatari emir days before the successful bid. The allegation is that economic benefits were obtained in exchange for a French vote. No charges have been filed.

Less than a month before the World Cup kickoff, Tamim Bin Hamad Al-Thani, the emir of Qatar, described the event as a “major humanitarian occasion” in a speech to the Shura council, the legislative body. He condemned criticisms of Qatar as “fabrications”.

“They [SIGA officials] realised that they had to create the impression that they were for sports integrity and were not dependent on Qatar,” says Jens Sejer Andersen, director of Play the Game, a Danish-backed initiative to raise ethical standards, democracy and transparency in sports.

For Andersen, the new sports organisation presented more of the same as had been observed at ICSS.

SIGA, he says, has been “very good at holding fine speeches and organising prestigious events, gathering high-ranking people and focusing on all those sports integrity issues that have nothing to do with Qatar.”

SIGA in action

“SIGA is part of a collective effort to usher the industry into a new era, where governance and integrity are at the top and where all organisations and champions got together to join a vision that is collaborative, positive, and aiming for meaningful reforms,” Medeiros told SWI swissinfo.ch.

He says the association developed an “independent rating system to ensure a level of compliance by sports organisations regarding standards”.

But for now, the number of organisations that have been rated is limited and details on how evaluations are done are scarce. Last year, the European Rugby League announcedExternal link that it had achieved a near-perfect compliance note according to the SIGA rating system, falling 2.5 percentage points short of full compliance due to weaknesses on diversity and unlimited terms for directors.

Match-fixing also became the focus of many of SIGA’s discussions, similarly to ICSS. Issues such as corruption at FIFAExternal link or controversies over Qatar’s World Cup bid, on the other hand, failed to warrant much discussion at SIGA, according to Andy Brown, a freelance journalist who has investigated both organisations.

Brown, who contributed to a short-lived ICSS journal in 2014, told SWI swissinfo.ch that SIGA reports on match-fixing incidents were shared with national associations before they were made public.

“The mission of SIGA and the ICSS seems to be to alert sporting federations of an issue before it becomes public knowledge,” he says. “They always have the same message.”

“‘It is time to stop match-fixing – it ruins sport’. They say this over and over again, but they never really seem to do anything,” he adds. “Nothing ever gets done.”

A week-long conferenceExternal link held in mid-September in Portugal demonstrated how the organisation operates. A sprinkling of officials from various sports organisations, including many from Portugal, along with several athletes discussed women’s leadership, security and safeguarding children in sports. Statements on commitments to integrity in sports were made by participants, many of whom received achievement awards from SIGA.

Hanzab, who gave a keynote speech, retweetedExternal link from the seaside conference venue that a UN office, the Division for Social Policy and Development, would be signing a cooperation agreement with SIGA. Meanwhile, European Football Federation president Aleksander Čeferin, also in attendance, lauded UEFA as a “trailblazer” in sports integrity. His predecessor at UEFA, Michel Platini, was given CHF2 million ($2 million) by Blatter as payment for consultancy work. Last July a Swiss court acquitted both men on criminal charges over the payment. In October Swiss federal prosecutors filed an appeal to overturn the acquittals.

Javier Tebas, president of the Spanish football league, who has long been critical of Qatari-funded football team Paris Saint-Germain (PSG), spoke at the eventExternal link, condemning states’ injection of money into sports, and offered the example of the Saudi-sponsored LIV golf tournament. He also brought up Nasser Al-Khelaifi’s conflict of interest as both PSG president and president of the European Club Association, an independent body directly representing football clubs across Europe.

Funding and accountability

Just like ICSS, SIGA lacks financial transparency and employs a dubious address. Its website lists a location in Geneva, Rue de la Croix d’Or 17A, the site of a building that houses a number of asset management firms but no sign of the organisation.

The most recent financial statements published on the SIGA websiteExternal link and validated by the Geneva accounting firm OC Révision Sàrl show that the group’s 2020 income was just under CHF660,000 ($670,000), coming mostly from membership fees. Contributions from individual members, however, have not been published since 2018, when numbers on various parts of the organisation’s website did not add up. Only GBP434,000 (CHF 566,370, according to the 2018 exchange rate) in membership fees were listed under a section entitled “Membership Paid” that purportedly shows payments from individual members. But in its declared income statement, CHF679,000 is given for total membership fees.

Administrative expenses, meanwhile, have remained rather stable in recent years, according to the SIGA website. In 2020, salaries for the entire year were listed at CHF1,286, plus unspecified consulting fees reported at CHF171,133. In 2019, before the pandemic, those combined expenses amounted to CHF220,078.

When asked about his own pay status, given the absence of any notable salary expenses in the statements, Medeiros told SWI swissinfo.ch: “I am not an employee of any organisation. I may render services occasionally – that is my purpose.”

OC Révision said it was unable to respond to questions about the financial statements it prepared on behalf of SIGA.

According to the SIGA website, in 2018 SIGA’s largest financial contributors were Qatar Airways, ICSS Insight, a non-profit outfit associated with ICSS, and MastercardExternal link, each having reportedly donated GBP70,000 (CHF76,644).

Since 2010, amid the emirate’s wider push to become a global force in international sports, state-owned Qatar Airways has become an official sponsor of top international football teams, including PSG. Its 2022 multimillion-dollar shirt sponsorship for the team came two years after the government bailed the airline out, following pandemic-related losses. In 2013, Qatar’s sovereign wealth-fund support of FC Barcelona was replaced by another multimillion-dollar sponsorship by the airline, before fans urged the club to ditch the deal amid ongoing allegations of workers’ rights abuses connected to the 2022 World Cup.

