Climate threats: living in the shadow of a crumbling mountain

The COP26 summit aims to secure more ambitious climate action from participants. For some it’s already too late. At the popular Alpine resort of Kandersteg in the Bernese Oberland, villagers live with the threat of the nearby Spitzer Stein mountain tumbling down.

In the middle of an emerald-blue mountain lake, two tourists are struggling with a rowing boat. “You need to pull, not push,” shouts Robin from the shore.

The young boatman smiles and takes a long drag on his cigarette. Every year, thousands of people visit the spectacular Oeschinen lake and mountains above the village of Kandersteg. On this autumn morning, however, it is quiet. Not many are keen on hiring one of his boats or taking a dip in the icy water.

The early morning sun beats down on the majestic crown of 3,000-metre peaks. Suddenly, the sound of firecrackers echoes around the lake. Anxious tourists squint at plumes of dust rising above a distant flank.

“They are just small rocks coming down the Spitzer Stein,” Robin tells me. “My boss told me that we had some really big ones last night at 2am.”

Robin is not that concerned about the mountain hitting Oeschinen lake and wrecking his boat hire business. But he is worried about his village, Kandersteg, which would be directly in the path of any landslides, mudflows or flooding if the Spitzer Stein collapses.

A 30-second Google Earth animation (below) of Kandersteg and the Spitzer Stein.

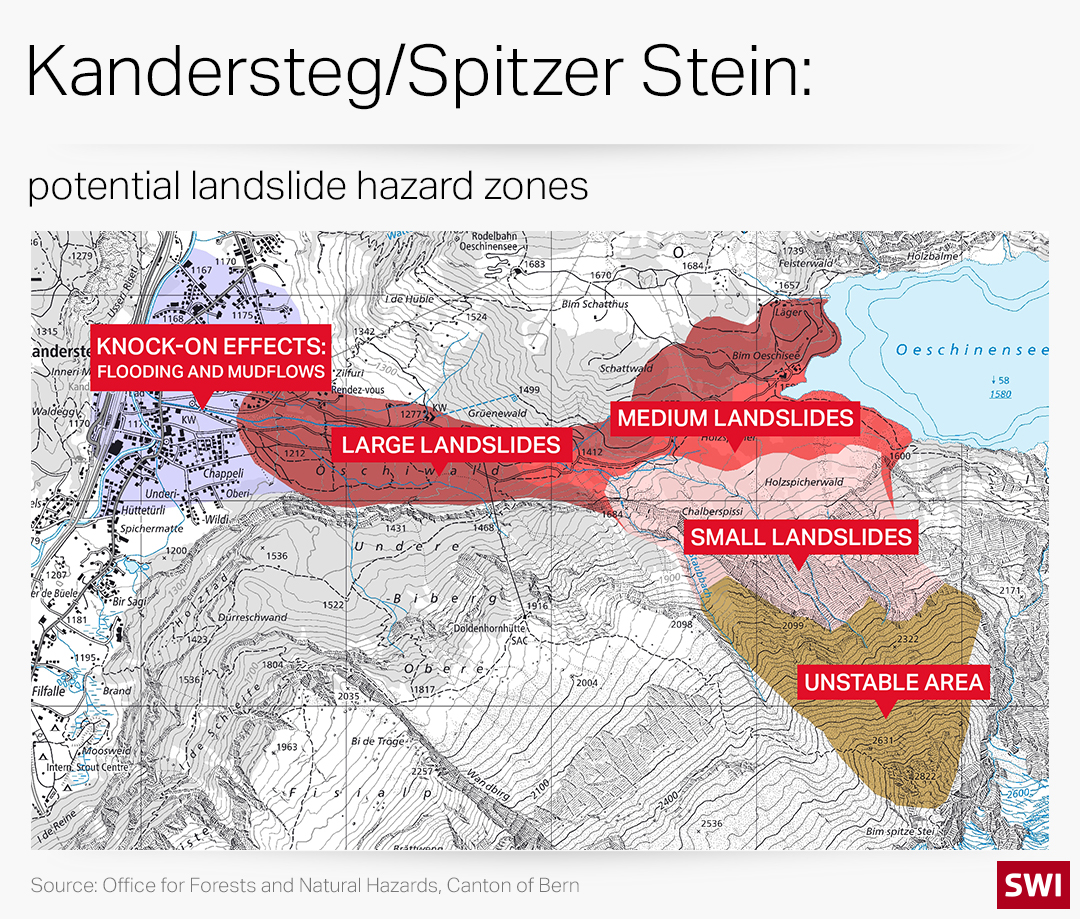

On the Toblerone-shaped Spitzer Stein (2,974m) disaster threatens. Five times as much rock as crashed down the Piz Cengalo mountain in 2017, devastating the village of Bondo and killing eight hikers, is on the move here. In a worst-case scenario, twenty million cubic metres of limestone and marl – the equivalent of eight pyramids – could come down with other debris and water, swamping Kandersteg and its residents.

Government officials, experts and campaigners are gathering in Glasgow, Scotland, from October 31 to November 12, for the 26th United Nations Conference on Climate Change (COP26). External linkThe aim of the summit is to negotiate more ambitious climate action from the nearly 200 countries that signed the 2015 Paris Agreement and agreed to limit the average temperature rise to well below 2 degrees Celsius and pursue efforts to limit it to 1.5C.

Switzerland is pursuing regulations that apply to all countries equally, focusing on three areas. Firstly, when a country reduces the greenhouse gas emissions it generates abroad, this reduction should only be counted once (rather than counting for both countries). Switzerland would also like to see investment increased, especially in climate protection measures in poorer nations. Finally, it will push for every country to develop strategies to become climate neutral by 2050.

