This test could help Switzerland get back on track

Scientists agree that it will take many months to find a vaccine for the deadly new coronavirus. Yet politicians desperately need answers so citizens can return to their daily lives as soon as possible. A solution could lie with serological tests, which should be ready in Switzerland by the end of this month.

While we wait for a vaccine or treatment to fight Covid-19, scientists are developing tests to tell us how widespread the virus is. One option, in addition to screening, is the serological test.

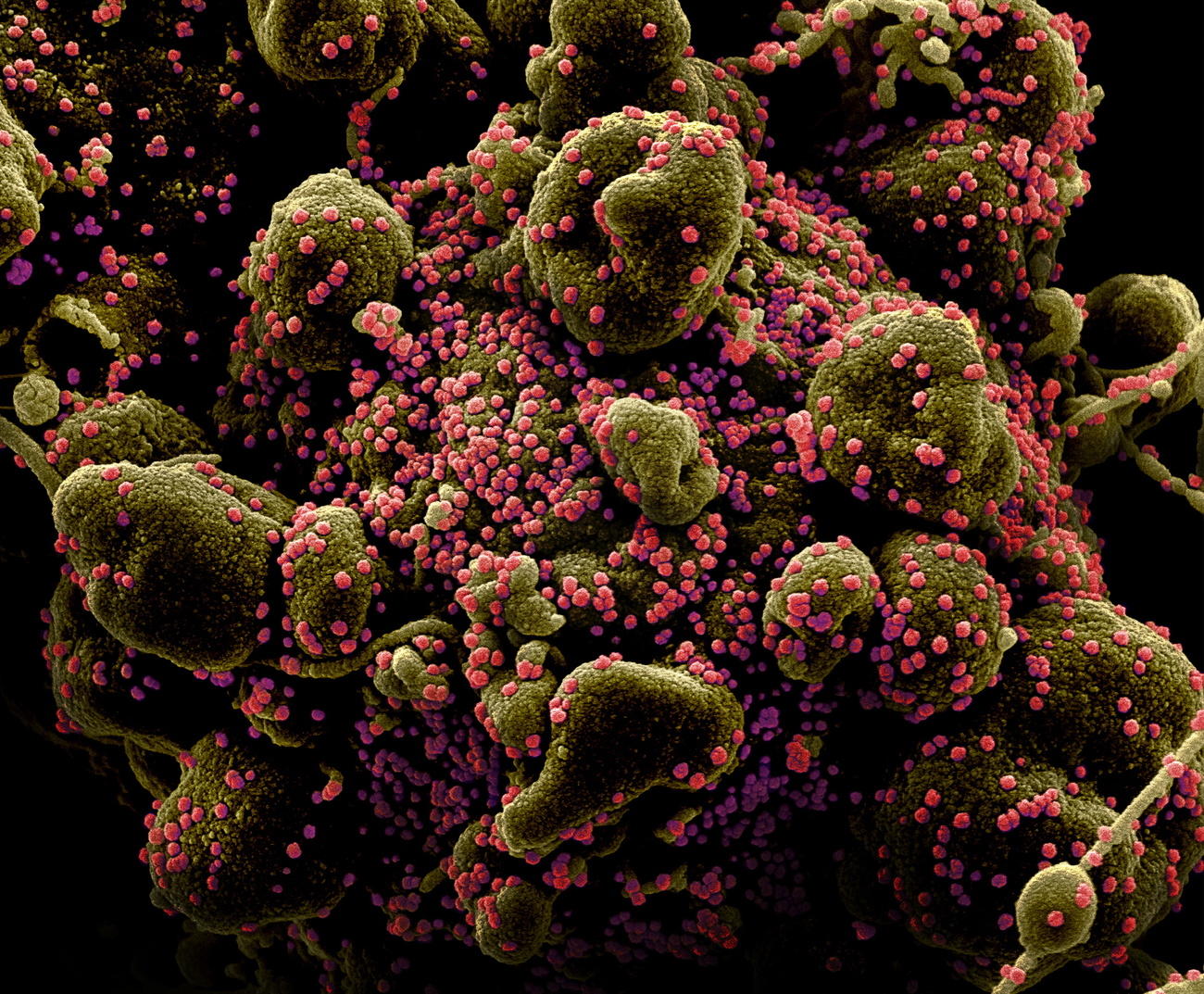

Our body fights infectious diseases thanks to our immune system. We produce antibodies in response to external agents, which then, hopefully, confront and eradicate them. After defeating an infectious disease, our body conserves a “memory” of the virus that attacked us so we can fight it better and faster if we are re-infected. This “memory” is the antibodies, and result is immunity – though in the case of Covid-19, it’s unclear how long that immunity lasts, as the government’s delegate on the Covid-19 pandemic Daniel Koch pointed out at a press conference on Thursday.

Serological testing can detect the presence of antibodies in the blood, in order to understand whether someone has already had Covid-19 and is immune. The results can help political decision-makers in the coming weeks and months as they analyse whether to continue to restrict individuals’ fundamental rights and when it’s safe to restart the country and economy.

More

What Swiss researchers are doing to beat Covid-19

‘Ready by the end of April’

