Climber remembers “impossible” ascent

A young Swiss mountaineer accomplished exactly 50 years ago what was then deemed “impossible”, orchestrating the first successful ascent of a daunting Nepali peak.

Max Eiselin of Lucerne was 28 at the time. He had already been part of one attempt on Dhaulagiri, one of 14 peaks in the world above 8,000 metres.

Eiselin told swissinfo.ch that with an idea for a better route and a bit of innovation his leadership helped six members of the expedition make it to the summit on May 13, 1960.

Eschewing corporate sponsorship, Eiselin and his team came up with a unique way of raising funds from ordinary citizens. And his expedition was the first in mountaineering to use an airplane to move people and supplies from Nepal’s low valleys into the mountains.

“It was called impossible, devil difficult,” Eiselin says of Dhaulagiri. “Of course, young climbers are stirred up by this. They want to prove they are good enough to climb something called impossible.”

Back in the 1950s, mountaineers were racing to become the first to stand atop Himalayan peaks, some of the last untouched places on Earth. And the pride of nations went with them.

It was French pride – and government cash – behind the expedition that in 1950 became the first to summit an 8,000-metre mountain.

While the French team gloried in the success of reaching the top of Annapurna, their initial target was Dhaulagiri. The climbers had changed course after examining the peak, calling it “impossible”.

Summit fever

The Swiss, especially Eiselin, also had summit fever.

Sitting among the rugged boots and climbing ropes in the Lucerne branch of his chain of outdoor stores, Eiselin Sport, Eiselin, now 78, remains thin and fit. He says he started mulling over climbing Dhaulagiri in 1953, when attending a lecture that discussed possible routes.

In 1958, he was selected to join a Swiss expedition to the mountain. The Nepali government only allowed one group to go per year, and since the first attempt every one had tried the same route to the summit.

“There,” he says with a smile, “I encountered that all the previous expeditions took the wrong way.”

He lobbied for a permit, and with help from Swiss living on the Indian subcontinent, landed one for 1960.

He had a year to prepare. All he had to do was assemble the team, raise the large sum it would take for such an expedition and avoid the pitfalls of previous efforts.

Logistics master

Eiselin selected five Swiss mountaineers, as well as other European climbers, to make up the group.

The first challenge was raising cash. Instead of corporate sponsorships, the team set up a bank account. Swiss newspapers publicised the team’s plan and account number, as well as its promise to send a postcard from Nepal to anyone who contributed.

“I thought we should at least try,” Eiselin says. “I was sceptical.”

Amounts as small as SFr5 came from all over Switzerland, as well as donations from citizens in other European countries. “Without these postcards the expedition would not have been possible,” Eiselin says.

Next, Eiselin tackled the problem of how to get the supplies the expedition needed to Dhaulagiri.

The trek from the valley to the mountain usually took five days. Then there were the multiple camps the team must set up progressively farther up the slope to allow the climbers to acclimatise. All this usually required a small army to carry provisions.

