Basel tries to break down integration barriers

Switzerland depends on highly qualified foreigners to remain competitive, but their tendency to live apart from the local population is a matter of concern.

Basel, with its multinational pharmaceutical companies, is attracting more and more skilled workers from abroad. Indeed, expats – people who come to work on a short-term (two to four years) basis – now account for eight per cent of Basel’s population and make an important contribution to the local economy.

The figure looks set to increase: the Federal Statistics Office predicts that in the next 25 years the largest increase in well qualified immigrants will be in Basel.

“Since most of them are qualified professionals, it can be presumed that expats are responsible for about ten per cent of consumption, and pay ten per cent of the taxes,” Guy Morin, president of the Basel City cantonal government told swissinfo.ch.

“We need these qualified people, so we must offer them good conditions and make it easier for them to integrate,” he said.

The canton has been aware of the challenge for some time. A workshop held back in 2009 already expressed concern about the segregation between the expat community and the wider population, describing it as a “situation that is unsatisfactory for both sides”.

This led the canton, the two pharmaceutical giants Roche and Novartis, and the Christoph Merian Foundation, to back a study by Ecos consultancy now published under the title Opportunities and Challenges in the Integration of Expats in the Basel Region, to suggest strategies to improve integration.

“Basel is a model for Switzerland and intends to go on playing a pioneering role in the integration of expats,” Morin declared.

Vital interests

“We are driven by innovation and diversity, capitalising on variety,” Bruno Weissen, head of personnel at Roche, told swissinfo.ch. “We need the best staff we can find, in order to stay at the cutting edge of innovation.”

He summed up in striking terms just how internationally oriented the company is.

“Of the 365 days in the year we work three days for Switzerland, and the rest of the time for other countries.”

Novartis had similar reasons for supporting the study, as head of personnel Hans Locher stressed.

“For a knowledge-based concern like Novartis very able workers are of decisive importance. We have to have expats.”

Since the companies invest a lot of money in the moving costs of expats and getting them acclimatised to their work, they have an interest in seeing that they also settle down well in their everyday life, and do not leave again prematurely.

Understanding the Swiss

Psychologist Marcella Ramelli – herself an expat and a member of the advisory group assisting the study – explained to swissinfo.ch what it means to start a new life in Switzerland unable to speak the local language.

She arrived in Switzerland from Colombia ten years ago with her two children, for what was originally supposed to be only one year.

The first few months were the decisive time. They had all quickly learned German, and the children going to school had helped their integration, since it brought them into contact with other families.

But it is no easy matter to get to understand the social rules in a new country, says Ramelli, whose grandparents emigrated to Colombia from the Swiss canton of Ticino.

“My Czech neighbours in Basel would strike up a conversation whenever they saw me, which I thought really friendly of them. But the Swiss neighbours never said a word. It was only much later, thanks to Swiss friends, that I discovered that this was out of respect and not wanting to be pushy.”

Willingness to integrate

Morin pointed out that the study looks at integration policy from a new angle, quite different from the usual focus on poorly educated and often on criminal foreigners.

It found that expats are often eager to contribute to local society, but frequently run into indifference or hostility. The report wants voluntary organisations to be more aware of their potential, and also calls on the media to write about positive examples of expat integration, to help change perceptions and break down barriers.

It calls for welcoming meetings for new expats to be revived, and to be held at times when the whole family can attend.

“The initial phase is crucial for successful integration, yet obtaining information is often difficult,” it points out.

It stresses the importance of involving everyone in the family: one unhappy member can cause the expat to go home early.

One problem highlighted by the report is schooling. It suggests two ways to create incentives for foreign parents to send their children to local state schools. One is to provide internationally recognised school-leaving certificates, to ease the transition to higher education elsewhere. The other is to introduce immersive learning, to enable children to pick up the language quickly.

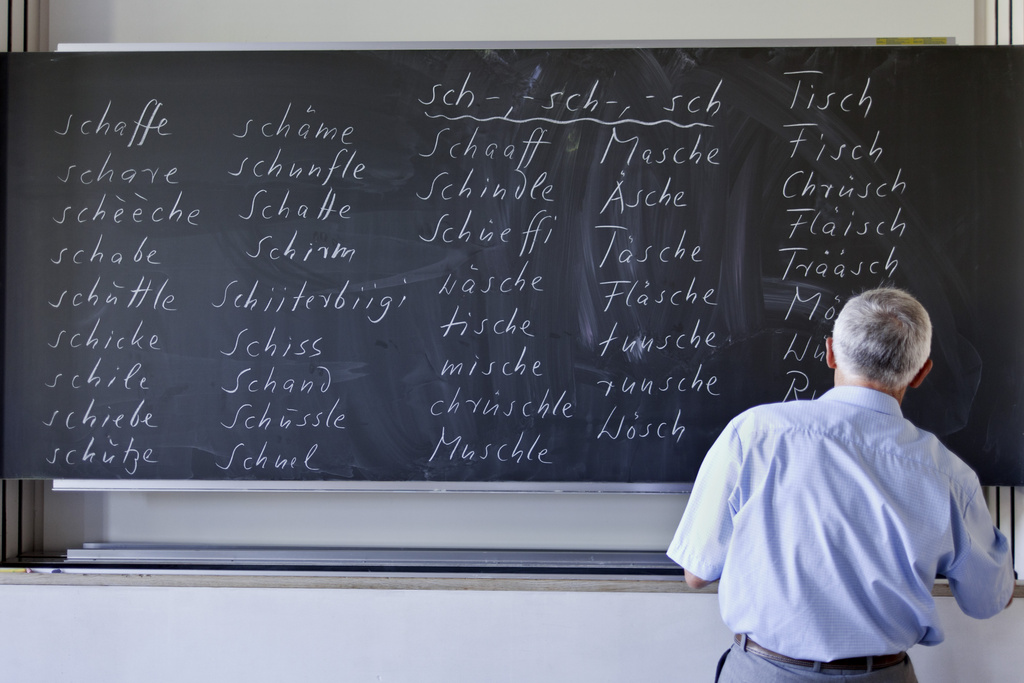

“Language is the key factor in social integration,” it says. For the same reason it advises companies to make intensive language courses mandatory before the expat starts work – and to include the understanding of the local dialect, which “can be a source of frustration”.

Despite the problems facing them, the study found that well over half of expats end up staying longer than they originally planned, becoming what it calls “Baslers with a foreign passport”.

About 36,000 expats live in the cantons of Basel City and Basel Country, accounting for about one resident in 12.

Expats are defined in the study as highly qualified, financially secure professionals, who come to work in Switzerland, initially for two to four years.

About three quarters of them stay longer than two years, and nearly 60% more than four.

In December 2010 there were 118,091 foreigners out of a total population of 467,129 in the two cantons.

Opportunities and Challenges in the Integration of Expats in the Basel Region is the first study to look at the issues facing the growing expat population in any region of Switzerland.

It was written by the Ecos consultancy, which advises businesses, public institution and offices in sustainable development projects.

The research took one year to conduct and cost about SFr 90,000 ($100,000).

The study was supported by the canton of Basel City, the Christoph Merian Foundation and the Basel-based pharmaceutical giants Novartis and Roche.

(Adapted from German by Julia Slater)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.