Dirty money remains threat to society, says watchdog

The global fight against money laundering is bogged down by inconsistent enforcement and a failure to keep pace with increasingly sophisticated criminal activity, according to a Swiss anti-corruption watchdog.

Switzerland, too, must work harder to prevent criminals from using its banking system to hide ill-gotten gains, an index published by the Basel Institute on Governance indicates.

The NGO’s “Basel AML (anti-money-laundering) Index” perceives the money-laundering threat to society at around the same level as last year, both worldwide and in Switzerland.

+ Dirty money thrives without banking secrecy

The study notes that while countries have more tools at their disposal to detect criminal funds, they lack sufficient cooperation and political willpower to translate this into concrete progress.

“When it comes to tackling dirty money, most countries are taking one step forward and four steps back – and remaining too many steps behind criminals seeking to launder illicit funds,” the institute said. Fixing weak spots in the financial system “is long overdue”.

Secretive Switzerland

With a slightly improved score of 4.55 from last year (10 is the worst possible mark), Switzerland remains a middle-ranking country for money-laundering risk.

The risk of political corruption or ecological crime are low in Switzerland, but the country is dragged back by ranking second in a Tax Justice Network list of the most secretive financial sectors.

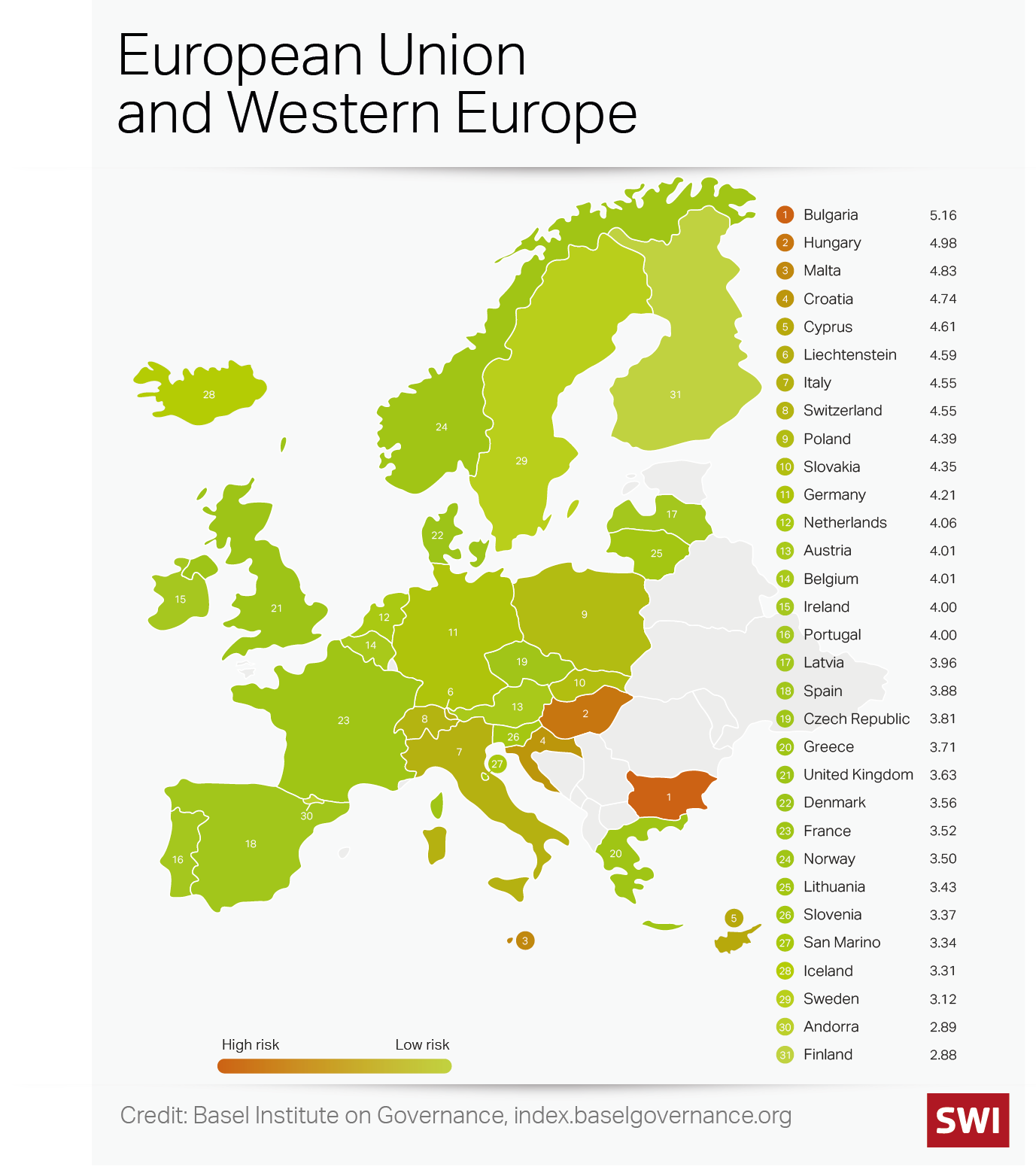

Because the Basel AML Index added more countries this year and changed some methodology, its global ranking is not directly comparable to the last edition of the index. Regionally, Switzerland is considered the eighth most likely venue for dirty money out of 31 countries in the European Union and Western Europe.

Despite ending banking secrecy and signing up to more rigorous international AML standards, Swiss banks are still criticised for allowing too much dirty money to flow through their vaults.

In August, the Swiss Federal Audit Office warned that legislation fails to keep pace with money-laundering developments and that Switzerland “seldom anticipates developments at international level”.

New laws targeting the trade of real estate, gold and precious stones have either been introduced recently or will come into force at the start of next year. But lawmakers have rejected calls to increase pressure on lawyers to reveal suspicious activities by their clients.

Swiss laws that have recently come into effect are not reflected in the Basel AML Index because their effectiveness has not yet been assessed by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), an international body that sets AML standards and monitors compliance by countries. The next FATF assessment of Switzerland will not start before 2024.

Russian isolation

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will have both negative and positive effects on the fight against money laundering, Basel AML Index project leader, Kateryna Boguslavska, told SWI swissinfo.ch.

“The conflict has revealed huge gaps in the global anti-money-laundering framework,” she said. “This has resulted in a better understanding of the importance of cooperation between countries and a greater international political will than ever before to fight this type of crime.”

But Russia’s isolation from much of the international community is currently hindering efforts to track down dirty money.

“To investigate and prosecute money-laundering offences we need international cooperation,” Boguslavska said. “It is obviously more difficult to prosecute illicit Russian money flows without cooperation from Russia.”

Basel AML Index

The Basel AML Index measured the anti-money-laundering efforts of 128 countries, including their legal systems, the transparency of financial and public sectors and susceptibility to corruption and bribery. The index drew on data from the FATF, Tax Justice Network, the World Bank and other sources.

The Basel Institute on Governance was set up in Switzerland in 2003 as a non-profit body to counter corruption and financial crime.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.