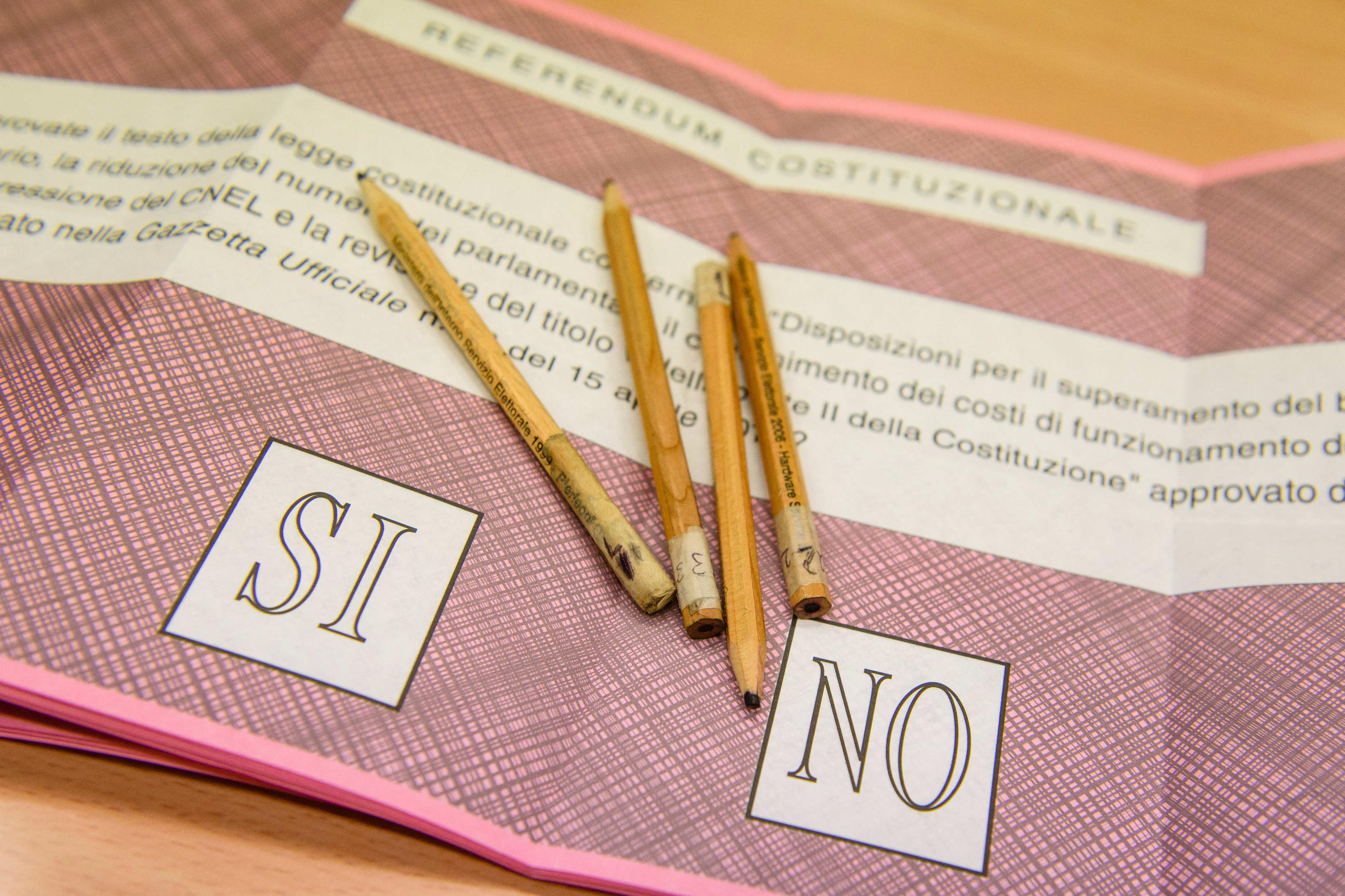

When local voters say: ‘Not in my own backyard’

Switzerland’s system of direct democracy is strongly anchored at the local level. Occasionally, a small number of citizens can bring down a project of wider importance, such as a second national park. But is this a problem or a safeguard?

Two examples from the past year may help illustrate the dilemma. In November, four mountain villages threw out a plan for a major park in the southeast of the country.

