Cornelius Gurlitt’s moral legacy

All Cornelius Gurlitt wanted was to live in peace with the art he had inherited from his father. But the last years of his reclusive life were to prove anything but peaceful, writes Berlin-based arts journalist, Catherine Hickley.

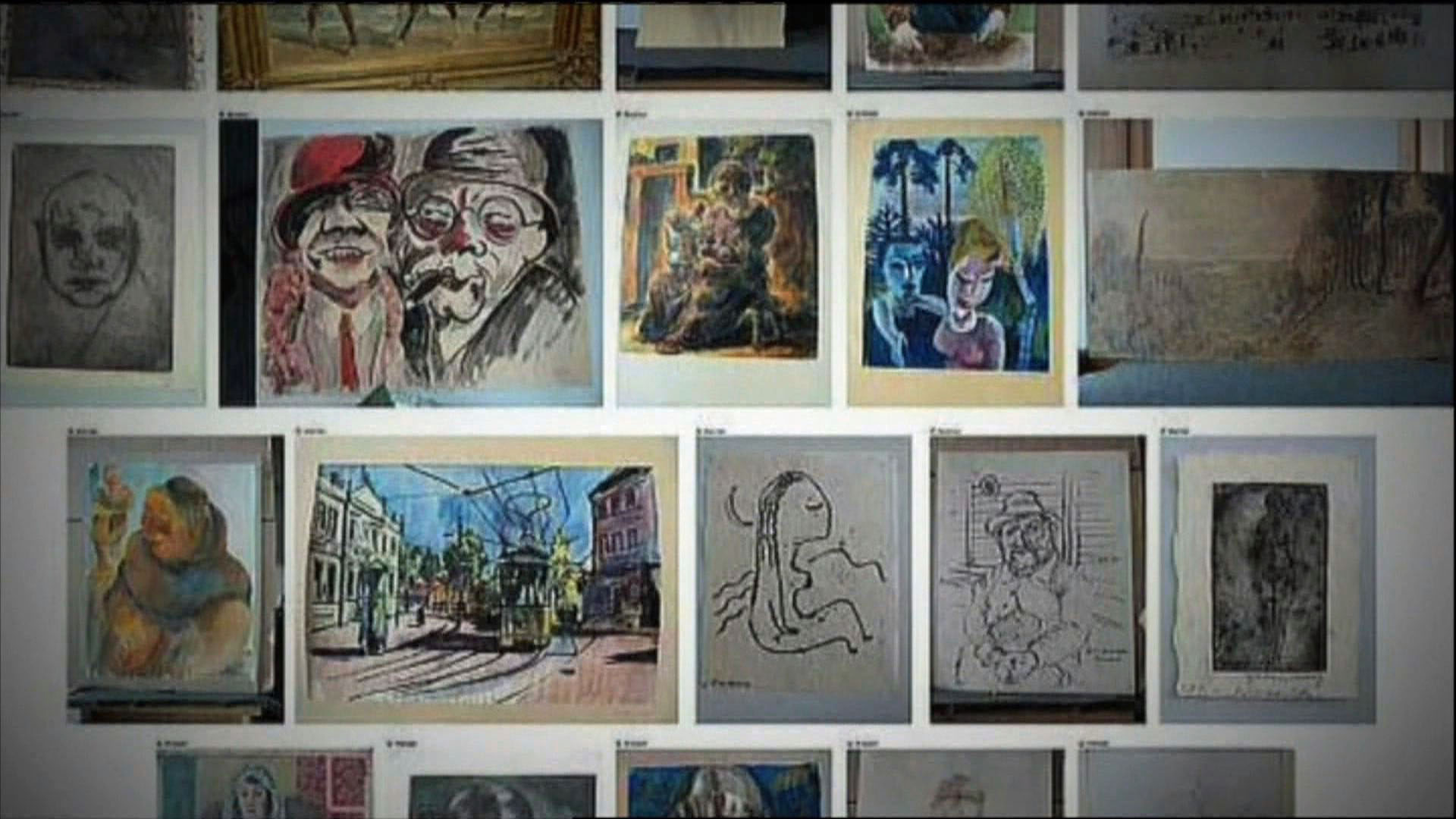

Gurlitt became the subject of a criminal investigation, his apartment was raided and his pictures were taken away. Bereft and bewildered, he was besieged by journalists and overwhelmed by claims from the heirs of Jewish collectors who were persecuted and expropriated more than 70 years ago.

He became a polarising figure in a complex legal debate, sparked disbelief, outrage and sympathy worldwide, and hammered home to Germany the ongoing national responsibility to address the darkest chapter of its history. Considering he rarely left his apartment, Gurlitt made quite an impact.