Mastercard senior vice-president for global sponsorship, Michael Robichaud, was given a SIGA awardExternal link on international women’s day this year for his services to sports integrity. He refused to comment to SWI swissinfo.ch about Mastercard’s association with SIGA.

“We have supported the organisation,” Jim Issokson, a communications representative for the company confirmed in an email, adding that Mastercard does not disclose details of the sponsorship.

SIGA’s platform claims the Basel Institute on GovernanceExternal link contributed GBP4,000 in 2017 and 2018, the last year that individual donations were published.

But the Basel Institute tells a different story.

Aiolfi, head of compliance and corporate governance for the non-profit, told SWI swissinfo.ch that only one payment of CHF4,000 was made to SIGA in 2017.

After the institute offered support in developing policies and governance documentation in 2017 and early 2018, Aiolfi says SIGA planned “to diversify its funding sources”. However, she says she does not know if the plan ever materialised.

The institute’s pro bono work ended in 2018. “We have had barely any relationship with SIGA since expressing our support when the organisation was created,” Aiolfi writes.

According to SIGA’s website, “members and committed supporters” include specific officials from academic centres, European sports associations, media organisations, groups promoting integrity and ethics in society, and several Portuguese sports federations, foundations and official institutions.

“They have a history of being inaccurate and exaggerating,” Andersen says of the support SIGA claims to receive from third parties. He also says that while the organisation claims to rally for greater integrity, it was lacking in transparency. “The financial information is simply not transparent enough and the figures seem unrealistically low when compared to the luxurious offices and conference venues they use.”

But like many other international sports associations, SIGA’s registration in Switzerland as an easy-to-set-up non-profit association comes with no obligation to keep financial accounts or publish them.

Medeiros denied that Switzerland’s regulations had anything to do with the choice of its base. “We were not moved by any artificial factors,” he says. “Our governance is not dictated by the law of the land. We go way beyond what Switzerland imposes.”

He cites internal governance codes, SIGA’s registration in the European Union’s transparency registry, and “audited, publicly-approved financial statements.”

Critics see ICSS and its spin-off SIGA as part of Qatar’s diplomatic strategy to make sports and the fight for greater transparency on its own terms as a key part of its global influence.

Anti-corruption expert Pieth says that SIGA’s ties to Qatar became quickly apparent to him after he was invited to attend one of their meetings.

“Qatar is a dangerous place,” he says. “I would not want to get anywhere close.”

“Qatar is as entitled as any country to invest in sports ethics and to promote integrity in sport,” says Andersen. “But what you cannot buy with investments is credibility. Credibility is in the mind of the beholder.”

Can you buy a reputation?

With the World Cup just around the corner, pulling off credibility has been a hard sell for Qatar. Today just as many questions remain about its human rights record and how it was awarded the World Cup as there were a decade ago. SIGA and ICSS’ ties to the emirate have tarnished their reputation.

In 2018, the French independent media site MediapartExternal link analysed documents obtained in the Football LeaksExternal link investigation project and concluded that in Lausanne, ICSS had spied on a Kuwaiti sheikh who was an influential figure in Asian sport. Mediapart also alleged that the group failed to alert international authorities when suspicions arose regarding possible match-fixing during a Qatar-North Korea match in 2014.

Multiple media and government investigationsExternal link have reported Qatari links to financial support for Hamas, the Palestinian group designated by many countries as a terrorist group; ISIS; Al-Qaeda, including in Libya and Yemen; and the al-Nusra Front in Syria. Qatar has denied supporting terrorism.

Meanwhile Qatari efforts to silence critics are reported to have continued. Earlier this year, the Associated Press revealedExternal link that a covert Qatari operation involving a former CIA officer had targeted the head of the German football association, Theo Zwanziger, a critic of Qatar’s FIFA bid, to follow him and silence him – unsuccessfully – through spyware.

Andy Brown, a journalist who had freelanced for ICSS, says he too had been “tailed by two people” in January 2016 when he was invited by the organisation to report on a conference at the British parliament. He alleges the pair had been ordered to follow him after he began an investigation for an independent media publication on the relationships between SIGA and its sponsors, particularly with regard to Qatar.

“Whitewashing is a serious concern specifically when states have wealth, possibly from fossil fuels, to use sporting events to distract from serious rights records,” says Michael Page, Human Rights Watch deputy director for the Middle East and North Africa. He calls the phenomenon a “major Gulf issue.”

“That is a serious concern, particularly regarding this FIFA World Cup,” he adds.

But Page says FIFA is also to blame for the situation: “In Qatar’s case, they got this event [World Cup] through controversial means and from a human rights perspective the body that attributed them the event gave no conditionality on any of the rights abuses, which is why we are in this predicament.”

In March, two months after announcing he had moved to Qatar, FIFA president Gianni Infantino downplayed the deaths of migrant workers, saying the workers feel “dignity and pride” in tough conditions.

Qatar’s ambassador to the UN in Geneva told SWI swissinfo.ch in early September that the country’s support for ICSS and other sports integrity ventures was part of its diplomatic effort to promote human rights and peace.

“The State of Qatar spares no efforts in funding initiatives, including the ICSS, to empower young people through sport,” a spokesperson for the diplomat wrote in an email.

Edited by Virginie Mangin/gw

This article was amended on November 17 to provide additional information on the number of migrant workers thought to have died in Qatar.

More

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.