How science is helping unearth ancient submerged Alpine settlements

Improved research methods have helped archaeologists learn much more about the civilizations that lived in stilt-house villages in and around the Alps thousands of years ago. Researchers continue to be surprised by new findings and what remains to be uncovered.

The early morning sunshine slowly burns through the shimmering mist on Lake Biel in western Switzerland. From a wooden platform, a group of divers surveys the chalky emerald waters below.

“Winter is the best time to dive as it’s clear; there are no boats or vegetation,” says Lukas Schärer, head of canton Bern’s underwater archaeological diving service.

Today, the lakeshore is crisscrossed with roads, building complexes and vineyards. Between 5000 BC and 50O BC, this part of Switzerland was dotted with pile dwelling (stilt-house) villages, home to hundreds of people who fished and farmed in a region that remains one of the Alpine country’s agricultural hubs. Schärer and his team are responsible for researching the now-submerged pile dwelling villages and other archaeological sites in the region.

Their base is the village of Sutz-Lattrigen on the southern shore of Lake Biel, home to many Neolithic and Bronze-Age archaeological sites. It was there that in 2007 archaeologists discovered traces of Switzerland’s oldest known building, a pile dwelling dated to 3863 BC.

New discoveries continue on a regular basis. Just this year, scientists reported a spectacular underwater find in Lake Lucerne, about 100 kilometres to the east. There, divers uncovered a stilt-house village and artefacts that showed the region had been populated 2,000 years before anyone had previously thought.

