Wettstein – the first Swiss diplomat had the city of Basel in mind

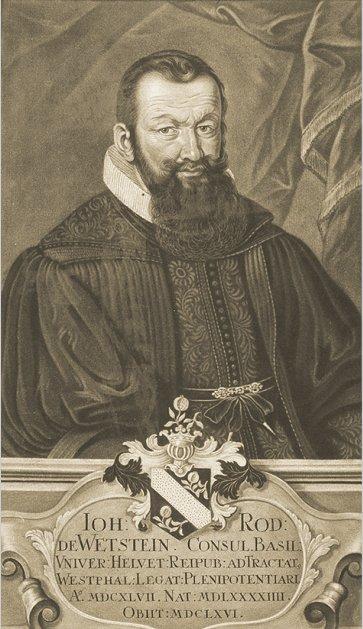

It was 370 years ago that the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) ended with the peace conference at Münster, Westphalia. Johann Rudolf Wettstein was the man of the hour for the Swiss Confederacy.

Although Switzerland had largely been spared in the hostilities, there was a unique opportunity at the negotiating table to get clarity about things that Swiss are still concerned about: trade and the jurisdiction of foreign courts, power politics and the international status of the Confederacy. This was a herculean task that required a clever diplomat.

In 2018 we can commemorate two epoch-making peace treaties: the treaty of Versailles ending the First World War (1914-1918), and the treaty of Westphalia ending the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648).

While Versailles has gone down in history as a miscalculation with eventually disastrous results, the Peace of Westphalia is considered today as one of the most useful and long-lasting agreements in European history.

swissinfo.ch asked Andreas WürglerExternal link, professor of medieval and early modern Swiss history at Geneva University about the war, the peace, and the great Swiss negotiator Johann Rudolf Wettstein, who was a product of those troubled times.

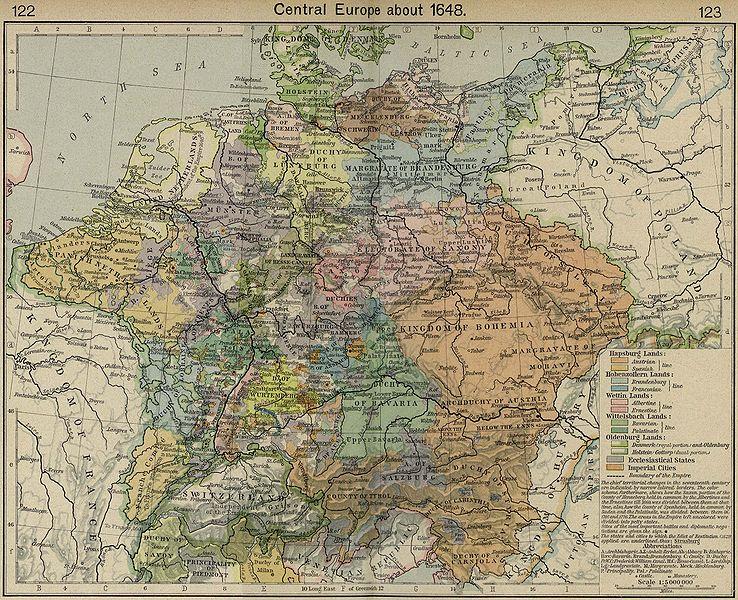

For 17th-century Europe the Thirty Years’ War was every bit as destructive as the Great War was for a later generation of Europeans. In some regions, war, hunger and plague killed off half the population.

It took 30 years and millions of war dead to put an end to this destructiveness. Religious war was replaced by the ‘Westphalian system’.

This arrangement meant not just peace, but a real paradigm shift in Europe, Würgler says. Up till 1648 there was a clear hierarchy of power relations in central Europe: the Pope and the Emperor on top, then the kings, reigning princes and nobles, and at the bottom the peasantry.

Switzerland still officially belonged to the Holy Roman Empire, and so was part of this hierarchy rather than being a fully independent state – unlike France, say. The Confederacy was just a loose alliance of cantons that looked out for themselves and each other.

Chequered career

This was the world into which Johann Rudolf Wettstein was born on October 27,1594. He studied for a time at the university in Basel, took further legal training in Geneva, served for a time as a mercenary in Italy, and then, as a civic official at home in Basel, he worked his way up to be mayor of the city.

“In his biography there were all sorts of useful experiences needed in the 17th. century if someone was to fulfil a diplomatic role – although Wettstein was really just a social upstart,” says Würgler.

