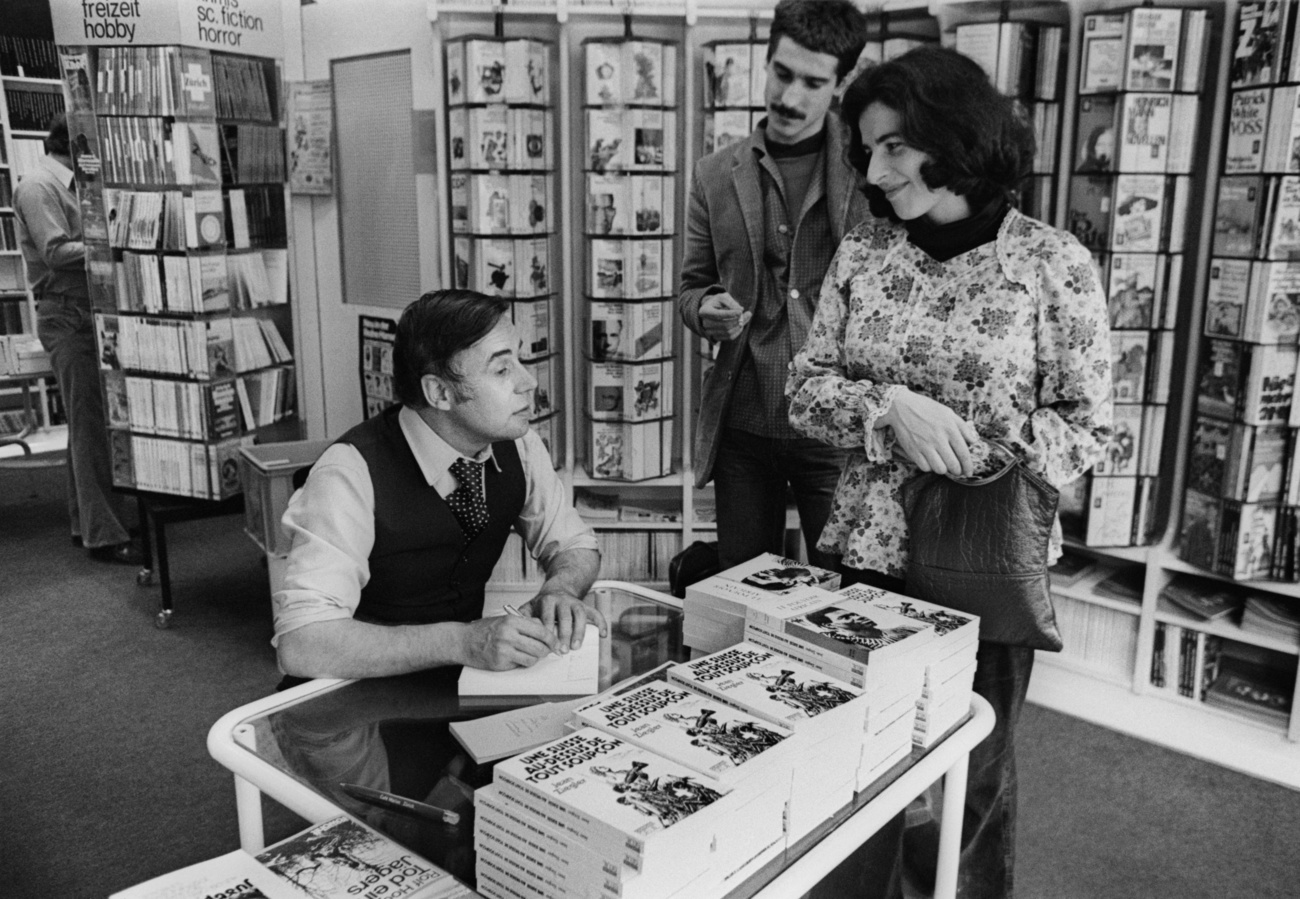

Jean Ziegler – the thorn in the side of Swiss capitalists

Sartre and de Beauvoir politicised him in Paris; Che Guevara gave him career tips. The sociology professor Jean Ziegler is one of the most trenchant critics of capitalism and Swiss business practices. SWI swissinfo.ch interviewed him.

Jean Ziegler, 88, retired professor of sociology, is one of the most famous critics of globalisation in the world. He was professor at the University of Geneva, from 1967 to 1999 (including a four year pause) a member of the Swiss Parliament for the Social Democratic Party (SPS), and a United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food. He is currently a member of the UN Human Rights Council (UNHCR).

Ziegler has written numerous bestsellers, but has also been repeatedly criticised for his connections to dictators such as Libya’s Moammer Gaddafi and Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe. He lives with his wife in Russin, a municipality in canton Geneva.

SWI swissinfo.ch: You’re considered one of Switzerland’s sharpest critics. What made you who you are?

Jean Ziegler: I was born into bourgeois surroundings in Switzerland and had a happy but very narrow-minded childhood. Nonetheless, whenever I encountered poverty, it shocked me. But my father always said, “God intended it to be that way”. That’s what was called predestination. I found it unbearable.

Then, in Paris, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir finally gave me the tools with which to understand the world and to fight for change. Thanks to them, books became a weapon for me.

