Switzerland – ‘a populist country in the best sense of the word’

Is “populism” something to be stamped out? German journalist Ralf Schuler, who recently wrote the book “Let us be populist”, says such movements are healthy expressions of dissent in democracies. Politicians should listen to populists, he says.

swissinfo.ch: Does “populism” exist?

Ralf Schuler: Populism certainly exists. But the word is used wrong. “Populism” is not a political category like liberalism, socialism, or conservatism, but rather an increasingly important political technique offering simple answers for complicated questions and leading people down the wrong path. Democracy is the rule of the mediocre; neither the idiots nor (unfortunately) the most intelligent can ever get a majority. And so the temptation is to offer simple recipes rather than complex – but sound – solutions to attract as many voters as possible.

swissinfo.ch: Is populism growing in Europe?

R.S.: Yes – movements under the general heading of populism are clearly growing. We see this in the Nordic nations (The Finns Party, the Sweden Democrats), in France (National Rally), in Britain (UKIP, the Brexit Party), and also in southern Europe, with left-wing groups like Podemos in Spain and Syriza in Greece.

We shouldn’t try to suppress this, however. Rather we should take note of the fact that “populists” are a type of warning signal for democracies: such movements take up issues that have been left untackled by established parties. Most often, in western societies, these issues are migration, national identity, or the integration of Islam. The rise of populism also signifies an important loss of trust in established parties, their politicians, and their policies.

swissinfo.ch: How do you reach your conclusion that populism is not a negative phenomenon?

R.S.: Wherever populism is strong, people speak out because they want politicians to solve certain problems. That’s a good sign: rather than sliding into apathy or not voting, people express their voice democratically. In most cases populism leads to higher voter turnouts, since its opponents are also spurred into action.

Problems arise when the other parties don’t accept populists as legitimate competitors in the market of opinions. They try to exclude populists and restrict their access to platforms. But such cordoning off doesn’t work in the digital age: populists simply move online into their own spaces, where they build their own truths – truths that then become more and more difficult to handle when they return to the “real” political stage. The outcome is polarization and irreconcilable differences.

Ralf Schuler, born in East Berlin in 1965, is head of the parliamentary section of the Bild newspaper in Germany. His book “Lass uns Populisten sein: Zehn Thesen für eine neue StreitkulturExternal link” (“Let us be populists: Ten theses for a new culture of debate”) is published by Herder press.

swissinfo.ch: What changes are you hoping for when you say, “Let us be populists”?

R.S.: Very simply, populism is a basic ingredient of any political system and belongs in the middle of society, not at the margins. Politics, as the art of leading the “polis” (the city, in Greek) must represent people’s concerns. Establishment politics must return to the people.

It often seems that voters are seen by politicians as a sort of nuisance. But this is how it should be. Politicians must expand their awareness, listen more, watch more, see which issues are stirring online. They need to recognize when migration is leading towards societal splits, when sales of blank guns and pepper spray are rising sharply, when fear is in the air.

Globalisation, international trade, the European Union: good politicians don’t abandon such issues to those shouting from the margins; they place them at the centre of debates, where they can be mapped out using clear democratic and humanitarian principles.

swissinfo.ch: If not with the “catchphrase” of populism, how should we best describe the similarities between politicians like Marine Le Pen, Matteo Salvini and Geert Wilders (among others)?

R.S.: Many of these so-called populists are in reality national-conservatives. As for Wilders, he focusses almost exclusively on one issue, Islam. But though such a term [national-conservative] is more politically precise, I can understand that “populism” is used in political debates. As a derogatory, exclusionary term, it’s very useful for the opponents of these movements.

Even the German Federal Centre for Political Education classifies it as a “stigma word”, used to disparage political opponents. The term is so vague and unspecific, and there’s an implicit danger that it’s used to mark out a sort of political exclusion zone, separate from serious politics. That will not work.

swissinfo.ch: How should the media use the word populism?

R.S.: Above all it should use it more sparingly, and when it does, it should use it for what it means: over-simplification, the peddling of easy solutions that probably won’t work, the stoking of false hopes, the determination to keep voters stranded in ignorance.

The danger for democracy lies in the fact that voters are often lured by such easy recipes, while their eventual failure just leads to more frustration and radicalisation. But though most populist movements can be analysed [by the media] without reaching for the “killer” term of populism, I can understand that this is difficult.

More

‘Revolution will never start in Switzerland’

