An overdue homage to Swiss artist Heidi Bucher

Seamstressing pulled Swiss artist Heidi Bucher into the art world. She began by making portable sculptures before unleashing her creative spirit on architecture and literally “skinning”, as she liked to call her technique, spaces weighed down by history. Bucher missed out on international fame in her lifetime but a retrospective in Bern is giving her work a new shot at broader recognition.

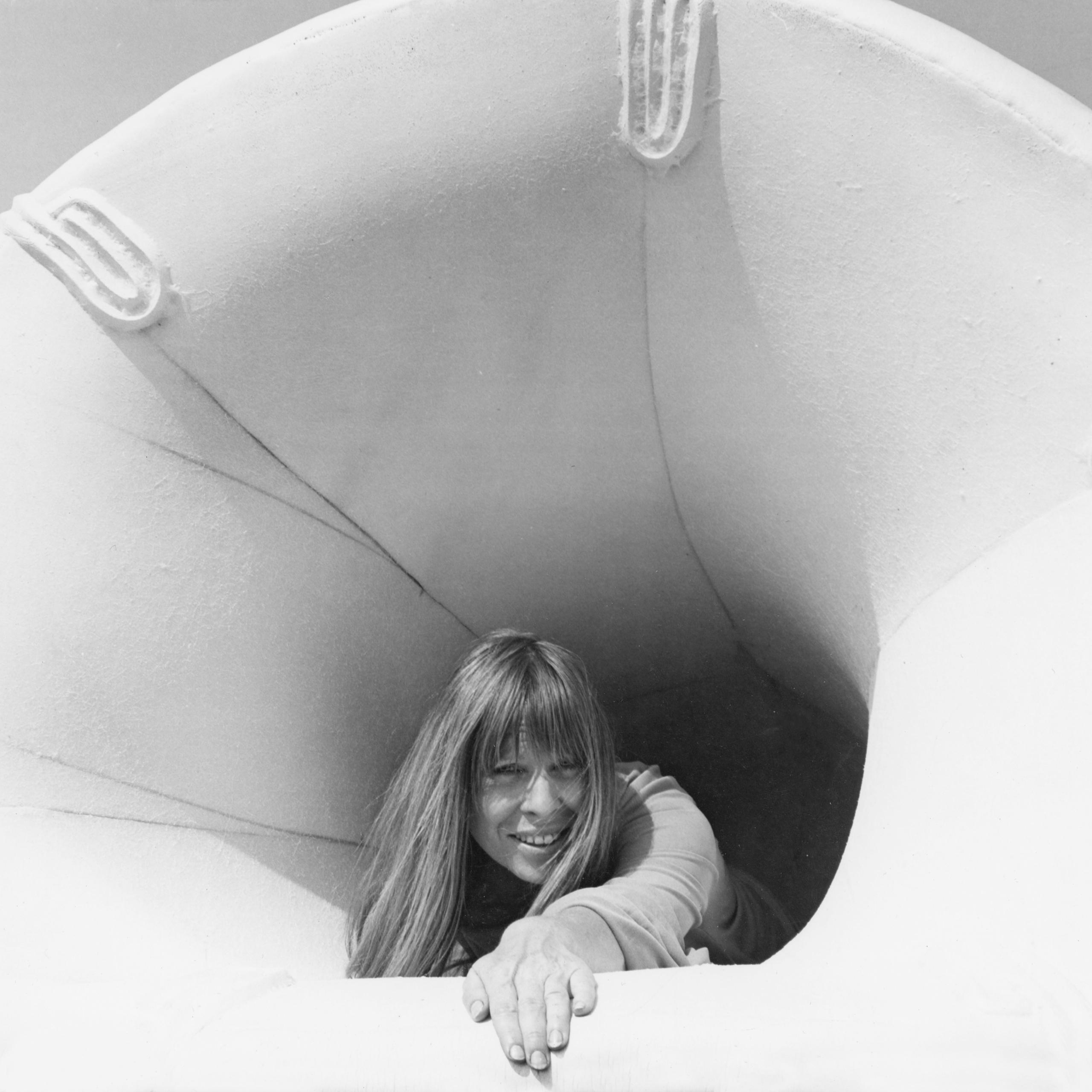

Venice Beach, Los Angeles 1972 – Four large sculptures made of plastic foam slide over the sand, dance about, turn around. Their surfaces glint mysteriously. Have they emerged from the ocean or have they landed from a distant galaxy? In any case, they are alive. Feet poke out here, a hand emerges there, and on occasion, whenever they bow, a head.

The white covering mimics clothing, a vessel, or housing. In the background, the Pacific Ocean disappears into the mist; the waves provide a soundscape for the dreamlike scene. Bodyshells is the name of this series of soft, light and wearable sculptures. Heidi Bucher, her husband and their two sons are testing their range of motion on the California beach.

This was the first major creation by Bucher (1926-1993). The archive film footage of this performance conveys the impression that something essential has been achieved in a utopian manner. Architecture becomes mobile and plastic. Physical spaces protect us but do not dictate our movements. They contain us like the fabric of our clothing without being specifically designed for the male or female body.

Sewing led to architecture

These creations trace their roots back to a less free-spirited reality. Born Adelheid Hildegard Müller, Bucher (her married name) grew up in the northern Swiss town of Winterthur. The daughter of an engineer, she lived in a society where opportunities mirrored conservative gender codes. She completed an apprenticeship as a seamstress in part because this was considered an acceptable occupation for a young woman as it would prepare her for future duties as a housewife.