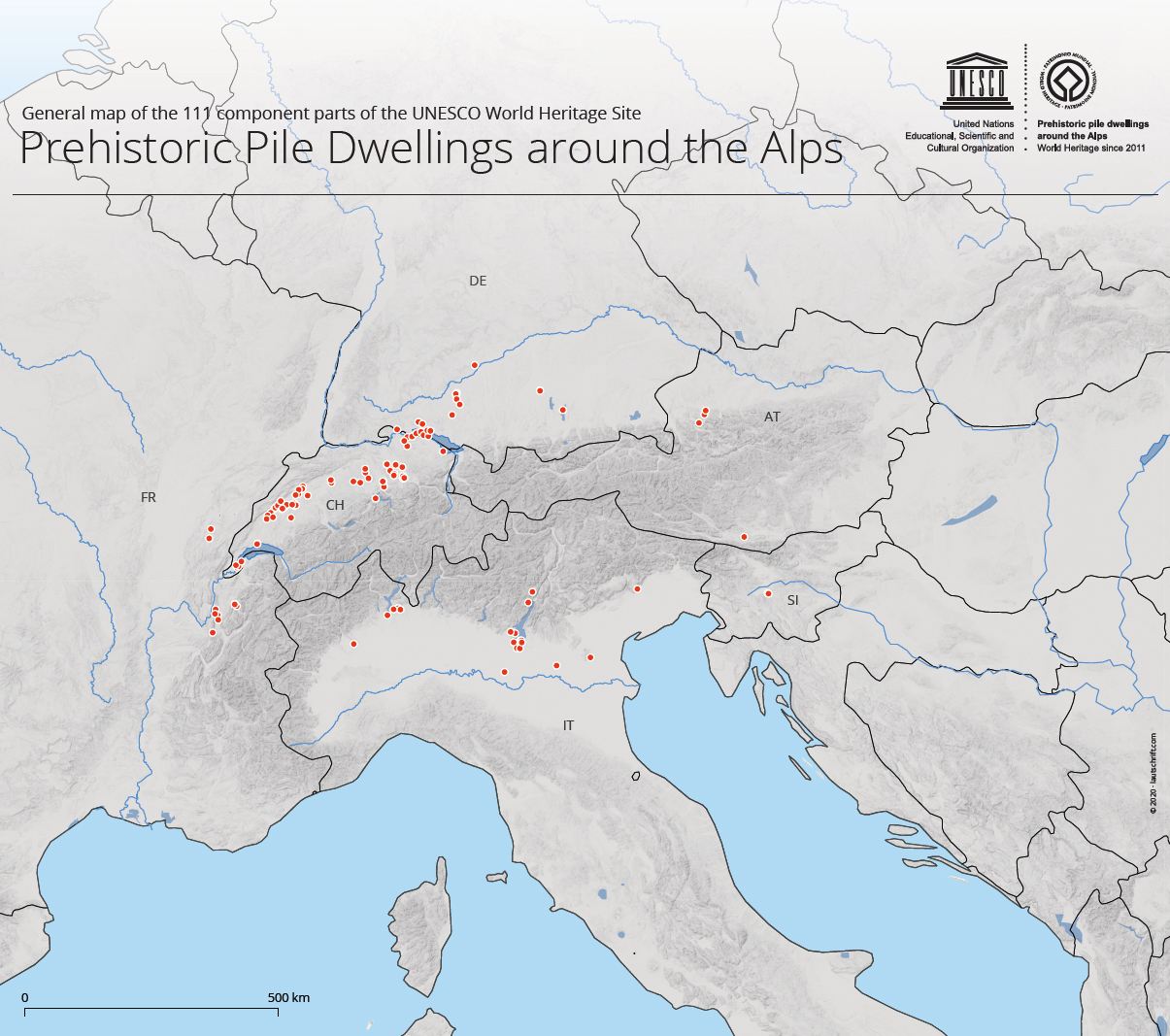

To date, almost 1,000 pile dwelling sites have been documented in lakes, rivers and bogs in six countries around the Alpine region (Switzerland, Germany, Italy, France, Austria, and Slovenia). June 27 marks ten years since the United Nations culture agency UNESCO attributed World Heritage status to 111 of the sitesExternal link (see infobox).

June 27 marks the tenth anniversary of prehistoric lakeside pile dwellings in Alpine countriesExternal link – including in Switzerland – being given UNESCO World Heritage Site status.

In 2011, 111 of the most important sites in Switzerland, France, Germany, Italy, Austria, and Slovenia countries were given the prestigious heritage label. Of these, 56 are in SwitzerlandExternal link. UNESCO describes the groupExternal link of dwellings as “one of the most important sources for the study of early agrarian societies in the region”. “Prehistoric Pile Dwellings around the Alps”.

Tough work

Underwater archaeology, which developed from the 1960s thanks to the invention of the diving regulator, is now a well-established technique and an essential part of research into lakeside settlements. Advances in research techniques have led to more breakthroughs, but the work can be tough.

“It’s physically demanding, as you have to carry a lot of weight even to dive in shallow water,” says Schärer. “And we’re always out in every season. It can be difficult at times, especially if it’s below-zero in winter or if it’s raining all day.”

Even seeing underwater can be challenging. To maintain good visibility, divers use an artificial current. Suction pipes are also deployed to expose and excavate sites.

Their work varies from place to place. Much of the time is spent documenting and monitoring sites. Whereas most of the early work was done by hand, they now use high-tech devices like side-scan sonars, multibeam echosounders, underwater digital cameras and drones.

When sites are at risk of erosion, divers employ other methods to preserve the fragile archaeological layers. One effective technique involves covering the lakebed and wooden piles with natural textiles, such as coconut fibre, weighed down by gravel.