In 1646, when Wettstein, now aged 52, travelled to Münster for the peace conference, he was mainly concerned about his own city’s welfare. At this early stage of the game, Wettstein saw the peace negotiations as just an opportunity to represent the interests of Basel, Würgler believes.

To be precise, Wettstein was hoping to resolve the century-old dispute about jurisdiction over Basel merchants.

Basel was one of the few cantons which had not yet freed itself from the jurisdiction of the high court of the Holy Roman Empire. There Basel merchants were frequently sued by German competitors. Their goods were confiscated. “That was a burning issue for a merchant city,” notes Würgler.

No common position

As regards the Thirty Years’ War, it had become clear early on that the members of the Swiss Confederacy were not going to be able to agree on a common position.

Particular cantons were not keen on getting involved in the war. For then, Catholics and Protestants would not just be fighting abroad as mercenaries as they often did, but they would be fighting each other on the home front too.

The conflict between France and the Hapsburgs over control of what is today Graubünden was a graphic example to the other cantons how destructive this war could get.

So the Confederacy as a whole took no part in the bloodletting. But there was still nothing like a uniform Swiss policy of neutrality:

“There were groups that favoured staying out of the fighting, because the Confederacy would lose all influence in Europe if it fell prey to an internal religious war. But there were also groups that wanted to get involved.

“The Zurich clergy for example wanted an alliance with Protestant Sweden. Catholic cantons had already signed an alliance with Spain at the end of the 16th century in case of a Protestant attack. The cantons were blocking each other, one side in fear of the other.”

Switzerland was not a party to the major conflict, but it was profiting from trade in military supplies and from the export of foodstuffs.

“Due to its favourable situation as a country unaffected by war in the midst of countries at war with one another, Switzerland’s trade and agriculture were enjoying something of a boom,” says Würgler.

New order in Europe

In February 1647, at his own request, Wettstein secured a mandate to negotiate for the whole Confederacy.

What he brought back from Münster was the ‘Exemption’, an exceptional deal for Switzerland.

More

The day Switzerland became neutral

This in fact meant a political divorce from the Holy Roman Empire. De jure, the Confederacy was now a sovereign union of states. Finally, Wettstein travelled to Vienna in 1650 to resolve the ongoing trade dispute with the Emperor and put a stop to the bothersome suits against Basel merchants.

Wettstein had now achieved his original goal. But he had also done much more: Switzerland was now a sovereign state, free from interference from the Emperor and his law-courts.

Following the Peace of Westphalia, the ruling principle was ‘equality of states’, and the beginning of what we now call international law. The status of ‘sovereign state’ was granted to any and every political formation that was able to maintain its independence economically and militarily.

“International law defines states primarily as sovereign subjects of equal status. Diplomats shake hands instead of kowtowing to each other. But how states actually behave towards one another, was then, and is still today, a matter of power relations,” Würgler sums up.

For this historian, the issue of Swiss sovereignty is closely bound up with the issue of neutrality. Switzerland had to reposition itself as a small state.

Neutrality was understood well into the 17th century as a mere temporary position, and not an all-embracing doctrine as public opinion sees it today. Only in the 1670s did the Swiss begin to invoke their neutrality in time of war and thus to add value to a concept which had enjoyed little respect hitherto.

Wettstein – a modern hero?

Neutrality, sovereignty, religious pluralism: all these Swiss achievements emerged from disputes and discussions lasting centuries. Wettstein’s success in Münster was an important milestone along the way.

“He was all alone in Münster, and as the only ‘diplomat’ he represented the entire Confederacy,” Würgler notes.

“His great achievement was that he soon realised what was really at stake in this peace conference.” He was able to read the signs of the times – the coming of the Westphalian system.

The Confederacy, on the other hand, took a long time to give Wettstein’s achievement any recognition.

To begin with, it took nearly 50 years for all the cantons to realise that they were ‘exempt’ – that is, released – from the dictates of the Holy Roman Emperor. On the other hand, Wettstein lost a lot of sympathy at home when as mayor of Basel he took a hard line in dealing with the insurgents in the peasant revolt of 1653, Würgler explains.

“Again, though Wettstein himself supported religious pluralism within the Confederacy, Swiss national heroes have tended to be from before the great division – think of Tell, Winkelried and St Nicholas of Flüe. Wettstein as a Protestant could not really be a hero for Swiss Catholics.”

Only with the Enlightenment, and then the foundation of a federal republic in 1848 and the resulting religious compromise, did Switzerland learn to ascribe importance to Wettstein and give him his due.

In 1881 a new bridge in Basel was named after him – the landmark Wettstein Bridge.

Translated from German by Terence MacNamee

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.