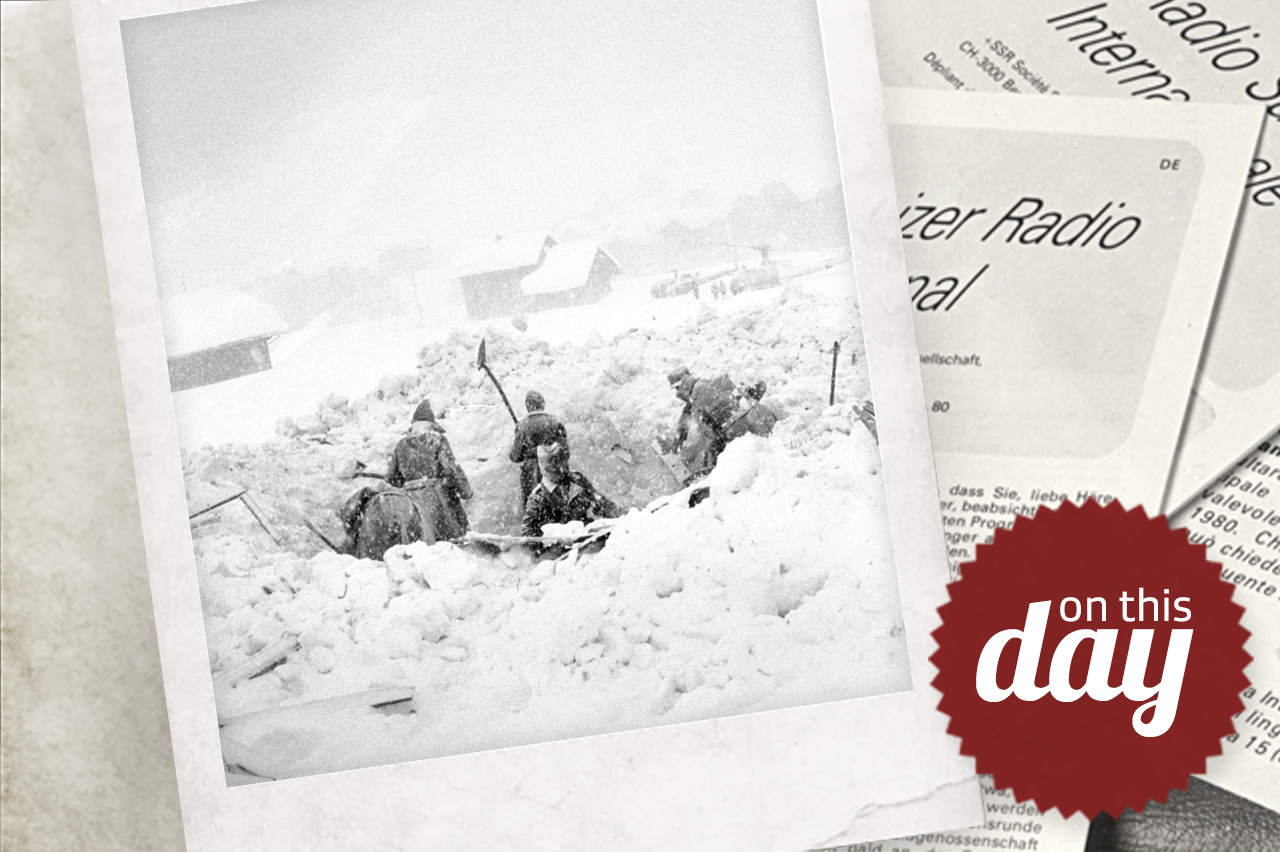

Avalanches: looming danger in the Swiss Alps

Switzerland has a long tradition of avalanche safety and was the first country to publish a bulletin on avalanches twice a day. But how predictable are avalanches really?

Since the 19th century, the Swiss Alps have been attracting tourists from around the world. With the Christmas holidays coming, operators of facilities are getting ready to deal with a winter season that will be different from usual. Due to the pandemic, foreign tourists are scarce, and the ski resorts are having to adopt severe precautions to prevent spread of the coronavirus.

This is an exceptional situation, but it does not take away from the fact that one of the main natural hazards encountered in the Swiss Alps is avalanches.

