Eiger claims two more victims

Rescue workers have retrieved the body of one of two mountain climbers who froze to death on the Eiger this week after being trapped by a storm.

It was the first tragedy this year on the 3,970 metre high Eiger – a mountain regarded as one of Switzerland’s most dangerous and whose name, some people think, means “ogre”.

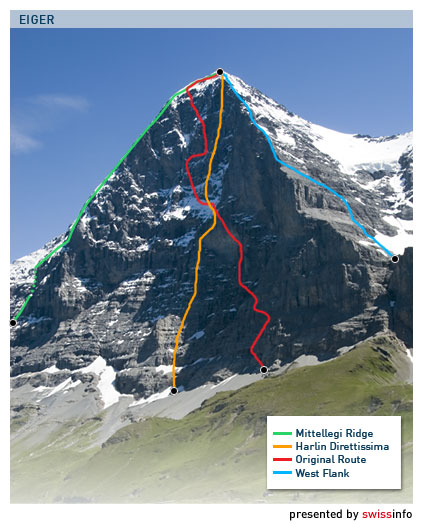

Poor weather thwarted the recovery of the body of the other man, who had attempted with his friend to scale the peak’s notorious north face, one of the most challenging in the Alps.

The two mountaineers, who have not been named, were found frozen to death, not on the treacherous north face, but on a ridgeline leading back towards a mountain hut and the Jungfraujoch railway station, a popular tourist attraction.

Both climbers were recruits on vacation from the Swiss army’s mountain training centre based in Andermatt. By all accounts they were experienced and well prepared. They had almost certainly reached the summit before becoming trapped.

“But did something happen to them already on the way up the north face?” wondered Christian Brawand, president of canton Bern’s mountain rescue service that was involved in the effort.

“I don’t think the Eiger is much more dangerous than other mountains, but like all over the Alps, the situation can change very quickly,” he told swissinfo. “These two young climbers made the proper planning. We just don’t know what happened. We may never get answers.”

Fighting to survive

What is known is that the two men, aged 22 and 21, had set out Sunday morning. The weather had been clear that morning with cold temperatures and wind.

Ueli Steck, a Swiss mountaineer who holds the speed record for climbing the north face and knows the mountain well, said the conditions that day were good enough that he, too, would have started the climb. But weather reports did show a storm was moving in.

The two climbers were tackling the face’s original route, the 1,800-metre Heckmair Route, a steep and exposed line climbed by the German-Austrian team which made the first successful ascent in 1938. People in the village below said they saw lights that evening near the spot known as the Flatiron – probably the climbers making camp.

Relatives began to worry when the men did not call to check in that night. The next day they reported them missing. Word reached a mountain rescue station in Grindelwald late on Monday night, but by this time the weather had deteriorated, making a helicopter rescue impossible.

“We just couldn’t reach them,” Marc Ziegler, head of the Grindelwald rescue station, told swissinfo. “That is unusual but the conditions made it not possible.”

The men probably did the best thing they could have in such a situation and hunkered down in a snow cave or behind rocks out of the wind. They survived the night.

Contact lost

Early on Tuesday morning, the father of one of the climbers briefly reached his son on his mobile.

“He said they had cold fingers and feet but they sounded optimistic,” Ziegler said. Rescuers had time to learn where the climbers were before the signal went dead.

The rescue could then begin in earnest. But the temperature had dropped to –22 degrees with wind gusts up to 80km/h. As much as a metre of new snow choked the way to the stranded climbers.

“To go just ten metres people needed a half an hour,” Ziegler said.

The effort was called off later that afternoon in worsening weather. By early Wednesday morning four helicopters, including one from the Swiss army with infrared imaging capabilities, were able to fly toward the ridge and spotted the men. A doctor and a police officer dangled beneath one helicopter from a cable and were able to get within five metres of them.

From what they could see, it was clear the climbers had frozen to death.

