Ailing oceans ‘pose greatest threat to planet’

Rising sea levels are among the most obvious effects of global warming. But what is happening beneath the surface? Oceanographer David Karl, one of four winners this year of the prestigious Balzan Prize, guides swissinfo.ch through a largely unknown ecosystem.

Prochlorococcus. To most people this means absolutely nothing. And until 1988, David Karl hadn’t heard of it either. Yet it is the most abundant plant organism on the planet.

“How could we not know about it? How can we understand how the oceans work if, until recently, we weren’t aware of its existence?” asks Karl, a specialist of marine microorganisms at the University of Hawaii who will be presented with his award in Bern on Friday.

The fact that these cyanobacteria – aquatic bacteria that obtain their energy through photosynthesis – measure just a thousandth of a millimetre certainly didn’t make the scientists’ job any easier. But it’s not just a question of microscopes.

The oceans, the Earth’s most important ecosystem, remain an unknown that exceeds our capacity for observation, Karl says. “The average depth of the ocean is 3,800 metres – but we know about the top ten metres at most. It’s as if humans are limiting themselves to walking on the surface.”

Born in New York in 1950, Karl had always wanted to go deeper. At the end of the 1970s, he used a submarine to reach the floor of the Pacific. He was the first biologist to observe hydrothermal ventsExternal link and the organisms that live near these fumaroles – “one of the most important oceanographic discoveries in the past 100 years”, he says.

Great Pacific Garbage Patch

From his observations in the middle of the Pacific, and after dozens of expeditions, Karl came to a conclusion about the health of the oceans: overfishing, industrial and agricultural pollution, waste water, oil, plastic… the pressure of a growing global population was altering the equilibrium.

“People had always thought that the oceans were infinitely large and could absorb all our waste. That’s not the case,” he says.

Karl adds that the water in the majority of coastal regions near large cities is polluted. In some places swimming is no longer possible and a splash of water can even be harmful. Out at sea the situation is better, although the traces of human activity are certainly tangible.

He points to the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, an enormous mass of floating rubbish composed mainly of plastic which is double the size of the United States, according to some estimatesExternal link.

“The problem is that the plastic polymers are degraded by the microorganisms. This results in tiny fragments which are even more insidious in that they accumulate in the food chain,” he explains.

The consequences of this depolymerisation of the plastic on marine organisms and ecosystems remains unknown. What is known, however, is that phytoplanktonExternal link are essential for the Earth’s stability and habitability – and have been for four billion years.

“They contribute to the global circulation of nutrients, such as phosphorus and nitrogen, and are responsible for the production of half of the oxygen that we breathe,” Karl said. “They are the marine microorganisms that keep us alive.”

Hidden threat

For him, one of the most worrying phenomena is “without doubt” climate change. “On Hawaii people are well aware of the consequences of rising sea levels, which could hit one metre by the end of the century.”

He acknowledges that Hawaii doesn’t face being removed from the map, unlike other small Pacific islands, nevertheless the submersion of its beaches would jeopardise tourism, a significant economic sector.

Through the monitoring programme HOT (Hawaii Ocean Time-series), which was launched in 1988, Karl provided the first proof that an increase of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere triggers greater acidity in the oceans.

“We know that acidification has an impact on coral reefs and all organisms made of calcium carbonate, for example conches and molluscs. What we don’t know, however, are the repercussions for fish and algae.”