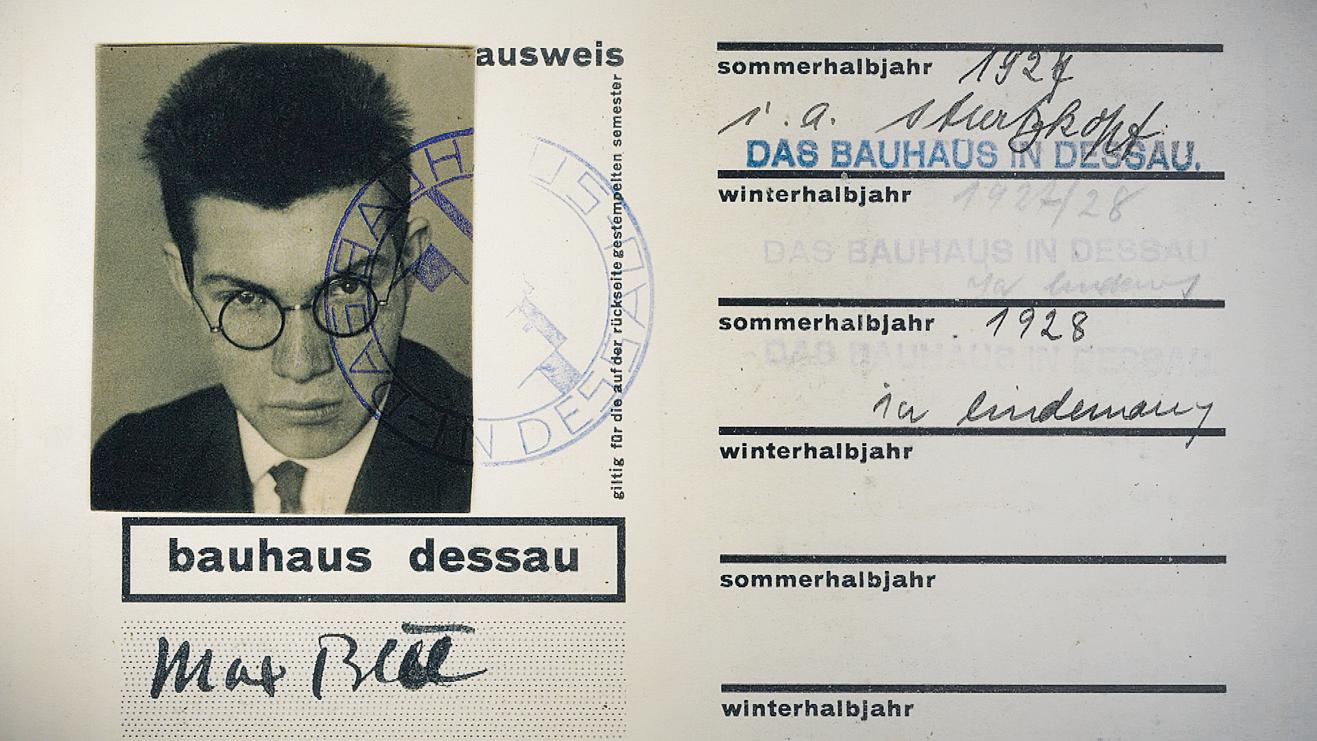

But she also benefited from the chance to pursue fashion and textile studies with Johannes Itten, Max Bill and Elsie Giauque at the College of Art and Design in Zurich. Her creative processes kept a life-long connection to textiles, points out her son Mayo Bucher, who together with his brother Indigo administers the artist’s estate. And this feminine point of departure did not hold her back from expanding her works to absorb architecture, a predominantly masculine domain.

More

Remembering Max Bill, the one-man Bauhaus

California set the stage for Bucher’s emancipation. This is where she had her first exhibition under her own name. Prior to that, she had collaborated with her fellow artist husband, Carl Bucher. Taking advantage of a scholarship provided by the Canadian government to Carl Bucher, the family moved first to Montreal in 1969 and then onto the United States. The couple designed portable sculptures, which they took for walks in the streets of Manhattan. Her work made it onto the cover of the first German edition of fashion magazine Harper’s Bazaar. Yet their exhibition in Montreal in 1971 ran under the name Carl Bucher & Heidi; she was just an assistant, not worthy of further mention.

Los Angeles in the early 1970s was an important location for the neo-avant-garde, performance art, body art and soft sculpture. It was also a hotbed of feminist art and activity. The artists Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro engineered exhibitions for women outside the walls of established institutions. It is fitting, then, that we see Heidi Bucher’s Bodyshells emerge in the open air. Likewise, the later Body Wrappings, a kind of wraparound sculpture made of plastic, were photographed in the open landscape of the Hollywood Hills, the last place where the family lived in California before returning to Switzerland in 1973.

Skinning spaces

The transition from dreamy California beaches to a landlocked country that had just given women the right to vote proved tough. The couple separated in Switzerland. Bucher converted a cold-storage basement that once belonged to a butcher into her artistic studio. From then on, she derived the material for her work from existing spaces.

Her signature technique consisted of applying a layer of latex to the interior of a space and then peeling it off like a skin. She considered these “skinning activities” a kind of metamorphosis, where architecture is freed from its ideology and its history and converted into malleable textiles. She coated the latex with mother-of-pearl, a material that holds the shells of shellfish together like mortar while simultaneously allowing them to shimmer in every colour.

Her first “roomskin” took shape in 1976 within the walls of her studio. She called it “Borg” in a nod to the German word for shelter or safety (Geborgenheit). Later she turned her attention to the cornerstones of her life story: the villa of her deceased parents and the ancestral home of her grandparents. The 1978 work Gentlemen’s study is one of her best known and involved the complete transformation of the room reserved for her father, in which the enthusiastic huntsman kept all his trophies. The patriarchal space was overturned with latex-dipped objects borrowed from the female world: cushions, covers and items such as underwear and stockings.