Five months earlier – and further north – voters in two cantons rejected a CHF10 million ($9.8 million) credit, disappointing supporters in a third canton, who had backed a project for a National Exhibition in eastern Switzerland, planned for 2027.

Political scientist Adrian Vatter of Bern University calls this gap between local and national interests the ‘not-in-my-own-backyard’ attitude.

He says this phenomenon occurs regularly in votes on public services, including infrastructure projects, such as motorways, railway lines or refuse incinerator plants.

Arguably, the most high-profile issue is the search for a site to store radioactive waste from the country’s five nuclear power stations.

The local population is more directly affected by traffic, noise or environmental risks than people in other parts of the country. Residents argue that they shoulder most of the burden while others only reap the benefits.

But it is not that simple. The local population might also be on the winning side. Take the case of a motorway by-pass built with money from the federal government to ease traffic on congested local roads.

No ‘democracy dilemma’

Sarah Bütikofer, a political scientist at Zurich University, dismisses the notion of a ‘democracy dilemma’.

“We know how the population in the cantons and municipalities directly concerned have voted, but we don’t know what the result of a nationwide vote would have been,” says Bütikofer, who is also editor of DeFacto, the Swiss platform for political sciences.

Andreas Gross, a political scientist with extensive experience as a member of the Swiss and European parliaments, refuses to use the term ‘democracy dilemma’.

“It shows the concern not to impose a major project without giving the population affected a say,” he says.

Democracy expert Gross says veto power is “a manifestation of a good and circumspect decision-making process”. The veto option often makes proponents pay special attention to drafting their proposal and considering the justified concerns of certain groups. The aim is to avoid outright opposition of the local population against a project.

Political scientist Sandro Lüscher of Zurich University believes it is perfectly legitimate to give more importance to the interests of the local population. “They are the first to feel the impact, good or bad, of such a project.”

It would go against the “democratic culture of deliberation as we know and live it” to impose a project against the will of the local population. “And this would deeply undermine trust in the local authorities,” says Lüscher.

No ‘winner-takes-it-all’

It may not be in the end of the world if there is no second national nature park in Switzerland or if there is no National Exhibition in 2027.

But what happens if opponents of a storage site for nuclear waste staunchly defend their above mentioned “own backyard”?

Political scientist Vatter says the different interests cannot always be fully reconciled, but he argues that conflicts can at least partially be pacified if the most important criteria of a regional and local participatory process are observed right to the end. These include “involvement of the local population at an early stage, transparency, fairness, sustainability and predictability”.

This is the third and final text in a series of swissinfo’s #DearDemocracy site looking back over the past 12 months.

The other contributions are Claude Longchamp’s The ten flops of democracy in 2016 and Democracy in 2016: all’s well that ends well by Bruno Kaufmann.

Vatter, who heads the research project on participatory disposal policyExternal link at Bern University, is offering his expertise to develop a prototype for a participatory process. The aim is to enshrine the criteria in the search for a storage site for nuclear waste, which has been locked in a stalemate for decades.

Consensus politics

Gross, for his part, says it is crucial that all sides involved in a process grant special benefits to those having to endure the negative impact of a project.

“This may be an incentive to shoulder a potential burden for the greater good,” he explains.

In line with Gross, Lüscher doesn’t see a possibility to overcome the different interests.

“I can’t be done without curtailing the sovereignty of the local population, which would be completely wrong and dangerous. Finding ways of settling conflicts of interests is the very essence of a consensus-oriented democratic system,” Lüscher says.

Finally, should the opinion of the local population or higher general interests count more in Switzerland’s political system?

Bütikofer pleads for a case-by-case approach: “But there are subordinate principles that are not negotiable.” They include human rights, the protection of natural resources and the respect for the constitution.

For Lüscher, however, the local population should come first. “As long as there is no subordinate interest that can be can justified as an emergency situation, as is the case with the disposal of nuclear waste,” he cautions.

Gross steers a middle course. Both the local concerns as well as the general interest count the same for him.

“But there may not be too much of a subordinate general interest if I fail to convince the local and particularly affected population,” Gross concludes.

Democracy power at a local level – boon or bane? Let us know what you think.

Adapted from German by Urs Geiser

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.