Hidden treasures

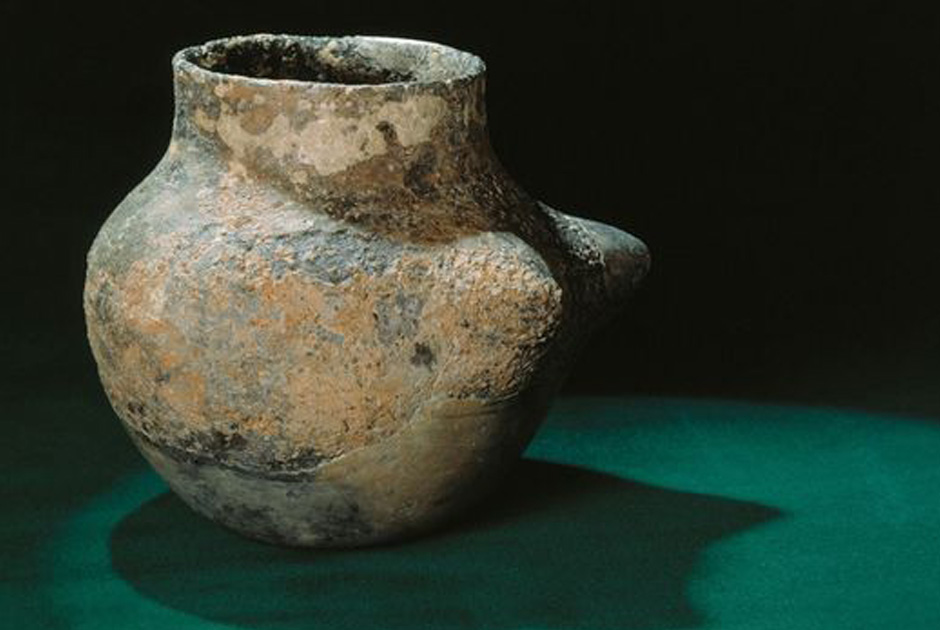

Preserved under water, sand and mud, prehistoric ancestors have left behind an invaluable record of their lives, which has survived virtually intact for years. Divers continue to find unique objects, including one of the oldest wheels in the world, earthenware pots, dugouts, clothes, and even ancient chewing gum and bread.

“We have a management plan for the UNESCO sites; we don’t search them entirely,” explains Regine Stapfer, deputy head of canton Bern’s archaeological service. “The aim is to leave them and protect them as much as possible but if there are parts that have strongly eroded, it’s best to carry out searches.”

At a nearby site at Täuffelen, the erosion has gone too far. Schärer and his team are systematically excavating the site, with two divers covering 15 square metres a day. But if there are thick layers of sediment, they can only manage to clear and examine about one square metre a day.

Measuring tree rings

One of archaeologists’ most central questions revolves around the age of the settlements and the objects they find. That makes the collection of wood samples one of divers’ most essential tasks, because they can use dendrochronology – the technique of dating by tree rings – to estimate age.

On the lake platform, one of the diving team cuts wooden lake piles into thick circular slices. These will be passed to colleagues in the dendrochronology laboratory at Sutz-Lattrigen for further analysis.

Tree-ring dating has made huge advances over the past 30 years, say scientists. The method is now extremely accurate thanks to extensive sequencing of certain tree species and detailed local reference chronologies that allow experts to go far back in time. European oak, for example, can be traced back 10,000 years.

