Four decades on, Switzerland’s newest region is still growing up

Born in 1979, Switzerland’s youngest canton still owes much of its political and economic fate to the federal system that houses it.

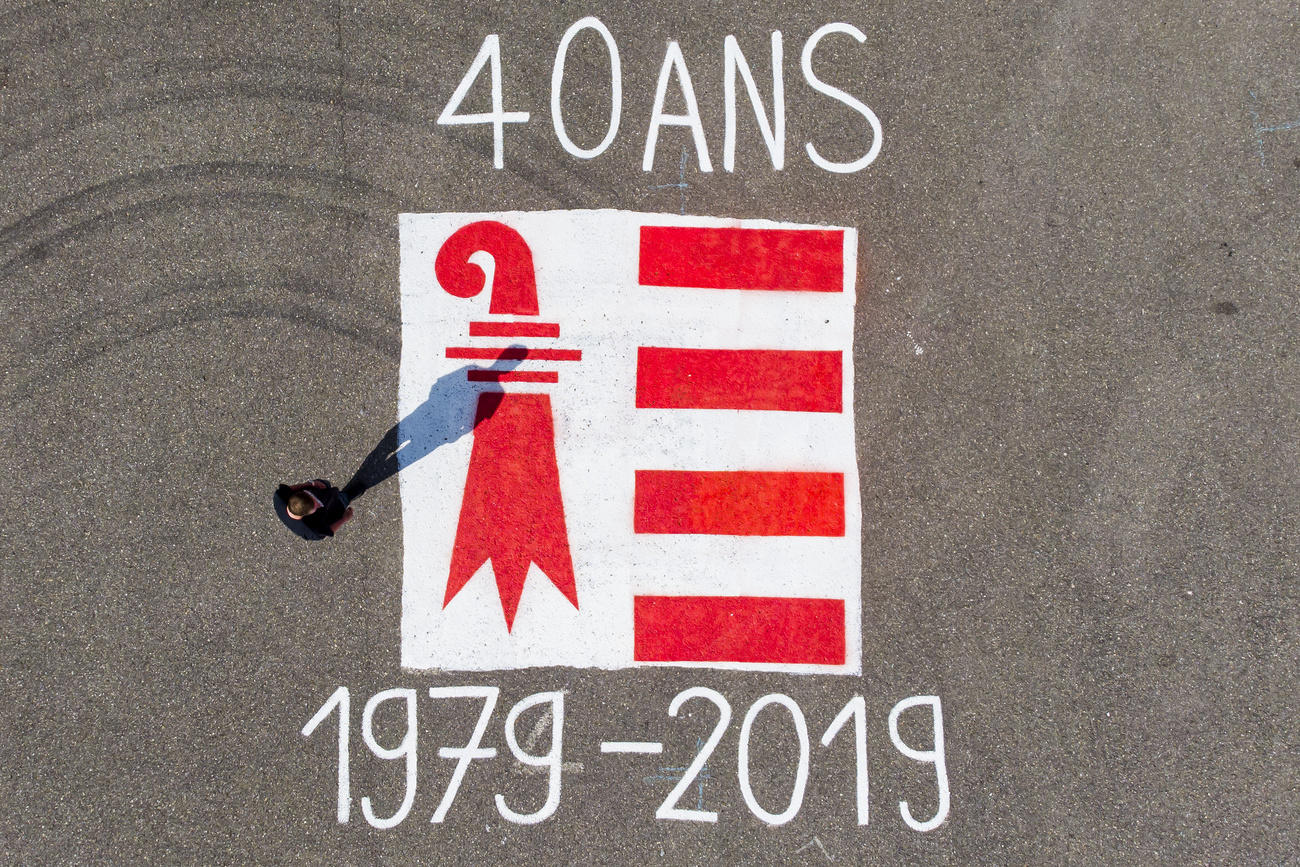

Four decades ago in Delémont, the small capital of the north-western Swiss canton of Jura, thousands gathered on the Place de la Liberté to celebrate the birth of a nation.

“Citizens,” proclaimed François Lachat, the canton’s founding father – “victory!”

After decades of strife, negotiation, and referendum, Jura had been accepted as an entity by its 25 new siblings, the other Swiss cantons, and on January 1, 1979, it seceded from Bern to become Switzerland’s youngest federal region.

Forty years later on the square, the same, huge, 200-year-old linden tree still surges up from under the sloping cobbles; the even older Bernese-style fountain, an ironic reference to the former occupying force, still sits in front of the steps leading to the town hall; only a photo-friendly family of Chinese tourists, presumably a rarity in the 1970s, suggests time has passed.

But time has passed: in the case of Jura, enough time to build a working canton and administration, along with everything such a job entails – viable budgets, a tax system, civil servants, number plates, permits, roads, foreign relations.

How does a new Swiss region go about such a thing?

Nation-building 101

With difficulty, and not overnight, says Fabien DunandExternal link, a former journalist who was in Delémont for the 1979 celebrations and who wrote a biography of Lachat in 2015.

Once the political goals had been secured, Dunand tells swissinfo.ch, the three things that were vitally necessary for bringing the new canton to life were: civil servants, the infrastructure to allow them to work, and – above all – money.

The first need was solved by massive civic enthusiasm: over 4,000 applications (in a canton of just 70,000) were received to fill 450 civil service positions. The second was solved, at least initially, through improvisation: Jura’s new administration set to work in apartment buildings, using wooden crates as desks and working hard hours.