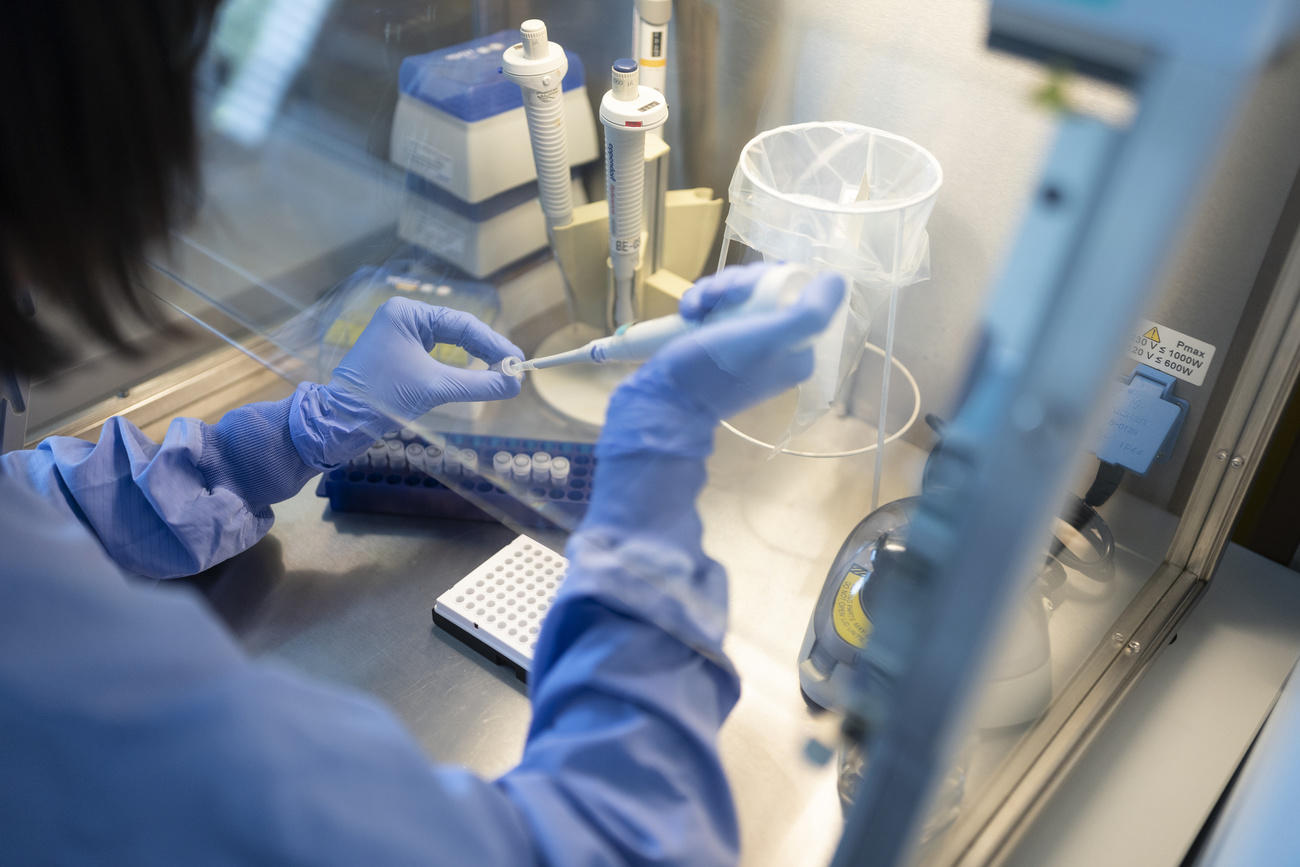

Serological tests are being developed in laboratories around the world in a race against time. Switzerland, which is at the forefront of biomedical research, is also investing resources to meet the challenge.

Various tests are already on the market, with the best ones being around 85-90% reliable. Others are currently announced as in development, including by pharma giant Roche, who said on Friday that it plans to have tests ready by early May, and then ramp up production to “high double-digit millions” by June.

Giuseppe Togni, scientific director of the Unilabs central laboratory in Coppet, canton Vaud, says the problem is the lack of data.

“Reliability is essential with this type of test. In our laboratories, we have currently managed to achieve a reliability of 99%. But this is not enough. We have to be 100% sure. It would be dangerous for anyone to feel safe based on a bad test.”

Togni, who heads up an international task force on the issue, expects that 100% reliability will be achieved in the coming weeks.

“Up until a few days ago, I would not have dared to suggest a timeframe,” he says. “But in view of the results, I am very confident. A reliable serological test will be ready by the end of April.” In the race to develop a test, Togni’s team is working with the universities of Geneva and Zurich.

More

Coronavirus: the situation in Switzerland

Protective antibodies?

Monitoring antibodies is essential, but scientists must also determine whether antibodies allow immunity to develop.

“The important thing is to know whether these antibodies are ‘neutralising’ or not,” explains Togni.

There are protective antibodies, which once developed mean you are immune to the disease, but there are also antibodies that are not protective, such as the ones that fight AIDS.