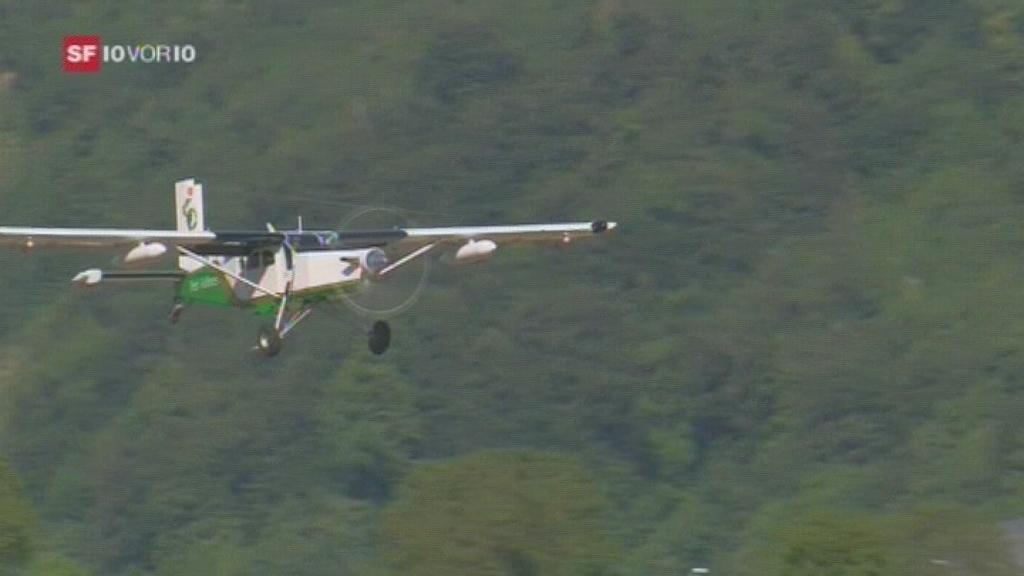

To cut down on time and expense, Eiselin wanted to try using an airplane. He recruited two Swiss pilots, Ernst Saxer and Emil Wick, both of St Gallen, to fly a light aircraft nicknamed “Yeti”. The pilots had logged many hours of mountain flying, including landing on glaciers.

In an interview earlier this year, Eiselin remembered reaction to the plan.

“Understand that to even my good friends, my flash of inspiration to use a glacier plane was absurd,” he says.

On the mountain

Yet the Yeti managed to shuttle men and materials to 5,700 metres, which is still an aeronautical record.

The expedition did experience a few setbacks. A mechanical problem grounded the Yeti, forcing Eiselin to hike back down the valley to fix it. “I lost my acclimatisation in this time,” he says.

Then the Yeti crashed as it was taking off from 5,700 metres. The pilots were safe, but the plane could not be fixed. It remains to this day on the mountain.

The expedition by now, however, had split into smaller teams, and one team was within reach of the summit.

Then exactly 50 years ago, a still, blue day arrived and that team made it to the summit. The group included Swiss mountaineers Peter Diener, Ernst Forrer and Albin Schelbert as well as Austrian Kurt Diemberger and two Sherpas.

“This was an expedition which, under Swiss organisation, was the first international ascent of an 8,000-metre peak,” Diemberger told the Swiss-based International Mountaineering and Climbing Federation (UIAA).

More than a week later, two other Swiss from the expedition, Hugo Weber and Michel Vaucher, also summited.

Eiselin hoped to summit as well but wasn’t surprised when it didn’t work out.

“For me the chances were quite small,” he says, “as I was the leader dealing with logistics.”

Looking back

Mountain enthusiasts and climbing luminaries will gather on May 13 in Nepal for a Golden Jubilee Celebration of the first Dhaulagiri ascent, put on by the Nepal Mountaineering Association.

“The successful summiting of Dhaulagiri in 1960 holds a great importance for the development of mountain tourism of Nepal globally,” Ang Tshering Sherpa, president of the association told the UIAA.

“It increased mountaineering activities in the Dhaulagiri area, with the uplift of the economic conditions of the people.”

Eiselin will not travel to Nepal for the celebrations. He will be getting together for coffee and remembrances with Diener.

The pull of the Himalaya isn’t what it used to be. “I stay closer to home now,” Eiselin says of his journeys into the mountains near Lucerne.

In a day before satellite phones and high-tech gear, he still feels pride in what the team accomplished.

“It was a very adventurous and dangerous expedition,” he says. But in all the climbing “we had not hurt a single person.”

Heidi Hagemeier in Lucerne, swissinfo.ch

In the years after the expedition, Max Eiselin did speaking tours and wrote a book about his experience, published as “The Ascent of Dhaulagiri” in English.

In his Lucerne Eiselin Sport store, he displays one of his knee-high boots from the trip, of Norwegian reindeer fur handmade in Italy.

Dhaulagiri, at 8,167 metres, is the seventh highest peak in the world. It’s name roughly means “white mountain” in Sanskrit.

Timeline (Wikipedia)

1950 – The peak is reconnoitered by the French, led by Maurice Herzog; however they did not see a feasible route so switched their objective to Annapurna, where they succeeded in making the first ascent of an 8,000m peak.

1953-1958 – Five expeditions attempt the North Face, or “Pear Buttress”, route.

1954 – J. O. M. Roberts and Sherpa Ang Nyima climb Putha Hiunchuli (the first successful major summit ascent in the range).

1959 – An Austrian expedition led by Fritz Moravecmakes the first attempt on the Northeast Ridge, which will become the first ascent route the following year.

1960 – The first ascent, achieved by a Swiss-led expedition.

1969 – Americans, led by Boyd Everett, attempt the Southeast Ridge; seven team members, including Everett, are killed.

1970 – The second ascent of Dhaulagiri, via the first-ascent route, by a Japanese expedition led by Tokufu Ohta and Shoji Imanari.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.