Alpine nimbyism freezes Swiss green energy dreams

High in the Swiss Alps, where even in mid-June there is snow, workers are installing photovoltaic panels across the face of Europe’s highest dam.

Switzerland has long basked in its reputation for clean energy: helped by abundant hydropower, less than 10 per cent of the electricity it produces emits greenhouse gases. Yet today, Switzerland’s complex regulatory process and local objections to potential eyesores means new green projects such as at the Muttsee reservoir have become an exception.

As a result, one of the world’s wealthiest and most environmentally conscious societies is in danger of moving backwards. Switzerland is also about to become more dependent on imported energy, just as it faces the growing risk it may decouple from the EU’s electricity grid thanks to an increasingly fractious diplomatic tussle with Brussels.

The government is committed to shutting down the country’s three nuclear plants over the next decade or so. When that happens, Switzerland will lose a third of its current energy generation, and no one is sure how the shortfall will be made up.

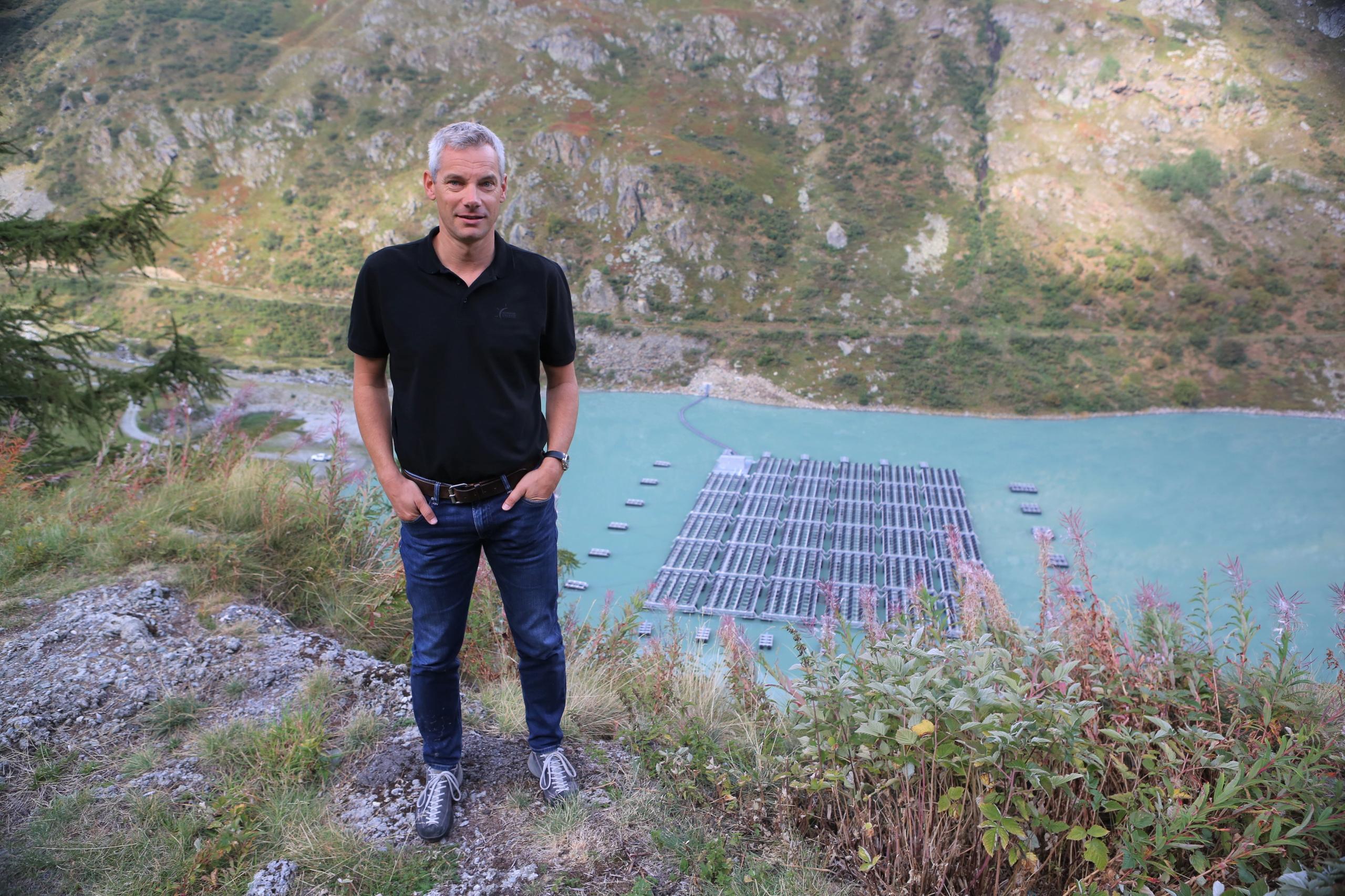

“The idea of the project was really to try and show what is feasible,” said Christian Heierli, project leader for power company Axpo at the Muttsee AlpinSolar project.

