Covid-19 testing: Switzerland did not prepare enough for the second wave

After emerging relatively unscathed from Covid-19 in the spring, the country was hit hard by a second wave of the virus in autumn. One of the reasons was insufficient testing.

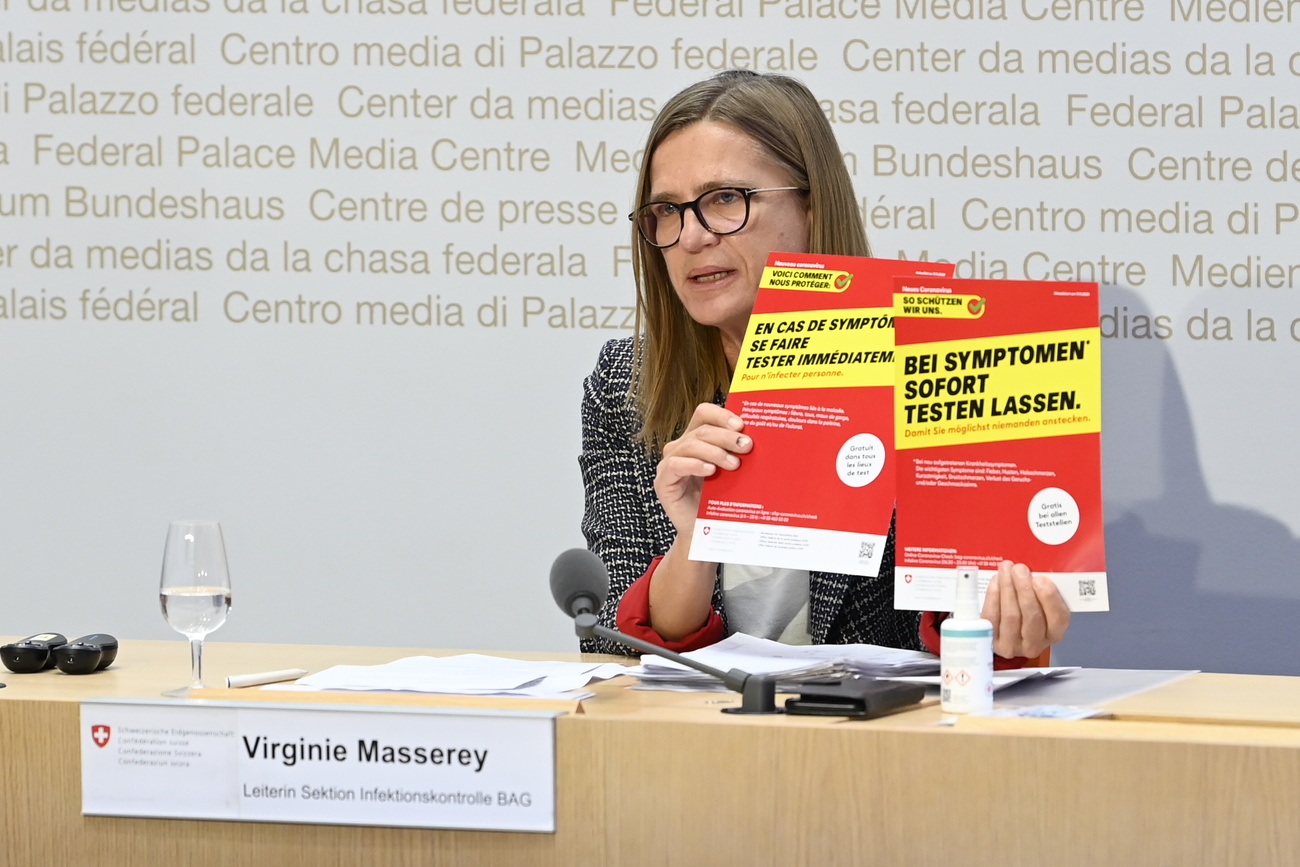

Testing should be done as “widely as possible” in order to respond rapidly to any new increase in the number of new coronavirus cases, declared Switzerland’s governing Federal Council on June 24. The costs of all Covid testing across the country would be covered by the government, it added. This was aimed at “simplifying the system” and avoiding the situation where people are reluctant to get themselves tested if they have to “bear the costs themselves”.

Tests were at the heart of Switzerland’s so-called “TTIQ strategy” – testing, tracing, isolation and quarantine – which was adopted by parliament to combat Covid-19 and limit the impact of a second wave in Switzerland.

Five months later, it is clear that this strategy has failed. Access to tests has not really been simplified, nor made free of charge for everyone, and the authorities have been slow to increase their availability.