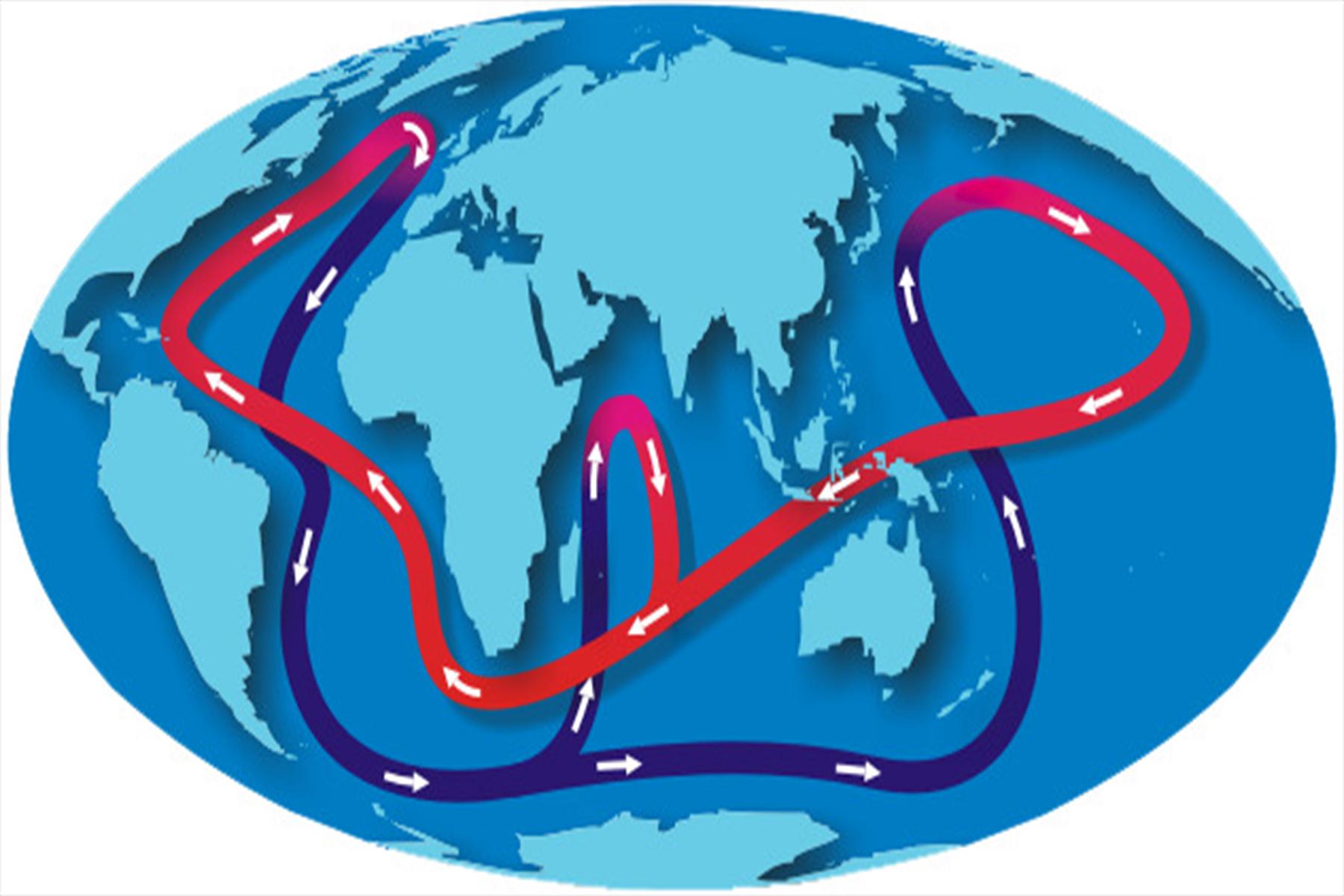

But he says there is another, little-known, factor which poses the greatest threat. Oceans are in a constant churn. The water on the surface, which is denser, sinks to the bottom; the water in the depths then rises, bringing with it essential nutrients for phytoplankton.

“The increasing ocean temperatures and the addition of less dense fresh water from melting icecaps reduces this vertical churn. Layers are forming in the oceans.”

The result, he predicts, is a reduction in photosynthesis – therefore in the production of oxygen – and a change in ocean currents.

From the moon to the oceans

The oceans and the global climate are closely connected, Karl stresses. But he says that for a long time the oceans were ignored during United Nations climate discussions.

“Only in the most recent reportExternal link of the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, published last year, were two chapters included which were dedicated exclusively to oceans.” Karl was responsible for one of the chapters.

It was for this contribution that the Balzan Foundation awarded him one of its prizes this year “for his fundamental contributions to the understanding of the role and immense importance of microorganisms in the ocean, […] work that has yielded significant insights into global change”.

In his speech at the awards ceremony, Karl will quote a book written in the 1950s. “The role of the oceans has been known for years. But to know the Earth better, we have preferred to look to the skies and discover the moon. Maybe, following Kennedy, we need a president who says: ‘We choose to go to the oceans!’”

The Balzan Prize

Eugenio Balzan (1874-1953) was an Italian journalist and businessman who moved to Switzerland (Zurich and Lugano) in 1933. The foundation was created by his daughter in Lugano in 1956.

The International Balzan Prize Foundation says its aim is to “promote culture, the sciences and the most meritorious initiatives in the cause of humanity, peace and fraternity among peoples throughout the world”.

Currently, four annual awards are made: two in literature, moral sciences and the arts; and two in the physical, mathematical and natural sciences and medicine. Prize winners must now use half of their awards for research projects “carried out preferably by young humanists and scientists”.

The Balzan Foundation acts jointly through two foundations. At the “prize” foundation in Milan, the General Prize Committtee, which comprises European scholars and scientists, chooses the subject areas of the awards and makes the nominations. The “fund” foundation in Zurich administers Eugenio Balzan’s estate.

In 2015, the other three prizes went to: Hans Belting (History of European Art (1300-1700)), Francis Halzen (Astroparticle Physics including neutrino and gamma-ray observation) and Joel Mokyr (economic history).

(Translated from Italian by Thomas Stephens)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.