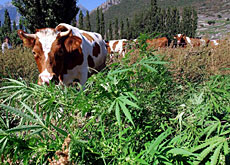

Alpine air leaves dairy cows gasping

Too much fresh air can be a bad thing, especially if you're a cow grazing on alpine pastures – but the cheese made from this milk is healthier for humans.

That is the conclusion of research by the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, which found that the cheese was packed with unsaturated fatty acids that can prevent heart disease.

Two herds of Brown Swiss cows were left to graze on the Weissenstein Alp, where the institute has a research station. Pastures there are 1,900-2,600 metres above sea level. A control herd of Brown Swiss cows was positioned on lowland 400 metres above sea level.

The researchers discovered that the higher the altitude the lower the milk yield. That the air was thinner at higher altitudes also had consequences for the animals, according to Michael Kreuzer, the professor who led the team.

“The altitude [meant that] the cows required additional energy but they were not able to eat more because the stomach has a certain filling capacity,” Kreuzer told swissinfo.

Something similar happens to humans above 3,000 metres – their sense of taste changes, which means they eat less and take in up to 40 per cent less energy.

To compensate for their loss of energy, the cows mobilised their own body reserves, such as fat and muscle proteins, leading to weight loss.

The milk’s protein content also decreased, meaning that any cheese made from it was not that firm.

Healthy acids

Kreuzer said the animals’ health did not suffer from the experiments.

“This was within the limits they could mobilise from body reserves, so none of the cows really got ill. It’s more the economic loss from less milk, which is not very good for the farmer,” he explained.

However, he conceded that the sooner these animals were taken up to higher pastures, the more time they would have to acclimatise.

“Actually the best thing is to put these cows on the Alps before they have their first calf, which means before they get milk for the first time. They get very robust and suffer less,” he said.

The Swiss Farmers’ Association (SFA) agreed that a period of acclimatisation was the best way forward.

“The animals have to be trained to deal with high altitudes, just like top athletes,” said Thomas Jäggi from the SFA’s economic section.

Upside

The upside, according to the study, was that the cheese produced from low-milk yields had more nutritional value for human consumers than those made from milk produced by cows grazing at lower altitudes.

“There was a higher concentration of desirable fatty acids, such as Omega-3 and conjugated linoleic acid, compared with lowland cows,” the professor said.

As to why, this was a question that the researchers were particularly interested in but one that had no easy answer.

The team first thought that alpine grass was high in fatty acids compared with lowland grass. This was not the case.

In the end, the researchers came closer to the bulls’ eye.

“The cows mobilised fats from their bodies and these fats already contained fatty acids; also alpine flora contain secondary plant constituents, which affect the rumen [first chamber of a cow’s digestive trait] fermentation in such a way that these fatty acids increase in concentration in the milk,” Kreuzer said.

The next stage of research will take a closer look at these results.

Clear advantage

For their part, alpine farmers will continue to take their cows to graze on higher pastures from May to September.

Jäggi explained that this was partly out of tradition and because the pastures were there to be exploited, meaning that farmers could use lower lying lands for other purposes.

“There is also the economic consideration – these farmers want to make alpine products. Alpine cheese, for example, is a delicacy and not a functional food,” Jäggi added.

The government also pays direct subsidies to farmers, who use and hence protect the alpine landscape in a sustainable manner.

“By grazing their cows or even sheep there, farmers are ensuring that Switzerland’s landscape continues to look the way it does,” Jäggi said.

swissinfo, Faryal Mirza

Cheese is Switzerland’s main dairy export, accounting for 61 per cent.

Total cheese production in 2004 was 162,397 tonnes.

The Swiss drink 80 litres of milk a year per head.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.