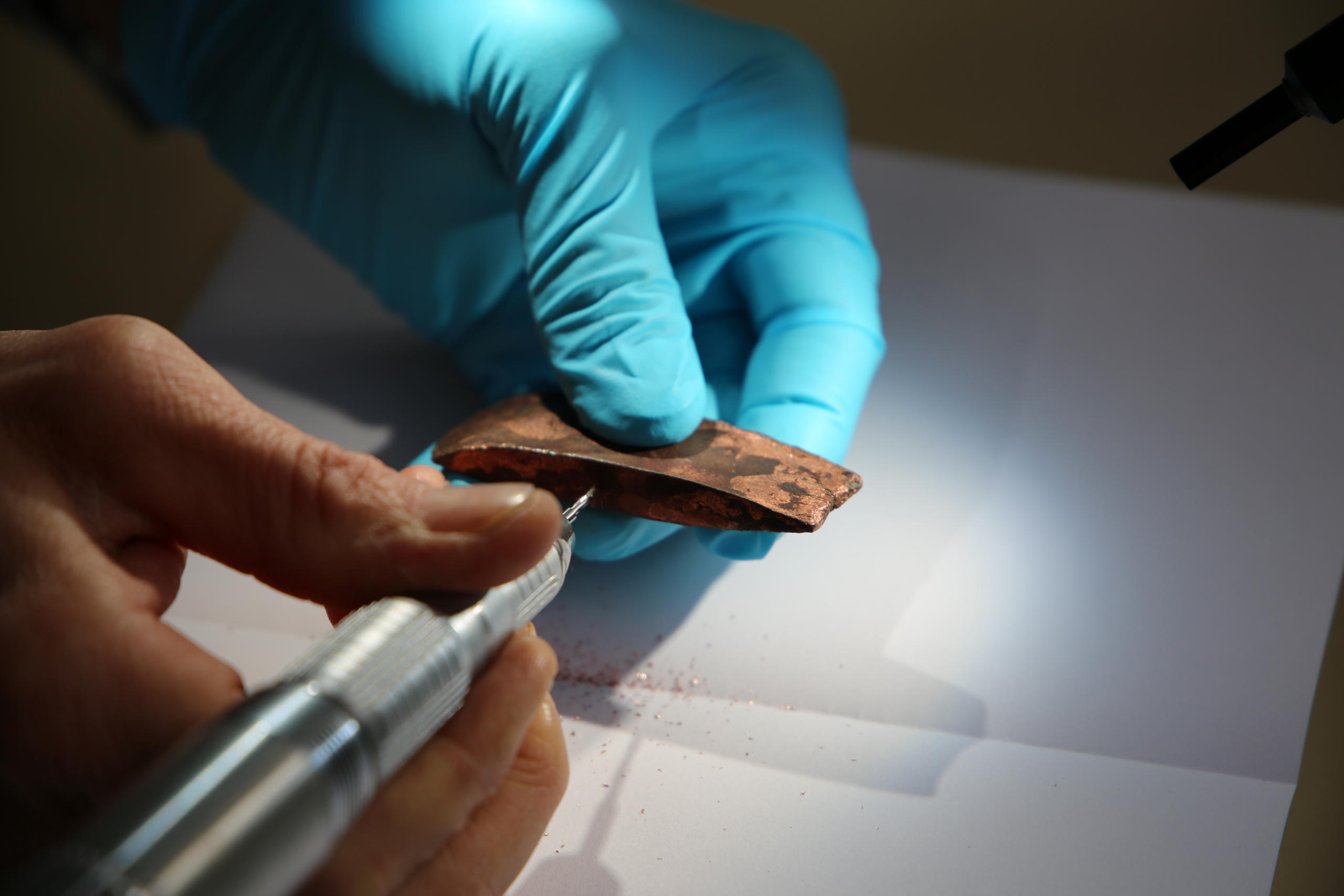

At first glance, dating wood seems a fairly simple process. A sample is prepared by removing a thin top layer with a razor. Chalk is then applied to make the rings stand out under a microscope. But later technology takes over: a computer programme plots the rings on a graph and compares the sequence against standard references.

Building the puzzle

Thanks to dendrochronology, archaeologists can now determine the exact year a specific tree was felled. By cross-checking that against underwater photos of wood piles and other finds, the researchers can slowly build a picture of a village, how it was settled and how the local forest was used.

Yet piecing together pile dwelling puzzles is complex. Settlements often existed for relatively short periods, and future generations often resettled years later in the exact same location by the lake.

“Sometimes you end up with nine villages, one on top of each other,” says Matthias Bolliger, head of the dendrochronology laboratory at Sutz-Lattrigen.

On his screen, dozens of different coloured dots – each representing an underwater pile – are arranged in the shape of a rectangular settlement he is studying.

‘Suddenly, there is something’

Sophisticated research techniques have also revealed much more about how people living in Switzerland’s pile dwellings around 4300 BC grew crops and kept animals. We also know more about how they hunted and gathered wild plants, how they used lakes to fish and as transport routes, and how they managed woodland sustainably.

Stapfer points out that these civilizations were much more advanced than we give them credit for.

“They had a really good idea how to use different natural materials to make clothes and other items,” she says. Neolithic hunters used materials like birch bark to make rain-resistant arrow cases and other materials, not unlike how we invented Gore-Tex. Her team found a shoe in Sutz-Lattrigen made of bast fibres, which dates to 2700 BC.

But there are still many unknowns about the people who lived in pile dwellings, say archaeologists.

“We find the materials they used, the tools and bowls, but we have very little information about their lives, how they were organised, what beliefs they had,” says Schärer.

Divers sometimes come across fish or animal bones, but it is rare that they find human remains or objects related to burials.

“It’s not clear if they buried their people in another special place or if they burned them and scattered their ashes on the lake,” says Stapfer.

If the recent spectacular pile dwelling finds in Switzerland’s Lake Thun and Lake Lucerne are anything to go by, there is much more to discover under the waves, say scientists.

“These are places that were looked at perhaps 10, 20, 30 years ago,” says Andreas Mäder, head of Zurich’s underwater archaeology service. “At the time we said, ‘there’s nothing there’. Suddenly, there is something. This simply means that the lakebed has eroded and that new finds have come to light.”

Edited by Veronica De Vore

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!