Can commodity traders get a grip on their soy supply chains?

An experiment underway in Brazil shows how companies buying and selling vast quantities of ‘soft’ commodities like soy are trying to trace products back to their origin to reduce deforestation. Can it work?

While most people have heard of the Amazon rainforest, few outside Brazil know of the Cerrado. The tropical savanna occupies a little over 20% of the country’s land and is South America’s second-largest biome after the Amazon, hosting around 4,800 species of plants and vertebrates found nowhere else. The region also accounts for half of all soy grown in Brazil, the world’s second-largest producer of the crop after the US. Commodity firms – like Swiss-based Glencore – source soy from here which they sell on to companies producing food for humans and animals.

But soy production in the Cerrado is leading to its rapid deforestation. According to Chain Reaction ResearchExternal link, soy production increased by 10% between 2000 and 2017 resulting in an estimated 2.83 million hectares of deforestation. The Swiss NGO Public Eye wants commodity firms to take more responsibility for the destruction given their level of involvement on the ground.

“Traders are often closer to the production stage compared to some food companies who do not buy directly from farmers,” says Silvie Lang, Public Eye’s soft commodities specialist. “They have become more and more vertically integrated and can in most cases no longer be considered simple traders or intermediaries.”

An experiment in traceability

The Cerrado’s unique combination of rich biodiversity, lower level of legal protection than the Amazon and high crop production potential makes it especially vulnerable to habitat destruction. Landowners are only required to set aside a minimum of 20% of their land as nature reserves and are free to convert the rest into soy farms.

