An anti-Jewish revolt in an enlightened country

For centuries, Jewish people living in what is now Switzerland faced discrimination. It took the fall of the old Helvetic Republic for equal rights to finally become a reality.

In the early hours of September 21, 1802, a mob of about 800 people attacked the Jewish communities of Lengnau and Endingen. The instigators harassed the inhabitants, demolished their houses and looted their property.

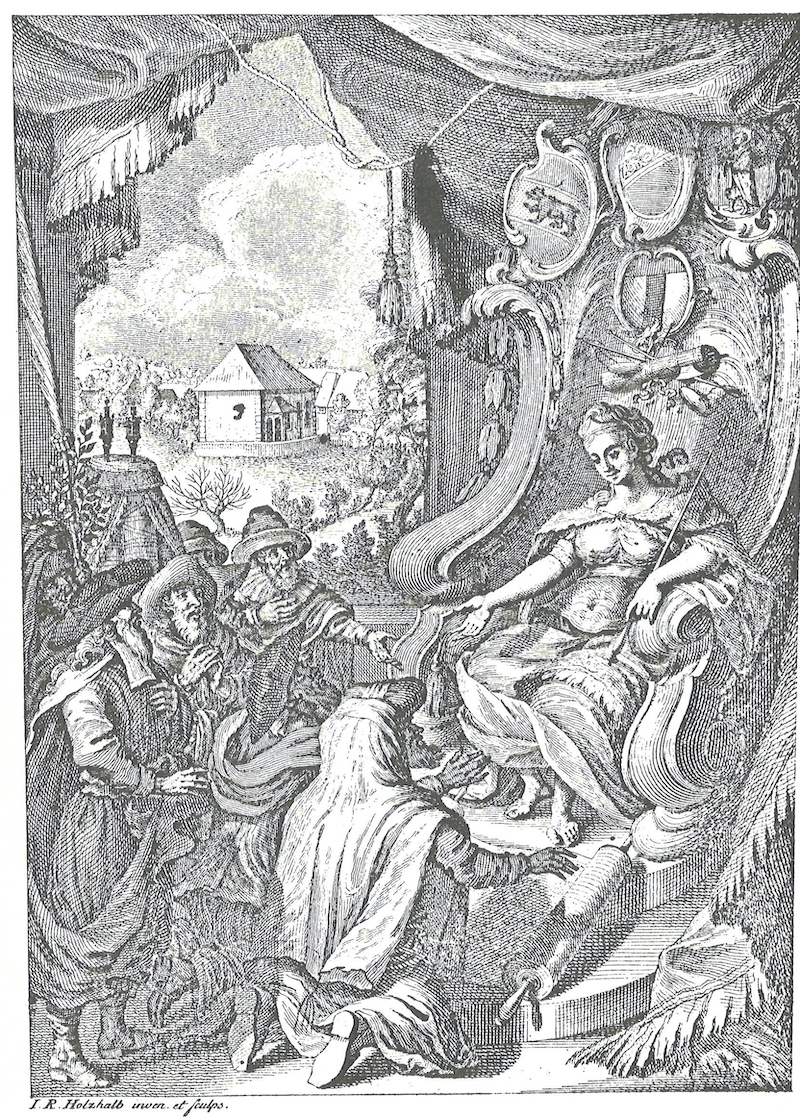

Known later as the Plum War (Zwetschgenkrieg), this outbreak of violence was hardly a spontaneous act. People of different backgrounds gathered to attack the villagers: peasants and craftsmen, former mercenaries and sons of noble families, Protestants and Catholics. Some came on horseback, others on foot – but all were armed to the teeth with guns, sabres and pitchforks.

The law enforcement officers reached the two villages too late and were not strong enough to control the mob. The attackers only stopped and left the scene when they were worn out. How could this act of aggression have happened?

Life under discriminatory rules

Between the start of the 16th century and the end of the 18th century, Jews were barely tolerated and sometimes even faced expulsion in what is now Switzerland. They did not have the right to settle freely in the country and had to purchase so-called protection and safety letters that guaranteed their protection but also entailed paying certain duties and taxes.

Jewish physicians, book printers or money lenders were welcome to live in cities, but there weren’t many of them. In the countryside, on the other hand, larger Jewish communities developed as cattle and horse traders as well as peddlers settled there.

In Switzerland, anti-Semitic prejudices repeatedly rise to the surface. An example is the discussions 25 years ago about the dormant assets of Jewish Holocaust victims, Nazi gold in Swiss banks and Swiss refugee policy during the Second World War, which was characterised by a fear of “Judaisation”.

While the government of the day reluctantly agreed to pay compensation for the lost assets, almost half of the Swiss population wanted to reject all claims, according to a poll by the public broadcaster, SRF. Anti-Semitic stereotypes were regularly used as arguments in letters to newspapers. The Federal Commission on Racism noted a total lack of inhibition when it came to making anti-Semitic statements.