Death toll rises

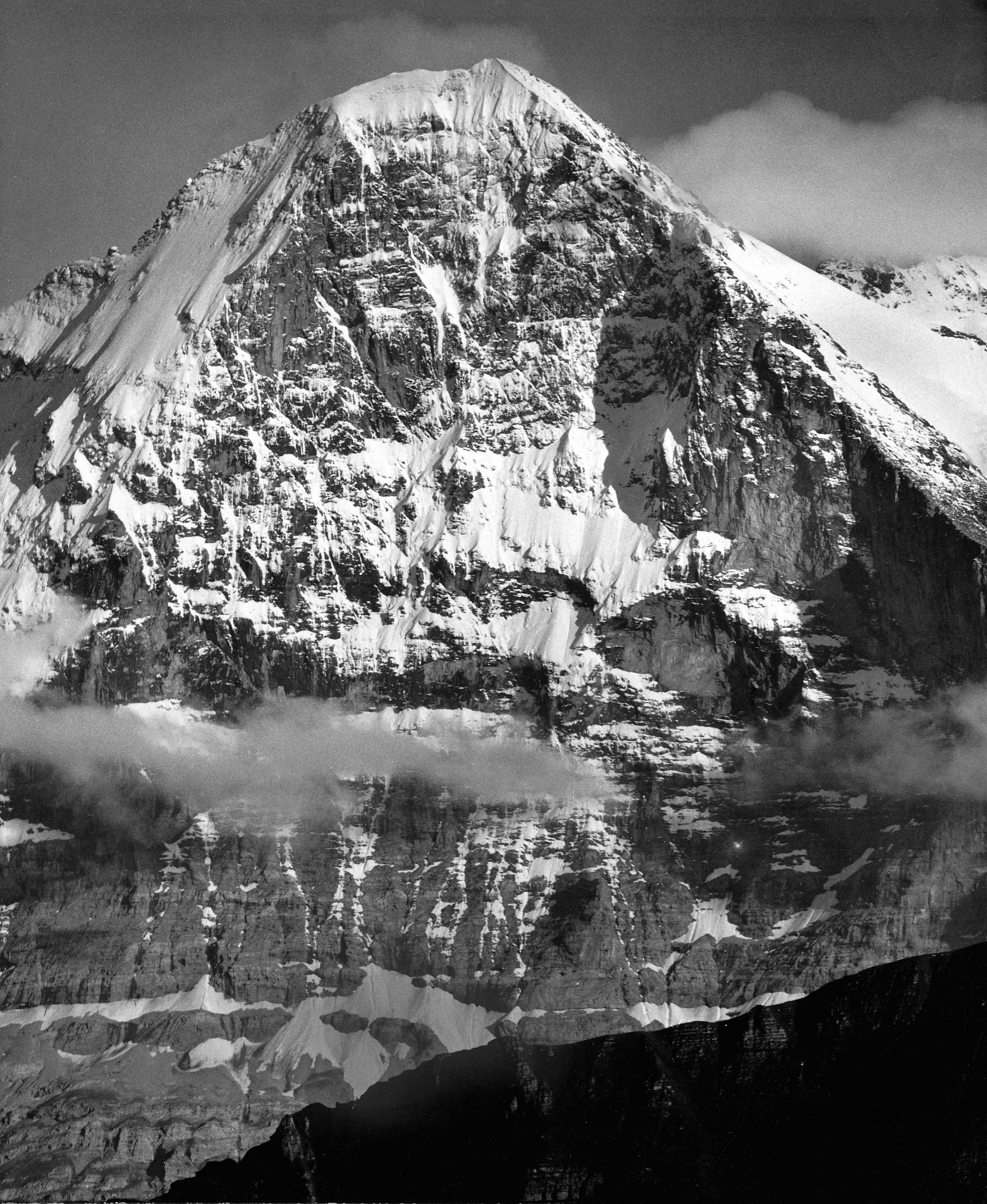

The Eiger has been the scene of a number of horrific dramas, which have struck the public imagination because the north face sits within easy view of villages below, allowing people to watch tragedies unfold.

To date more than 60 people have died on the mountain, which can be dangerous because of loose rock and storms that gather in an instant.

Climbers have died within feet of windows cut through the rock during the building of the railway that runs through the mountain. Some corpses have been left to dangle for weeks as the terrain is often too difficult for rescuers to retrieve bodies quickly. The death of two British climbers who fell in 2000 was caught on film.

“The dangerous part about the Eiger isn’t the north face,” Steck told swissinfo. “There you are moving slowly, securely. It’s when you get to the parts where you can walk more quickly that you will make a mistake.”

Janine Patitucci, a professional mountain sports photographer from Lucerne, used nearly the same decent as the ill-fated climbers after her climb up the peak a few years ago. She said the route the climbers may have been trying to go down can be worse than the way up.

“It’s just so exposed,” she said. “In a storm it would have been terrifying.”

Rescuers were hoping the weather would improve on Friday to allow them to retrieve the other body but high winds thwarted those efforts.

In the meantime, friends, family and colleagues are grappling with what went wrong.

“He had always talked about the mountains as ‘his’ mountains,” the father of one of the men said. “Now the mountains have kept him.”

swissinfo, Tim Neville

After Pakistan’s K2, few other peaks are shrouded in such a macabre mythos as the north face of the Eiger.

The mountain, which from some angles looks like a mini Mount Everest, was first climbed in August 1858 by a Swiss guide and an Irish client who used the far easier west flank to reach the top.

As 20th century mountaineers began to set their sights on more challenging routes up peaks, Germans were the first to focus their efforts on the Eiger’s far more daunting north face.

It is an 1,800-metre-high wall, with vertical sections of rock and ice that rain debris down on climbers.

The first people to die on the face were Max Sedlmayer and Karl Mehringer who perished in 1935.

In 1936 a climbing party of four was wiped out after an avalanche knocked them off the wall. One climber fell to his death; another was killed when he smashed into the rock face. A third, roped to the other two, died after the rope pulled him tight against the wall and asphyxiated him.

The fourth climber, Toni Kurz, was uninjured but left dangling on the mountain for two days.

Rescuers could get within feet of him but his fingers were so badly frozen he was unable to manipulate his gear to lower himself a few feet to reach help. “I can’t go on,” he said and died.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.