SWI: What part did Che Guevara play in your life?

J.Z.: Che laid down the strategy in my struggle: subversive integration. The aim was meant to be to infiltrate the institutions and to use their power for my goals. That’s why I became a university professor, parliamentarian and then even a special rapporteur for the United Nations.

SWI: You were a member of the Swiss parliament from 1967 to 1999 and gained recognition for submitting a record 38 legislative proposals in a single year, in 1989. Did entering politics help to change things?

J.Z.: Yes, although the parliament in Switzerland is in fact powerless. You actually get paid very little as a parliamentarian, so when you get elected – above all when you belong to the right party – you get offered a post on the board of directors of companies like Nestlé, Roche, UBS and Credit Suisse, where you earn hundreds of thousands of Swiss francs. That way you become a mercenary.

One example: the OECD was pushing for the money laundering laws here to be tightened, because the Swiss laws didn’t apply to lawyer’s opening offshore bank accounts. The government was pressured into proposing the law. And then in September last year parliament rejected the proposal. The banking oligarchy is always in the majority.

SWI: You’re considered to be one of those responsible for the abolishment of banking secrecy in Switzerland.

J.Z.: Banking secrecy hasn’t disappeared. The robber banks continue to exist. Scandals like the one triggered by the Suisse Secrets leak show that it’s business as usual. However, the automatic exchange of information is making life difficult for speculators, because in the end they’ll be exposed.

SWI: Your books have always caused uproar. The publication of one of your most famous books, Die Schweiz wäscht sich weisser (Swiss Whitewash) from 1990, went off like a bomb in Switzerland. Afterwards you were sued nine times by banks and lawyers, and even dictators. In the end you lost everything, including your seat in parliament.

J.Z.: I was being threatened at the time and was getting anonymous phone calls. What the press wrote is that the hidden financial hand of Moscow was lurking behind my stories. There were lunatics who thought that I was to blame for their divorces. I had to live under police protection for almost two whole years. My family suffered a lot during this period. But I’m not complaining: I’m a privileged person.

I lost all the lawsuits. Each of the [book’s] nine translated versions was treated as a separate crime. But I thought to myself that it was also an opportunity to fight using the courts – the bankers had to answer the questions that were raised there.

SWI: But the consequences were bitter for you.

J.Z.: My university salary was confiscated. I could only exist on a bare minimum. Everything that I’d earned with my books was blocked. The house you see here belongs to my wife. We were able to save a couple things just in time, but nowadays even my car is rented.

SWI: What do you think about direct democracy, a particularity of the Swiss political system?

J.Z.: In my opinion, direct democracy is a good thing, but in such an unequal society as ours – 2% of capitalists in our country control over half of Switzerland’s entire wealth – those with money subjugate the majority. The knee-jerk retort to each people’s initiative on a piece of proposed legislation is [the argument] that the proposal will lead to increased unemployment and higher state spending. Cowed by the propaganda, people vote against their own interests: against the suggested fifth holiday week; against unified health insurance, which would have lowered premiums by 30%; or against raising public pensions.

SWI: In spite of all this, you held a series of conversations with one of the most well-known capitalist figures in Switzerland, the former Nestlé president Peter Brabeck …

J.Z.: My political battles have always been inspired by one of Sartre’s remarks: in order to love people, one has to virulently hate the things that oppress them, not the individuals who oppress them. So if Brabeck doesn’t increase the company’s capital, he’d no longer be president of Nestlé. He’s not the problem – the multinational companies are the problem.

According to figures from the World Bank, in 2021 the five hundred largest transnational corporations jointly controlled 52.8% of global GDP. They’re obsessed with only one strategy: profit maximisation in the shortest time possible and at any price.

SWI: Nevertheless, in China capitalism has lifted 800 million people out of poverty in the last 40 years, particularly following Deng Xiaoping’s reforms in the 1970s. Isn’t that proof of capitalism’s efficiency?

J.Z.: The capitalist mode of production is undoubtedly the most energetic and creative ever known to humanity, but it’s beyond the control of nation states or the unions. Corporations have a power that no king or pope could ever have dreamed of. What this ends up in is a cannibalistic world order. We’re all fighting against hunger. We’re fighting against the unlimited power of the multinational firms. We’re fighting against global warming.

SWI: Is capitalism responsible for climate change?

J.Z.: Obviously. There’s no public authority, in the name of the common good, that can enforce the normativity agreed by the participating states in the context of the Paris Agreement. The destruction of the planet is therefore the direct causal result of capitalism. Take the 2015 Paris Agreement. The aim was to limit global warming to 1.5°C compared to pre-industrial levels. Here we are in 2022, and instead of being reduced oil production has tripled for profit reasons.

SWI: What do you think of the young people protesting on the streets of the world’s capitals under the banner of the Fridays for Future movement?

J.Z.: For me this is the wonder of history. This sudden burst of consciousness is amazing, because it’s their planet. All at once there’s this extraordinary movement – a kind of insurrection of consciousness. And it’s beginning to look very interesting because they’re starting to think about the impact of multinational companies. They see the devastation, the storms, the deserts, the famines. That really is an awakening!

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.