Beirut – visible and invisible dangers

The Muslim world has celebrated its New Year and the western Christian New Year is approaching. Journalist Werner Scheurer, who lives in Beirut, looks back at the year.

The past year has been relatively peaceful – and here that is not something that can be taken for granted. It’s true that on the surface nothing in Beirut indicates that war might be about to break out – quite the contrary: the city seems positively optimistic.

Everywhere new restaurants and shops are opening, and the old ones are being given a new look. There is construction work going on everywhere: new apartment blocks are springing up haphazardly in every neighbourhood of the city, towering several storeys above all the buildings around.

The city centre, which was largely destroyed in the 1975-1990 war, and is now known as “downtown“, is where the building boom is particularly striking, and appears to be very well planned. New luxury hotels have opened for business this year, and after a “soft opening” of the lavish commercial district, the upmarket shops have opened their doors just in time for Christmas.

The shopping district is called Aswaq Beirut, “Beirut Markets“, and has been built on the site of a once bustling eastern market – but by now only old Beirutis still remember it. All around more future landmarks of the city are springing up, including projects by world famous architects, full of luxury apartments, shops and offices.

No, no-one would think from all this activity that conflict is brewing, and certainly not the growing number of tourists. Lebanon is becoming a more and more popular travel destination worldwide, whether for its historic sites, its natural beauty or the famous Beirut night life.

International tribunal

But despite all the optimistic activity, no-one totally believes in it. Alongside the construction sites stand the ruins of buildings destroyed in the war or which have simply become derelict, evidence of an earlier boom in a past long gone. However, they are a sight that people have got used to over the years.

More disturbing have been some incidents revealing the country’s latent potential for violence: a shoot-out between the bodyguards of two bank directors in a Beirut night club in March, fighting between police and drug dealers in the Bekaa valley.

Even more unsettling have been the occasional explosions of arms depots in southern Lebanon and then the fatal border incident at the beginning of August, when Israeli soldiers came too close to the ceasefire line when they were felling trees. Another cause for concern has been the political and religious background behind two bloody skirmishes in Beirut neighbourhoods.

But today the main basis for the widespread uncertainty – or for some almost the certainty of an impending outbreak of violence – is the months-long controversy about the international tribunal, which has split the country and in the past few weeks has paralysed government business. This Special Tribunal was established by the United Nations Security Council to investigate the bomb attack of February 2005 which killed Prime Minister Rafiq al-Hariri and 21 others.

Stocking up

The first four suspects had to be released without charge after spending years in detention. Now for weeks the whole country has been waiting anxiously for an indictment, which everyone already knows will name members of Hezbollah, the “Party of God”.

The party rejects any such accusation and has launched a broad-based campaign casting doubt on the independence of the tribunal. It is using threats to demand that its political opponents – with whom it sits in a coalition government – should distance themselves from the tribunal.

In May 2008 Hezbollah militiamen demonstrated yet again their ability to paralyse the capital, and thus the whole country, overnight. They occupied entire districts of the city, besieged government institutions, reduced the media of their political opponents to silence and blocked the airport. It is quite possible that they could do the same again one night.

