Einstein’s speed limit still stands

Researchers at the European Centre for Nuclear Research (Cern) who announced last year that sub-atomic particles called neutrinos could travel faster than the speed of light have admitted errors in their work and that Albert Einstein was right.

The scientists said on Friday that the experiment which challenged Einstein’s theory on the speed of light, which postulates that nothing can move faster in the universe, had been flawed and that neutrinos – like everything else – are indeed bound by this law of physics.

The researchers caused a storm last September when they published experimental results showing that the sub-atomic particles could out-pace light by some six kilometres per second.

The findings threatened to up end modern physics and smash a hole in Albert Einstein’s 1905 theory of special relativity, which described the velocity of light as the maximum speed in the cosmos.

But Cern now says that the earlier results were wrong and faulty equipment was to blame.

“Although this result isn’t as exciting as some would have liked, it is what we all expected deep down,” said the Geneva centre’s research director Sergio Bertolucci in a statement. “The story captured the public imagination, and has given people the opportunity to see the scientific method in action.

“An unexpected result was put up for scrutiny, thoroughly investigated and resolved in part thanks to collaboration between normally competing experiments. That’s how science moves forward.”

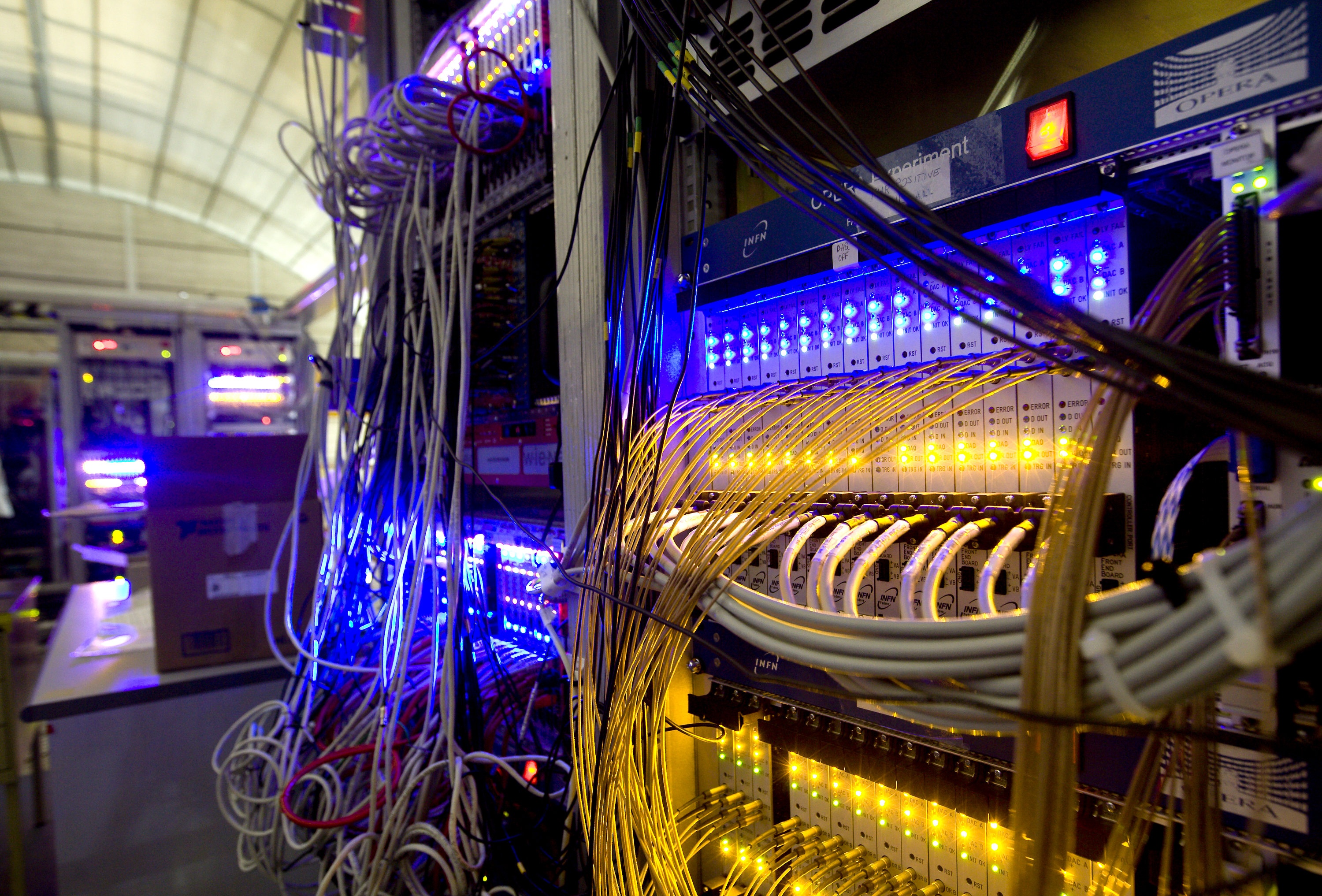

As part of the OPERA experiment, the neutrinos were timed on the journey from Geneva to the underground Gran Sasso Laboratory in Italy, after travelling 732 kilometres (454 miles) through the Earth’s crust.

Consistent

To do the trip, the neutrinos should have taken 0.0024 seconds. Instead, the particles were recorded as hitting the detectors in Italy 0.00000006 seconds sooner than expected, the preliminary experiment had shown. This result remained constant after thousands of tests.

Researchers updated the science community on Friday at the International Conference on Neutrino Physics and Astrophysics, being held in Japan’s ancient capital of Kyoto. Earlier checks had already hinted at the outcome in March.

“The previous data taken up to 2011 with the neutrino beam from Cern to Gran Sasso were revised taking into account understood instrumental effects,” the team said. “A coherent picture has emerged with both previous and new data pointing to a neutrino velocity consistent with the speed of light.”

According to the Cern statement, the mistake can be attributed to a faulty fibre optic timing system. The researchers confirmed in Kyoto a bad connection between a GPS measurement system and a computer accounted for most of the error, adding that the clock system used to time the neutrinos was also insufficiently precise.

The initial findings had been greeted with a combination of excitement and scepticism last year, even from those involved in the experiment, who urged other physicists to carry out their own checks to corroborate or refute what had been seen.

OPERA has been conducted by a team of researchers from Belgium, Croatia, France, Germany, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Russia, Switzerland and Turkey.

The collaboration currently includes about 160 researchers from 30 institutions including Cern, and 11 countries.

Major financial support for the experiment has been provided by Italy and Japan, with other substantial contributions from Belgium, France, Germany and Switzerland.

Cern was founded in 1954 by 12 states, including Switzerland, and now has 20 member states.

Around 6,500 scientists – roughly half the planet’s particle physicists – from around 500 institutes and universities have access to Cern.

Cern built the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the world’s most powerful particle accelerator, which was launched in September 2008. In the LHC, which cost $10 billion, high-energy protons in two counter-rotating beams are smashed together to search for exotic particles.

The World Wide Web began as a Cern project called Enquire, initiated by British expert Sir Tim Berners-Lee in 1989.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.