Where did these ideas come from? In a four-part series, SWI swissinfo.ch explores the role anti-Semitism played in Switzerland before, during and after the Second World War.

The other articles in the series:

– The Jews in Switzerland

– Attacks on Jewish department stores 1900-1930

– Left-wing anti-Semitism

Life as a Jew was marked by a long list of discriminatory regulations. Barred from various professions and property ownership and forced to pay special customs duties, the Jews also faced restrictions on the growth of their communities. In some places, they had to pay to use bridges – a rule applicable only to Jews.

Protection and safety letters had to be renewed every 16 years. If a Jewish family had their renewal request turned down, they were forced to move. Sometimes families were even expelled despite their “protected status”. The policy towards Jews was characterised by arbitrary decisions, economic fluctuations and religious-political disputes.

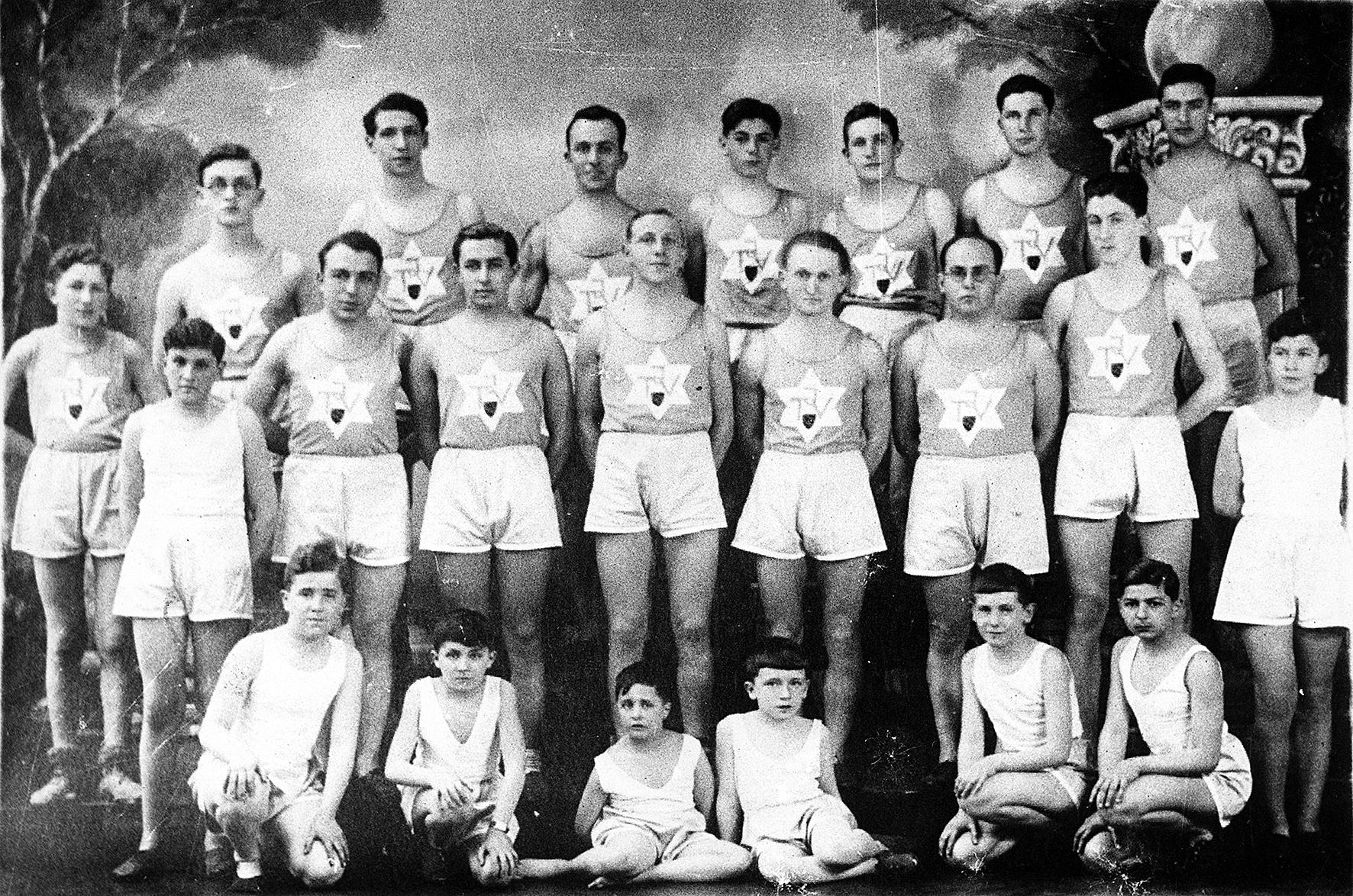

By the 18th century, Lengnau and Endingen in the Surb Valley in the county of Baden, in what is now canton Aargau, were the only places where Jews were allowed to settle and granted certain rights. In 1750, the Confederation gave them permission to establish a cemetery halfway between the two villages. That same year, the Jewish community of Lengnau built their first synagogue, which the people of Endingen could use until they built their own in 1764.