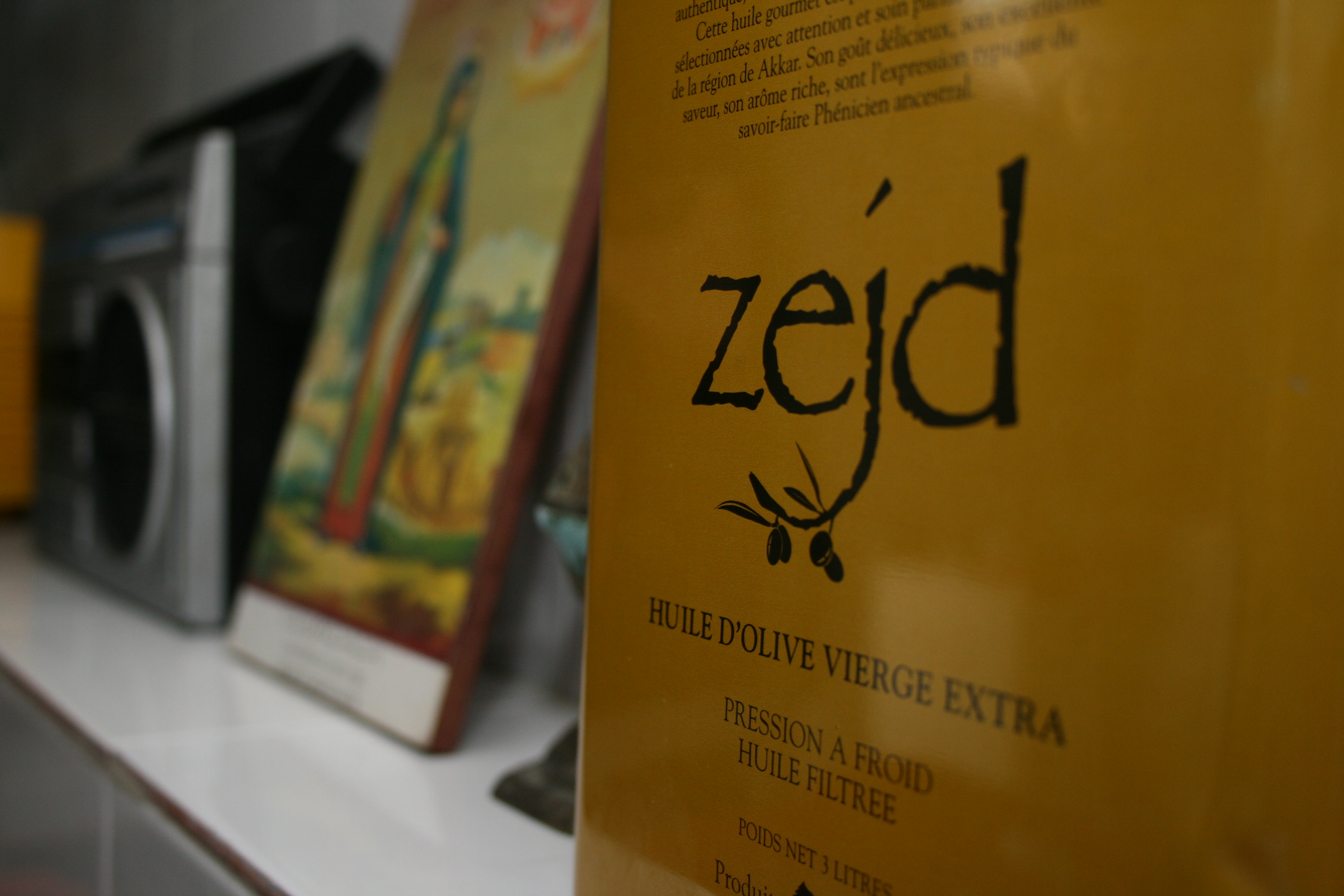

In the face of such a possibility the Swiss resident recalls the snappy Cold War advice from his homeland: “Kluger Rat, Notvorrat!“, meaning: “Stock up on essentials”. Every family was supposed to keep a stock of basic foodstuffs at home, so as to be prepared for shortages that might occur if there were a crisis of any kind.

And in Beirut it is indeed possible that you couldn’t get to the shop just round the corner for several days, or that it wouldn’t have everything in store. So stock up. It doesn’t take long to find on the internet the good advice offered by the Swiss government as to what such emergency supplies should include: they range from basic foodstuffs, to batteries for the radio to loo paper.

Swiss advice

It’s a relief to see right away that the information doesn’t come from the defence ministry but from the Federal National Economic Supply Office, part of the economics ministry. In 2010 the reason for people in Switzerland to hold emergency stocks is no longer because of wars and conflicts, but rather pandemics and natural disasters.

And you suddenly realise that Lebanon is exposed to other dangers, not only the political ones. The country lies at the northern end of the Jordan Rift Valley, the prolongation of Africa’s Great Rift Valley fault. That is why the region has a long history of earthquakes – a particularly strong one devastated Beirut in 1759, causing thousands of casualties. In the Bekaa valley the mighty pillars of the famous Roman temple of Baalbek collapsed.

So that is another reason to stock up for emergencies. But Switzerland does not provide only good advice. It is also participating in a campaign run by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in Lebanon to raise people’s awareness of the risk of earthquakes and other natural disasters, and is supporting the training of emergency medical personnel and construction specialists.

After all, emergency provisions only last a few days.

Many Swiss authors have been drawn to live elsewhere in the wide world. Their writings give us a better understanding of unfamiliar places.

swissinfo.ch has invited a number of authors, some well known and some not so well known, to share their observations of their adopted countries.

The opinions expressed by guest author contributors are theirs alone, and do not necessarily reflect the editorial line of swissinfo.ch.

Scheurer, 55, has lived in Beirut since the middle of 2009.

He is the correspondent of the Swiss weekly WOZ.

In the 1990s he lived in Cairo for five years.

Rafiq al-Hariri, a successful businessman, was prime minister of Lebanon from 1992 to 1998 and 2000 to 2004.

He is credited with reconstructing Beirut after the 15 year civil war which ended in 1990, leaving the city devastated.

He was assassinated in an explosion in 2005, along with 21 other people, a few months after resigning in protest at Syrian influence in Lebanon.

The Syrian secret services were quickly blamed for the killing, and after public protests, Syria withdrew its troops from Lebanon.

An inquiry into the assassination was set up by the UN, which has spent several years on its investigations.

It has been widely reported that Hezbollah will be accused of carrying out the killing.

However, Hezbollah has blamed Israel. In October 2010 it carried out a simulated takeover of Lebanon, and has threatened to put it into practice should the International Tribunal indict its members.

Switzerland has been helping to train volunteer rescue workers in Lebanon.

A group of 19 received their diplomas as instructors with the Lebanese Emergency Medical Services in December 2010.

The programme was run by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, in conjunction with the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), the Geneva University Hospitals, and the Geneva Paramedical College.

The ICRC has several activities in Lebanon.

These include visiting detainees to assess their treatment and conditions, improving medical care for Palestinian refugees and assisting the authorities in rehabilitating water infrastructure in remote areas.

It also supports the Lebanese Red Cross, helping it to improve its readiness for dealing with emergencies and its ability to deliver services.

(Translated from German by Julia Slater)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.