What causes an avalanche?

Heavy snowfalls, rain, wind, variations in temperature and the slope of the terrain all affect the stability of the snow cover. If something upsets the balance, the mass of snow begins to slide downwards, leading to an avalanche. Even the weight of a single skier can be enough to launch one.

As a result of global warming, more snow is expected beyond the snow line in mountain regions. There will accordingly be an increase in the occurrence of avalanches, warns the Swiss national platform “natural hazards”.

>> The following video shows pictures of avalanches that fell in Switzerland during an exceptional period in January 2018:

When did Swiss avalanche study begin?

According to the Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research (SLF) in Davos, the first centralised group dedicated to the systematic study of avalanches in Switzerland was founded in 1931 at the urging of winter tourism representatives, transportation companies and hydro-electric power stations.

In 1940 the Swiss army started the first early warning system for avalanches, with observation posts in various parts of the country. There was a definite reason for the involvement of the military; a year before, an avalanche above Lenk, in Canton Bern, had swept away an entire company of soldiers. In 1945, at the end of the Second World War, the avalanche control system was transferred into civilian hands, more precisely to the newly-created Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research in Davos.

In 2018, risk management for avalanches by Switzerland and Austria was added to the UNESCO intangible world cultural heritage listExternal link.

Can avalanches be predicted?

“At present we are not able to predict in any great detail where and when an avalanche is going to start off. We can only specify the intervals of time within which avalanches may occur in a given region,” Thomas Stucki, head of the avalanche control team at SLF, told SWI swissinfo.ch.

Since its foundation, the institute has been issuing an avalanche bulletin. In the past, this was disseminated via radio and newspapers once a week, but the bulletin – which marked its 75th anniversary on December 21 – now comes out twice a day throughout the winter. The information is also available on smartphones. It covers the whole of the Swiss Alps, Liechtenstein and the Jura.

“Our avalanche bulletin is similar to the ones in other Alpine countries. But for a long time, Switzerland was the only country to issue one twice a day,” points out Stucki, who is also coordinator of the Europe-wide EAWS early warning system for avalanches.

More

Why the Swiss are experts at predicting avalanches

How does the avalanche control system work?

In Switzerland, 500 kilometres of protective structures – such as metal snow fences – have been built, and extensive belts of woodland protect villages, infrastructure and communications. The Alps are actually more populated than other mountain regions.

“Thanks to prevention strategies, the number of fatalities has remained stable despite there being more people out there.”

Thomas Stucki, SLF

The warning system for avalanches, as well as having 193 automatic measurement posts, relies on a whole network of human observers. About 200 trained people check the presence of fresh snow and collect data throughout Switzerland, and then send this information to the central office.

“There are networks of observers in other countries too, but the density of our network and its level of training and skill are unique,” Gian Darms, an expert at the institute in Davos, told SWI swissinfo.ch in 2018.

Data from the observers are analysed by the institute’s staff, who put together the avalanche bulletin using computer modelling of weather conditions and snow cover. To identify the degree of danger in a region, they use a European scale divided into five levels. This tool is probably “the most significant result of European collaboration,” says Stucki.

How many die in Swiss avalanches?

Since 1936, about 2,000 people have died in avalanches in Switzerland. There have been an average of 100 reported avalanches a year where people were involved. On average, 24 people die in avalanches every year,

In the last 20 years, more than 90% of the fatalities occurred off-piste. The number of fatalities was particularly high in cantons Valais and Graubünden.

The chart shows that notwithstanding prevention strategies, the number of fatalities caused by avalanches has not gone down. Why is this so?

“These days there are more people up in the mountains. As well, people ski not just around the new year but throughout the winter,” Stucki points out. “We can say that thanks to prevention strategies, the number of fatalities has remained stable despite there being more people out there.”

How to be safe in the Alps?

In most avalanche accidents, says the institute, the avalanche is caused by the victims or at least members of their group. According to Stucki, it is therefore crucial to get training to be able to judge the avalanche risk for yourself. Apart from careful preparation and adequate equipment, he stresses the importance of not going out alone.

Translated from Italian by Terence Macnamee

More

What’s the real risk from avalanches?

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!