In the 1980s, her work ventured to historic sites upholding the ideological power structures of the past. In 1987, Bucher “skinned” the entrance of the Grand Hotel Brissago at Lake Maggiore in canton Ticino. This was a house which at first was used to house political refugees during the Second World War before becoming an internment centre for Jewish women and children, thus embodying the ambivalent role of Switzerland during the Nazi era. A year later she made The Consulting Room of Doctor Binswanger at the Bellevue Sanatorium in Kreuzlingen. This work portrays a space in which women were turned into psychiatric patients by doctors diagnosing them with “hysteria”.

A place in art history

Despite the spectacular technique that produced these large-scale works with their high degree of social-political meaning, Bucher’s art remains understudied and underappreciated.

There was little interest in art by women. After the artist’s death in 1993 it took ten years for there to be a major museum exhibition exploring Bucher’s work. When I was a student in Zurich in the early 2000s, one of her pieces stood in the common area of the Art History Institute. It was neither discussed in seminars nor in conversation over coffee.

More

The fight for gender equality in Swiss art institutions

Now, at last, the entire oeuvre of the artist can be appreciated in Switzerland thanks to a dedicated exhibitionExternal link at the Bern museum of fine arts, running until August 7. This major retrospective, Heidi Bucher – Metamorphosis, has travelled from the Haus der Kunst in the German city of Munich to the Swiss capital.

From June, there will also be an exhibition focused on Bucher at the Muzeum SuschExternal link in canton Graubünden in eastern Switzerland. There is a catalogue with her work providing a basis for further study. In a symposium that took place in February in Munich, Bucher’s works commanded the attention of scholars from around the world. Art restorers are working on appropriate conservation techniques for her fragile latex skinnings. The aim is clear: this artist must secure her place in art history.

Even though curators and art experts are finally recognising her artistic genius, it is possible to turn back the clock. The latex has darkened and become brittle. Bucher’s skinnings need to be handled with the utmost care to avoid their destruction. The Bodyshells series had to be reconstructed to appear in the Bern exhibition as the originals had been lost. But they shine silvery white as they once did, as if time had stood still beneath the California sun.

Between sculpture and performance

Plastic granted Bodyshells a new lease of life. Copious archive footage, film stills and photographs, meanwhile, breathe life into the work and character of Bucher. They illustrate how she linked performance and sculpture. We see how she used her bare hands to embalm floors, walls, doors and windows, before drawing on her strength to peel off the latex skin. We see how she wraps herself in skins that glint with mother of pearl.

The artist constructs powerful scenes time and time again. She hung skins out the window, as a housewife would sheets or rugs. She presented a floor skin hanging loosely over the entrance to the ancestral home, as if it was a new coat of arms. For performances, she and her assistants carried the skins through the streets. Only once, at the first (and last) avant-garde Triennale La femme et l’art in 1983 in Le Landeron, Neuchâtel, she wrapped women and one man in latex. As these body wraps hanging now in the museum of fine arts in Bern show, the man shed a few chest hairs in the process.

Joyful metamorphosis

Skinning or flaying may evoke violent mythical motifs, but the dominant element in Bucher’s work is the symbolism of metamorphosis. She repeatedly pays tribute to the dragonfly, which sheds its skin in order to grow and fly. She posed in a costume modelled on the insect, calling it Libellenlust (dragonfly fun). As she peeled off the skin of the Gentlemen’s study using both arms, it seemed as though she was growing wings.

In the film footage and photographs, the playfulness and lightness of Bodyshells comes back into focus, placing the “skinnings” in a less traumatic, rather poetic, even humorous light.

Bucher returned to the sea in the final years of her life. She settled in the Atlantic Ocean island of Lanzarote and subjected local architecture to her ritual “skinnings”. Coloured wooden doors, the transition point between exterior and interior, were central to this period. They were accompanied by watercolours and sculptures crafted from latex and white glue; most of them exploring the theme of water, an element that knows no other state than constant transformation.

Translated from German by Terence MacNamee

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.