At present, it is still too early to label these antibodies as neutralising. “There are no definitive studies yet. Based on our experience, these antibodies should be protective because Covid-19 is very similar to other coronaviruses we already know,” says the researcher.

If Covid-19 does behave like those other viruses, it means those who have recovered from the infection will be protected regardless of whether they developed symptoms.

Science and policy

If we can identify people who are definitely immune, they could return to work, thereby minimising the risk of contagion.

“But this is not the question we should be asking ourselves; we have to ask ourselves who these tests are for,” argues Togni. “There is no point in testing the whole population. In Ticino, for example, according to reliable studies, between 5-10% of people are infected. It would make no sense to test everyone.”

So, who should be tested first? The researcher is convinced: “The healthcare staff. Then, people working in other essential professions. Then we can consider extending the tests to other sectors.”

But he warns against long-term testing discrimination. “During this period, we have witnessed great solidarity between people and especially between generations. If we start to choose who can and cannot take the test, this solidarity will inevitably disappear.”

The test itself is quick and easy to carry out, according to Giuseppe Togni of the Unilabs laboratory in Switzerland. A machine drips a blood sample into a solution containing the antigen from the virus, which is contained in a small test tube. After a short incubation period, the machine automatically reads the result: if there is a coloured reaction, it means the sample is “positive” and antibodies are present in the sample. The machine can carry out 400 tests per hour automatically and, if necessary, operate continuously 24 hours a day.

Translated from French by Simon Bradley

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.