Then from his hospital bed in the last weeks of his life, under an enormous amount of public pressure, Gurlitt set a moral benchmark that many museum directors, art dealers and private collectors would do well to follow.

He pledged to apply the international Washington Principles in addressing the heirs’ claims. These non-binding guidelines on handling Nazi-looted art in public collections were endorsed in 1998 by 44 governments, including Germany and Switzerland.

Yet all too often, they are ignored or bypassed by museums and politicians. Private collectors, with the notable exception of Gurlitt, are not bound by them at all.

Catherine Hickley was the arts correspondent for Bloomberg News in Berlin for eight years, where she reported regularly on Nazi-looted art and restitution. She is now writing a book about the Gurlitt collection.

The principles state that “every effort should be made to publicise art that is found to have been confiscated by the Nazis.” The German government (admittedly without Gurlitt’s consent) published details of the artworks with dubious provenance seized in his Munich apartment.

Yet only a few museums have done this and some of them very half-heartedly. Without knowing what lurks in the depots, heirs have little chance of finding artworks stolen from their families decades ago. Tracking down art in private collections is even harder.

Gurlitt’s archive – the correspondence and business books he inherited from his father – is accessible to the government task force investigating the provenance of his collection.

The art world in general is notoriously opaque. Many dealers and even museums protect their files from foreign eyes. Before his late change of heart, Gurlitt sold artworks over the years that we may never find out about.

The Bernese dealer Galerie Kornfeld purchased four works from him in 1990. Eberhard Kornfeld said they were pictures seized by the Nazis from German museums and therefore not subject to restitution claims.

But this is impossible to verify independently as he has volunteered no details about them. I wrote to him asking for information for my book, and he responded by saying he couldn’t provide answers for at least six months because he was too busy with auctions and he didn’t know whether the documentation was still in the company files.

By promising “just and fair solutions” including restitution to the heirs, Gurlitt pledged to do more than many public institutions.

Several museums are holding on to Nazi-looted art and refusing to negotiate with the heirs. The city of Munich, for example, has been waging a byzantine court battle over decades against the heirs of Sophie Lissitzky-Kueppers to keep hold of a Paul Klee painting that was seized by the Nazis.

In violation of the spirit of the Washington Principles, it has tried to apply legal statutes of limitations and technical defences to foil the heirs.

swissinfo.ch has begun publishing op-ed articles by contributors writing on a wide range of topics – Swiss issues or those that impact Switzerland. Over time, the selection of articles will present a diversity of opinions designed to enrich the debate on the issues discussed.

For the families who were robbed, failure to address the crimes of the Nazis perpetuates the injustice they suffered. No one can bring back the millions who died in the Holocaust. Looted art, though, can still be returned to the families it was stolen from.

Those thefts are among the last Nazi injustices that can still be redressed – Ronald Lauder, the president of the World Jewish Congress, has called the missing paintings “the last prisoners of World War II.”

David Toren, who claims the Max Liebermann painting of two horsemen on a beach found in Gurlitt’s apartment, is 89. He was lucky to escape Nazi Germany as a child. His parents were both gassed at Auschwitz and the only heirloom he possesses was a family photograph that he took with him.

Toren remembers the Liebermann painting hanging in his uncle’s home, and has been searching for it for 70 years. If he is to reap any benefit from its return, it needs to happen soon. Otherwise this could be another instance where justice delayed is justice denied.

Matthias Frehner, the director of the Kunstmuseum, has said it may take as long as six months for the museum to decide whether it will even accept Gurlitt’s inheritance with all the responsibility it carries. As a foundation financed with both private and public funds, is it beholden to the Washington Principles? Does the agreement Gurlitt reached with the Bavarian and German governments transfer to his heirs?

What has so far emerged about the Gurlitts and Switzerland is not necessarily confidence-inspiring for the heirs of Jewish collectors persecuted by the Nazis.

Many of them will remember the dormant accounts and Nazi gold in Swiss banks exposed in the 1990s. As well as providing banking services for the Nazis, Switzerland was an art-trade hub. Theodor Fischer’s Lucerne auction house staged the biggest sale of art seized as “degenerate” from German museums.

Hildebrand Gurlitt, a dealer who bought and sold art for the Nazi regime, purchased regularly from Fischer, who counted him as a friend. Fifty years later, Hildebrand’s son Cornelius sold unidentified art via Galerie Kornfeld, which has close ties with the Kunstmuseum. Cornelius also rented two safety deposit boxes at UBS in Zurich. We don’t know what they contained.

Frehner has promised that the Kunstmuseum will handle its heavy inheritance responsibly. The world will be watching to see whether the museum perpetuates Cornelius Gurlitt’s last-minute moral legacy as well as preserving his art.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.