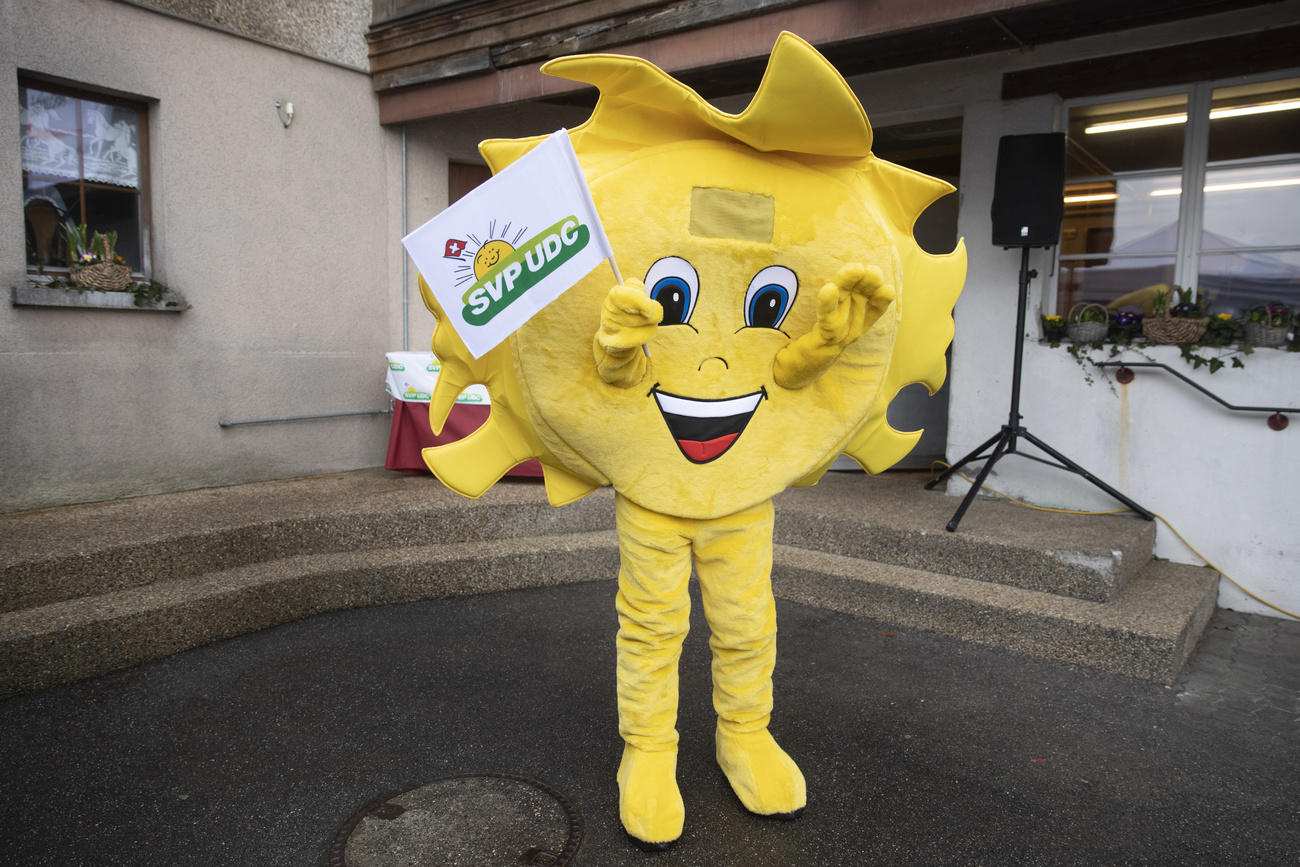

swissinfo.ch: Do you see Switzerland as a populist country?

R.S.: If I had to, I would call Switzerland a populist country in the best sense of the word. The tradition of allowing the people to vote on current and sensitive issues ensures a solid connection between politics and citizens.

I greatly admire the Swiss model, but I know it’s not easy to transplant such a tradition to other countries not versed in it.

swissinfo.ch: Are certain countries, cultures, or languages more susceptible to populist politics than others?

R.S.: No. I see no connection between populism, nations, languages, or cultures. What’s noteworthy, on the other hand, is that populist movements always spring up in places where clear issues are not solved; in most European countries this means migration, integration, Islam, and social cohesion.

Another factor is a big urban-rural divide. This is not only the case in the US, but also in Britain, Germany, and France. In these places, the metropolitan elite wrongly assumed that their worldview, and their lifestyle, was representative. But things like openness to globalization, sustainable living, migration, and gender diversity are viewed very differently in cities and in the countryside.

And it’s easy to forget that in a democracy, majorities decide, not morals or attitudes.

This is the third and final part of a series on populism in Switzerland. On Tuesday we published an overview of the situation, and on Wednesday featured a profile of Young Socialist leader Tamara Funiciello. And here’s an attempt to define what populism actually means.

swissinfo.ch: Do you see a direct connection between populist rhetoric/policies and direct democracy?

R.S.: Direct democracy presents an additional challenge for politicians to make their policies comprehensible, to the point, even exaggerated or attractive. But direct democracy is not necessarily directly linked to aggressive rhetoric, attacks, or “baiting”.

Again, I see that rhetoric becomes more radical in those places where establishment politics has persistently refused to deal with contentious issues. Populist movements attract people from the margins who are susceptible to their arguments.

swissinfo.ch: You mention digitalization as having expanded public debate and voices, which has contributed to the current fracturing of European politics.

R.S.: Yes. Twenty years ago, the mass media had a monopoly over information, whereas today the masses have taken media directly into their own hands. Today, when it comes to societal debates, it’s no longer a question of if they will be discussed, rather where they will be discussed.

When radio, television, and newspapers don’t take up such issues, they move online, where they develop their own dynamic, which then sometimes returns – more powerfully – to society.

The best example was the debate around the UN Migration Pact, which in summer 2018 was already boiling over online, as neither the traditional media nor parliaments were discussing it. The outcome was a distrust of this type of international agreement and several states pulling out.

swissinfo.ch: What changes can we expect in the future?

R.S.: If we want to prevent more polarization and radicalization in society, politics must become faster, more direct, and more credible in dealing with the pressing issues. For example, politicians must set effective limits on migration to and within Europe, so that the acceptance levels of host populations are not strained, and the integration of migrants contributes to the organic growth of society.

Protests against the TTIP trade agreement between the United States and the EU showed that global free trade, and the mutual benefits it brings, needs to be seriously clarified. Perhaps European and international cooperation also needs to be re-defined: less fixated on unanimity and more open to national divergences and identities.

Europe should focus on regulating the important things, those which are beyond the capacity of nation-states – not the daily lives of people. The G7 or G20 should see dialogue and exchange as an end in itself, instead of producing empty conclusion documents. Political rhetoric needs to become simple and understandable, political actors credible and with an ear always open to the people.

More

In Switzerland, populism thrives – but under control

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.