Axpo hopes the facility, built with 320 tonnes of material flown by helicopter to 2,500 metres above sea level, will showcase Switzerland’s solar potential.

“There are really only a very few large-scale [renewable] projects in Switzerland,” Heierli said. Getting permits to build solar and wind farms was almost impossible, he explained. “Apart from people installing PV panels on the roofs of their houses, not much else is happening.”

Bern recognises it has a problem. Last year, Switzerland produced just 311kWh of energy per resident from solar and wind power, according to the Swiss Energy Foundation, a renewable energy think-tank. By comparison, Denmark produced 3,027kWh, Germany 2,232kWh and the UK 1,304kWh.

The potential for new hydroelectric plants, which account for 58 per cent of supplies, is small with upgrades to existing facilities only increasing output by marginal amounts, experts warn.

At the same time, Switzerland last month rejected long-running negotiations with Brussels over a new framework agreement to codify their sprawling net of bilateral treaties.

As a result, last Thursday, the first of several treaties governing Swiss connections to the EU energy market lapsed. Although there is only a remote chance Switzerland will be cut off from the EU’s grid unless a permanent deal with Brussels is struck, the country risks higher energy costs and uncertain supplies.

That would be particularly burdensome since Switzerland’s energy production is seasonal: in winter months, as rivers freeze, it depends more on energy imports to meet demand.

“We just don’t know how electricity exchange will work with the EU in five or 10 years time,” said Christian Schaffner, director of the energy science centre at ETH Zurich and a former senior official in the Swiss federal energy department. “It’s a big uncertainty.”

More

In the Swiss Alps, solar power takes to the water

Bulking up on domestically produced, renewable energy might help. Both solar and wind work well in winter, thanks to Switzerland’s geography. At the Axpo Muttsee project, for example, solar panels will produce 50 per cent more electricity per square metre than in the valley below. Colder temperatures improve efficiency, the snow reflects light back on to the panels and the site is often above the cloud line. Such features are common to many potential sites.

Lots of potential

The country has the potential — in solar at least — to become a European leader. But without a more flexible regulatory environment, the opportunities for new projects are scant.

“The regulatory framework has to be fundamentally adjusted in order to increase the expansion of renewable energies,” said Guido Lichtensteiger, a spokesman for Alpiq, one of Switzerland’s biggest power companies.

Last month, Bern unveiled a package of proposed legislative changes to try and spark more renewable projects. For many, though, the proposals only tinkered with the problem and did little to properly address the country’s complex approval process, which is deeply rooted in Switzerland’s highly devolved political system.

A typical building project for a new power plant requires permission from Bern’s environmental and energy regulatory bodies, and then the same again from the government of the canton it is located in.

Communal building permissions are further required. As with all construction in Switzerland, a single individual can object. Legal wrangles can last years and are sometimes fought at great expense all the way to the Supreme Court.

More

Swiss among last to embrace wind and solar power

In October, the turbines finally began to turn on the Windpark Gotthardpass, one of Switzerland’s biggest renewable projects. But it took 18 years of negotiations to come to fruition.

In the 2017 national referendum to approve the government’s 2050 energy goals, Swiss voters strongly endorsed plans for more construction. Bern’s plans envisage building more than 850 wind turbines in the country over the next three decades. Currently, there are just 37.

But so far little has been achieved. Plans for four turbines in Kulmerau-Kirchleerau were recently scrapped after the local village rejected the proposals.

“Wealthy Switzerland is a stronghold of local opposition that is often explained as a federalist tradition,” wrote Zurich’s NZZ newspaper.

“A lot of the public [awareness] is not there,” added ETH’s Schaffner about the disconnect between Swiss support in principle on a national level and the local reality of new construction.

“[It] is interesting when you think . . . that we built all these dams in the Alps years ago, but now we don’t want to. You probably have to talk to a behavioural scientist to understand why that is.”

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2021

More

Swiss CO2 law defeated at the ballot box

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!