Meanwhile, the second wave has hit hard. In the first three weeks of November Swiss cantons – especially the French-speaking ones, and Geneva and Fribourg in particular – regularly featured among the top European regions most affected by the pandemic.

Restrictive access criteria

In an information sheet dated September 18, the Federal Office of Public Health outlined the three criteria for a “free” screening test: you must have Covid-19 symptoms, have received a contact notification from the SwissCovid smartphone app, or have received a request from the cantonal doctor’s office after having been “in close contact” with an infected person in quarantine.

Switzerland has applied much more restrictive criteria than at least two of its large neighbours. In Germany, tests are available free of charge for all asymptomatic persons who have been in close or distant contact with a positive case, for inhabitants of an area at high risk of contamination or for persons returning from a country at risk. In France, screening is fully covered for all people registered with the health insurance system, even for people without symptoms and without a medical prescription, especially those who must test negative when travelling abroad.

Screening bottleneck

The Swiss federal government insists that the TTIQ strategy is only a recommendation by the public health office and that “its implementation is the responsibility of the cantons”, which remain free to devise their own strategies. In Geneva, for example, people who wish to have the costs of the test covered must go to one of the six screening centres commissioned by the cantonal authorities. But at the Geneva University Hospital (HUG), some patients had to wait up to 48 hours for an appointment this autumn.

“From September onwards, we saw a growing number of patients until the peak in mid-November,” explained Dr. Frédérique Jacquerioz, deputy physician in charge of the Covid test centres for adults at the Geneva University Hospital. “To better guide them, we have set up a screening procedure on our website: before an appointment can be made, the patient has to fill in an online questionnaire that will enable us to determine whether he or she needs a medical consultation and to which centre we will send him or her for testing.”

However, as the hospital has been busy, many people have had to resort to private laboratories and incur costs of more than CHF100 (around $110) to get tested.

Too little, too late?

At the beginning of October, the HUG opened a new test centre in response to the urgent situation in Geneva. But looking back, it’s clear that Switzerland “didn’t test the population enough” this summer, said Professor Didier Pittet, head of the department for prevention and control of infections at the same hospital. Moreover, it did not see “the increase in the level of endemicity of the virus” coming.

According to data from Oxford University published by Swiss public broadcaster RTS, between July 11 and August 29, 5.3 people out of 1,000 were tested each week on average in Switzerland, compared to 8 in France and Germany, and even 17.6 in the United States. Pittet refers to a certain “easing off” by the authorities and the Swiss population over summer.

This feeling is shared by Arthur Germain, co-founder of OneDoc, the first Swiss platform for online medical appointments.

“We were all surprised by the speed of the second wave. At the beginning of summer, we thought that most of the coronavirus pandemic was behind us,” he said. “But at the end of summer, when the big hospitals started contacting us to help them set up online appointments for PCR testing, we soon saw the evidence.”

Today, OneDoc offers more than 50 screening centres for PCR testing throughout Switzerland. By the end of November, more than 105,000 appointments had been booked online.

“We could have anticipated things better, that’s for sure, but I think we managed to react fairly quickly,” said Germain.

Slow rollout of rapid tests

What about rapid antigen tests? On October 28, the Federal Council announced with great fanfare that antigen tests would be available in Swiss pharmacies as early as the following week. At the beginning of November, swissinfo.ch visited several pharmacies in Geneva and confirmed that none of them had been able to meet public demand for the tests.

“We received a lot of calls the day after the press conference, but we hadn’t been forewarned at all,” said Julia, a pharmacy assistant in Geneva. “In the following days, we received a message from the cantonal pharmacist inviting us to sign up on a waiting list to obtain the equipment and training needed to carry out these tests.”

Today, her pharmacy still hasn’t received any further information about antigen tests. The cantonal pharmacist, meanwhile, affirms that that “pharmacies will receive them progressively” from the end of November.

At the federal level, the situation is no better. As of mid-November, only four pharmacies in the entire country were offering the OneDoc rapid test.

The situation falls far short of the target of 50,000 tests per day set by Health Minister Alain Berset. Once again Switzerland is lagging behind its neighbours. In France, the Trade Union of Community Pharmacists guarantees the availability of antigen tests in over half of the country’s pharmacies. Germany, for its part, began offering this service in its pharmacies and laboratories at the end of September.

Although rapid tests are less reliable, they are nevertheless a valuable tool in the fight against Covid-19, as a complement to PCR tests. They can significantly increase testing capacity and break the chains of infection quickly, especially in the context of mass screening campaigns, such as the one conducted on a large scale in Slovakia in early November.

“Today, screening centres and pharmacies in Switzerland have understood this,” declared Germain. “They are preparing to be ready to respond to such a demand.”

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!