Between 1761 and 1774, the Jewish community in the Surb Valley grew rapidly, doubling in size from 94 households to 180. Its proximity to the Rhine Valley and the city of Zurzach – an important trade hub – made the area economically attractive.

In that same period, however, the Christian communities of the Surb Valley wanted to expel the Jewish people. Only they did not have the power to do it. The county of Baden fell under the jurisdiction of the Confederation, which jointly administered the county.

The issue of expelling Jewish people was raised again and again in the Tagsatzung, a legislative assembly that brought together representatives of the various counties. However, the bailiffs appointed by the regions rejected any expulsion plans – they were, after all, responsible for issuing the mandatory protection and safety letters, a lucrative business.

More

The Jewish cemetery in no man’s land

The end of the old order

The establishment of the Helvetic Republic in Aarau on April 12, 1798 marked the end of the ruling system of the old Confederation. Modelled on the French Republic, it did away with the old system, which was based on divine rights, and replaced it with the revolutionary order of a centralised democracy.

Counties like Baden that had no legal powers and were subjects of the Confederation became democratic cantons with equal rights. Serfdom, feudalism, torture and corporal punishment were abolished for Christians as well as Jews.

More

The birth of modern democracy in the heart of Europe

Supporters of the Jewish Enlightenment demanded the introduction of human and civil rights as well as equal rights for Jewish people – just like they were implemented in France in September 1791.

At the time, Johann Jakob Suter, a physician from Zofingen, was calling for equal rights for all.

“I cannot and will not touch politics the day our constitution states that foreigners who have lived in Helvetia for 20 years without interruption are citizens of this country,” he said. “Under such terms, I will embrace every person, be they Heathens, Turks, Hottentots or Iroquois, like my own brother and fellow citizen. […] Only the term Jew still frightens you!”

Opponents of equal rights considered Jewish people as foreigners and argued that they were not only part of another religion, but of another society. The adversaries used deeply rooted prejudices in their arguments and claimed that the terms “Jew” and “Judas” – the betrayer of Jesus – were related because the Jews were perjurers, and that a Jewish oath had no significance. With this in mind, they said, there was no point in asking the Jewish communities to swear a civic oath to the Helvetic Republic.

The anti-Jewish lobby won. Swiss Jews were considered foreigners, even if they had lived in the Surb Valley for generations.

Revolt in Baden

In September 1802, opponents of the Helvetic Republic launched several revolts known as the Stecklikrieg, which resulted in the temporary collapse of the Republic’s government and marked the end of the state’s fragile monopoly on the use of force.

The attacks on Endingen and Lengnau happened in this power vacuum. Anti-Jewish riots and pogroms usually happen when the use of force has no monopoly for a while.

Following this political turmoil, the county of Baden put in place a new government that had an ambivalent attitude towards the Jewish people. It was keen to investigate the “robberies” of September 21, 1802, and established a commission of inquiry that summoned victims, witnesses and perpetrators. The commission’s meeting minutes revealed that the people who attacked the Jewish communities did not intend to topple the Helvetic Republic. They also provided a unique insight into the aggressors’ vague motivations.

Supporters of the old system claimed that the Jews were the ones who instigated the revolts as advocates of the new order. They drew on conspiracy theories that had gained international currency with conservative critics of the French Revolution. These theories painted the Jewish people as secret masterminds of the revolution who wanted to overthrow the Christian order and rule the world.

Peasants who took part in the 1802 attack thought the opposite was the case and claimed that the Jews benefitted from the old regime. The peasants argued they suffered under the Jewish merchants as much as they suffered under the feudalism of the old regime.

Some of the attackers justified the assault by using old stereotypes from the religious anti-Judaism playbook, which portrayed Jews as foes of Christianity and branded them “Synagogues of Satan”. Others said they’d joined a Catholic procession soon after the riots. Still others said they went to the Surb Valley in retaliation for a Christian who had allegedly had his jaw cut off by a Jew.

More

When Swiss voters gave rights to Jews

In the end, money played a big role. During the attacks, the Jews suffered huge economic losses. Protection and safety letters were destroyed and belongings stolen.

The collapse of Helvetia

After the collapse of the Helvetic Republic in May 1803, rights that had previously been granted were largely revoked. Numerous cantons imposed market and peddling orders that were specifically directed against Jews.

It took some time until the Jewish people were recognised as Swiss citizens with equal rights. The first revision of the Federal Constitution in 1866 granted them the right to settle freely anywhere in the country as well as equality before the law. The second revision, in 1874, finally gave them the freedom of worship and belief. At the cantonal level Aargau became on January 1, 1879 the last canton in Switzerland to grant full citizenship rights to the Jews.

Adapted from German by Billi Bierling/gw

More

How Christian Europe created anti-Semitism in the Middle Ages

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.