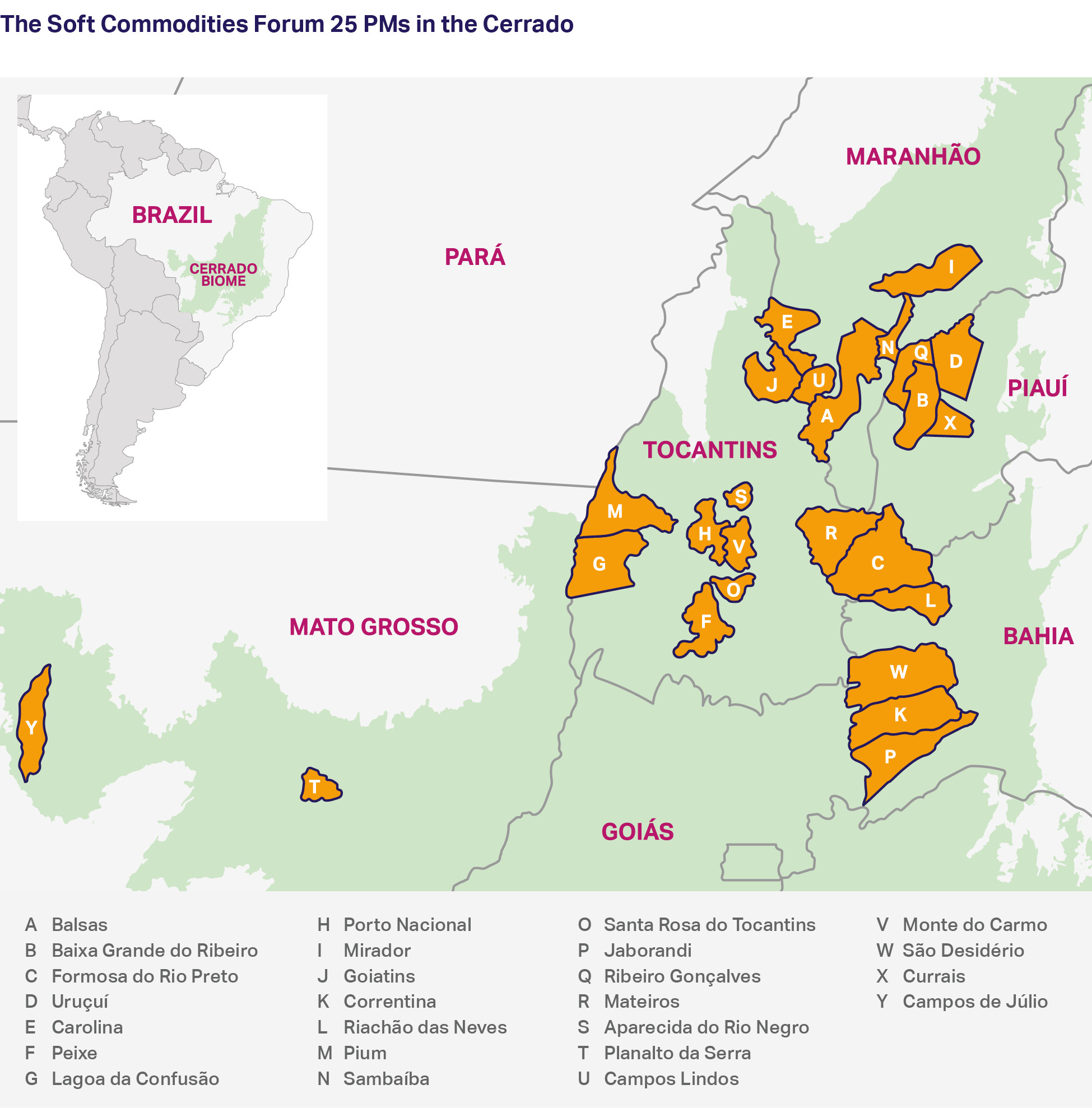

This also makes the Cerrado the ideal place for some of the world’s biggest commodity firms to join forces and focus their efforts to reduce conversion of native vegetation into soy plantations. Known as the Soft Commodities Forum (SCF)External link, the partnership – which comprises Glencore, Bunge, ADM, Cargill, LDC and COFCO – is conducting a traceability experiment in 25 high-risk municipalities in the Cerrado. The goal is to trace all soy sourced from these municipalities back to the farm and achieve 95% traceability rate by the end of 2020. By knowing which farms supply soy, those behind the partnership hope it will become easier to monitor which plots of native vegetation get turned into soy fields.

The six commodity firms involved in the project currently source between 21 and 38% of their Brazilian soy from the Cerrado. Of that, for some companies, as much as 40% comes from the 25 high-risk municipalities that are the current focus of the SCF.

“The hope is that the lessons learned in the current focus areas will be applicable to the whole Cerrado, and other geographies beyond it as the work of SCF expands,” says Diane Holdorf, spokesperson for the SCF.

Based on the latest report from December 2019, the six commodity firms put together can trace an average of 75% of the soy sourced from the 25 municipalities in the Cerrado. The figure would be much higher were it not for Cargill, which only managed 61.8% traceability whereas the other firms all achieved over 90%. Switzerland-based Glencore does well at 99.4% traceability, but a closer look reveals that the majority (57.1%) of its soy is sourced indirectly via intermediaries like aggregators and cooperatives and not directly from the farms themselves. Indirect sources do not count towards the 2020 target of achieving 95% traceability to farm.

Soy’s unique challenges

The reasons for such difficulties in achieving full traceability have become more apparent as the SCF continues to work towards its goal of full traceability to farm. For example, there is a lack of continuity when it comes to suppliers. A farmer may supply soy to one company one year but decide to sell the crop to someone else the following year if they get a better price, making tracing more complex.

“Supplier turnover is a reality for all annual crops, where producers have the opportunity to check prices and make business decisions on what to sow year on year. This might differ from perennial crops like coffee or palm oil where contracts between buyers and producers tend to be longer term,” says Holdorf.

Plots planted with soy also cover smaller areas that are spread over much larger geographic zones than other soft commodities like palm oil. And soy is often rotated with other crops, meaning that a field containing soy one year could have another crop the following year. These factors make satellite monitoring of soy production harder and more expensive than for other crops like coffee.

There are also economic factors beyond the control of commodity traders. For example, a 2019 reportExternal link by The Nature Conservancy (TNC) claims that it is cheaper for soy producers to buy and clear land covered with native vegetation than to buy or lease land that has already been cleared in the Cerrado.

When it comes to expanding soy production, the return on investment is higher for already-cleared land over the long term, according to the TNC report. However, most leases in the Cerrado are of five years duration which makes long-term planning wishful thinking. Currently, there is little incentive for farmers to set aside more than the legal amount required by the Forest Code, which for the Cerrado is set at 20%, an amount, considered by many, insufficient to protect native vegetation and vital ecosystem services.

“Balancing Brazil’s right for economic growth and the environmental imperative to conserve native vegetation is not simple,” admits Holdorf.

This month, the SCF announced it was partnering with the NGO Solidaridad Brazil to help find ways to make sustainable soy cultivation more profitable for farmers. The initial focus will be on the Matopiba area which has a high rate of native vegetation conversion.

Changing political winds

The focus on parts of the Cerrado will also be difficult to scale beyond the municipal level, not least because the administration of Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro has sent a signal by removing certain environmental protections in the Amazon and other parts of the country.

“Various farmers who feel supported in clearing their land by president Bolsonaro, are even calling on traders to support the end of the Amazon Moratorium – a ban on buying soy from areas cleared in the Amazon forest after 2008,” says Lang.

Ironically, it was the Amazon Moratorium, which the commodity traders adhered to on a voluntarily basis, that pushed soy production to the Cerrado. A Cerrado Manifesto developed along the lines of the Amazon Moratorium has not been endorsed by any traders. Cargill has publicly voiced its refusal to back it.

As such, the Cerrado will likely continue to be an important soy production region for Brazil. However, Public Eye argues that commodity firms have the best chance of influencing soy producers’ practices, since the firms are involved at various stages of the supply chain, from storage, crushing, producing edible oil and biodiesel products to infrastructure and exporting.

Although she finds traceability important, Lang says that SCF’s work to trace soy back to the farm is ultimately only half the battle.

“It largely depends on how robust the monitoring and remediation mechanism is, and which actions companies are willing to take based on the conclusions.”

A few weeks after this article was published the SCF released a mid-year report with updated soy traceability figuresExternal link for the six companies.

More

Why little Switzerland matters for the survival of tropical forests

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.