Thawing permafrost

The climate crisis, the focus of the upcoming COP26 talks in Glasgow (see infobox), is slowly transforming the Swiss Alps. Temperatures are rising, glaciers are melting, and thawing permafrost is undermining the stability of mountain slopes. The Federal Office for the Environment estimates that 6-8% of Switzerland’s territory is unstable. Settlements below permafrost zones must increasingly expect landslides and mudflows in the years ahead.

Permafrost and the threats to Alpine regions will not be directly discussed at the COP26 meeting. But wider discussions about how communities adapt to devastating climate-related events will take place in Glasgow. Each country must present an “Adaptation Communication”, outlining its efforts, future plans and needs to adapt to the impact of climate change.

Switzerland’s long-term climate change adaptation strategyExternal link focuses on 12 priority areas, including managing increased risks of landslides, flooding, heatwaves and droughts.

The permafrost warming trendExternal link is visible across the Swiss Alps. Over the past 20 years, the Permos network has been monitoring and documenting the state of permafrost at 30 sites. Their measurements paint a bleak picture: permafrost temperatures have reached record levels in many high-altitude locations, as have the thickness of the active layer (the uppermost layer of the ground that thaws in summer) and the velocity of rock glaciers.

On the Spitzer Stein, rock falls are nothing new. But over the past decade, parts of the mountain have become more unstable. Fragile zones have extended, with large cracks appearing in the exposed bedrock. The causes are multiple. Thawing permafrostExternal link is thought to have exacerbated instabilities in the upper parts of the mountain flank. Higher temperatures have melted ice, allowing water to penetrate the underlying rock and contribute to the instability.

“Over the past three years we have really observed that the whole mountain is slowly melting,” says Robert Kenner, a permafrost expert at the Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research (WSL).

24-hour monitoring

The problem is that the instability is accelerating. The huge snowfall last winter and heavy rains this summer have increased the pace at which the Spitzer Stein is moving towards the valley, says Nils Hählen, head of canton Bern’s natural dangers department.

“The section that is sliding fastest is moving about 6-8 metres a year, which is an awful lot,” he explains. “We have looked out for similar cases in the Alps or elsewhere in the world, and it’s really hard to find similar displacement rates which are this high.”

Since 2018, Hählen and his team of experts have been closely watching the mountain, setting up a 24-hour observation network, which includes dozens of radars, GPS, cameras and precipitation measuring devices.

Hählen says it’s unlikely that all 20 million cubic metres will come down in one huge landslide. But over the next 5-10 years smaller rockfalls of between 1-8 million cubic metres could be possible.

He cautions: “In the worst case [a rock avalanche] could come quite close to the village, but not into the village. But we are concerned about secondary processes, such as debris flows.” A major landslide accompanied by heavy rain and mudflows could swamp parts of Kandersteg.

Protecting the village

With his red tie flapping in the wind, Kandersteg President René Maeder stands on the edge of a ten-metre-wide dam near the centre of the village. The 67-year-old official points to where a huge metal net will be strung across the dam to catch rocks and debris triggered by landslides on the Spitzer Stein. The protective structure, which is still being finalised, costs CHF11.2 million ($12 million).

“These are the protective measures that help with small to medium-sized events. But it’s impossible for such measures to protect against a highly unlikely large rockslide – impossible,” says Maeder, who was born in the village of 1,300 inhabitants.

Divided over the risks

So far, small rockfalls and alerts from geologists have resulted in the closure of hiking paths and sectors directly below the Spitzer Stein. Visitors seem unperturbed and hotel officials say there has been no noticeable impact on tourism.

Locals, meanwhile, are split over the dangers, with older inhabitants often more sceptical.

“I feel safe,” says elderly resident Doris Wandfluh. “We now have protection against the first big things if they come down. And if more follows, then perhaps there will be small damage, but I think residents will be protected in time, and any damage can be rebuilt.”

She says long-standing residents are more used to natural dangers like avalanches or storms than newcomers who are scared “as they have images of the Bondo disaster”.

YouTube video of the Piz Cengalo landslide in 2017 that hit the village of Bondo in canton Graubünden in south-eastern Switzerland.

The boatman Robin has doubts about the protective measures. “Some people say the dam is not a good plan, that it’s not wide enough at the bottom; I agree.”

“A building ban”

Thanks to the extensive hi-tech monitoring, a 48-hour warning will be given of any looming disaster. Residents should be able to evacuate in time, along with farm animals. But property and infrastructure could be damaged.

The rockslide dangers are a big headache for village president Maeder and many locals. Last autumn, the Bern authorities presented a new hazard map of Kandersteg that takes account of the new situation. Almost two-thirds of the village have been classified a red or orange danger area, even Maeder’s municipal office. No new buildings can be constructed and destroyed buildings cannot be rebuilt. Only small renovations and extensions are allowed.

“It’s basically a building ban. It’s a disaster for local business,” says Doris Wandfluh’s husband, Peter, who is an architect. Due to the hazard zoning, he recently had five building applications rejected, worth CHF3.5 million.

Some residents contacted Maeder last year to ask him to fight the new hazard zoning, which they say is exaggerated and imposed by building insurance firms. A decision on possible adaptations is expected in December.

“Today we have the tendency to want to secure everything. But you just can’t do that,” says the local president.

The residents of Kandersteg have lived with dangers for generations. The question remains: What kinds of risks are they willing to take?

“How much do we want to insure ourselves for an event that may only cause damage to property?” says Maeder.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!