Cash was trickier. This involved returning, cap in hand, to Bern, for a dig-out that almost didn’t materialise: a CHF40 million ($40.77 million) “starter loan” was initially rejected by the federal chancellery, and it was only Lachat’s off-the-cuff threat that the canton would not become independent after all on January 1, 1979 that led to the funds being released, interest-free. This enabled Jura to then approach Switzerland’s biggest banks for a further CHF80 million to invest in hospitals, schools, justice, and policing.

What would have happened if the money hadn’t been found? It’s difficult to say. But even with it, Dunand writes that Lachat – who was finance minister as well as president of the first Jura government – would close the account books each Friday evening with a looming dread of bankruptcy, which led him to take some drastic measures in the first six months.

“I decreed that elbow grease should partially replace heating oil,” Lachat (partially) joked. “I asked that room temperatures not be higher than 18°C. Two days later the secretaries were working in scarves and mittens. We quickly shelved that idea.”

Not quite paradise on earth

As anyone who has worked in the rather uncommon job of building a state will presumably attest, elbow grease is more than just a euphemism: civil servants, and especially government ministers (and especially Lachat), worked themselves to the point of exhaustion to get the new administration on its feet.

“After a few months of work, I was dead,” said Lachat. “Nobody was counting the hours.”

Or, as his colleague Jean-Paul Beuret, Jura’s first economics minister, put it: “building a state is not quite a ticket to earthly paradise”.

Vehicle registration plates needed to be organised and printed (one of the most important early tasks, Dunand says: proud citizens were hugely enthusiastic about having the symbolic “JU” on their cars); taxes needed to be set, then collected (Jura had one of the heaviest tax regimes in Switzerland at the time, to generate much-needed income); investors needed to be seduced and imported (Jura was quite geographically isolated and under-developed).

And all this is without mentioning the thorny question of resources already present in a canton previously ruled by neighbouring Bern. Who owns that hospital, built by Bern but now standing in autonomous Jura? Who owns that prison, who should pay to supervise those prisoners? Questions that were only resolved after six years of acrimonious negotiations.

Tracking progress

Four decades later, have the “providential” (Dunand’s description of Lachat) efforts of the pioneering Jura politicians work?

When we meet current finance minister Charles Juillard, he’s wearing a short-sleeved shirt in his office, where he also has two desks to work with. (The ministry itself, on the outskirts of Delémont, still looks suspiciously like an apartment block).

Juillard was 16 when the canton was born. Now 56, he’s been finance minister for the past 13 years, two shy of the constitutional limit for such a job, and is planning to finish up and run for a national Senate seat in this month’s elections.

He sees clear progress forty years on – so much so, that “a sort of normalisation” has crept in, he says. Jura has become used to autonomy, to finding solutions for its own problems, and to working within the federal system.

“Catch-up investments” over the past decades enabled the canton to progress from being a “forgotten” corner of Bern to becoming an entity that takes its destiny in its own hands, he says: big projects like the all-important motorway running through the region to neighbouring France might never have been built if it wasn’t for Jura’s ability to go and argue its case to the national authorities in Bern.

And according to historian Christoph Koller, writing recently in Le Temps, Jura is by no means suffering from a mid-life economic crisis: despite difficulties over the years, its manufacturing sector (mainly watches and machine parts) has remained strong, still employing over 40% of its workers, while its tertiary sector has ballooned – from 32% to 56% of jobs between 1975 and 2016. Unemployment is low, at 4.6%, and thousands of cross-border workers enter the region each day from neighbouring France and Germany.

(By comparison, 21.5% of workers in Switzerland are in the secondary, or manufacturing sector, while 78% work in tertiary services; the national jobless rate stands at about 2%.)

Juillard also mentions the canton’s comparatively low debt rate, claiming finally that “Jura is now a canton almost like any other” – the cautious almost referring to the political, rather than economic, situation in the town of Moutier, which voted in 2017 to leave Bern and join Jura, but where the tense situation remains unresolved (see below).

More

Thousands of separatists protest Moutier vote court decision

Federal struggles

But the canton is definitely not yet out of the woods. Though Juillard is adamant that “the economy is going well”, his region remains the national laggard.

Each year, Switzerland’s “fiscal equalisation” system organizes a giant pot into which rich (or “resource-potential” rich, as the lingo has it) cantons pour in cash that the poorer cantons then receive in order to tide over their balance books and infrastructure. As we reported recently, powerhouses like Zug and Zurich end up contributing most, while at the bottom of the pile, Jura invariably ends up being the biggest receiver.

“It [the fiscal equalisation system] is very important for us,” says Juillard. Each year, for a total of around CHF930 million of cantonal expenditure, some CHF160 million of this comes from the communal federal pot – a sizeable dependency.

However, he notes that while the federal system helps Jura cope with its expenditure and its tricky geographic location, it also creates extra work and costs.

Bern makes decisions at the national level that must be implemented at the regional, Juillard says, but it doesn’t always adequately give what’s needed by the cantons to cover them. He mentions asylum regulations and unemployment as examples of costly federal policies partly paid for by the cantons.

He also regrets the recent revision to the fiscal equalisation system, which will see (from 2020) richer cantons contributing slightly less, and poorer cantons losing out. “This is not good for the weaker cantons,” Juillard says. “We have a good redistribution system overall, but we need to make sure it remains good.”

He criticises the federal authorities – currently sitting on big economic surpluses – for not stepping up to meet the shortfalls, proving once again that in the game of Swiss politics there will always be a certain animosity between Bern and the cantons, who fiercely guard their independence while at the same time relying on the centre for all manner of coordination and help.

Indeed, as Dunand puts it, when it comes to the history and current fortunes of Jura (as with the other cantons), federalism could be seen to have both helped and hindered it.

More

How wealthy Swiss regions subsidise their poorer cousins

domhnall.osullivan@swissinfo.ch

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.