Experts mull foreign impact of minaret ban

Six months on, tensions over the ban on new minarets seem to have eased, but the issue has not gone away and the country’s image abroad has been tainted, say experts.

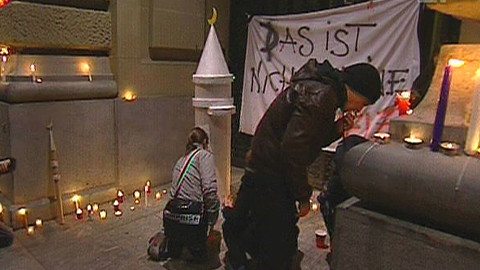

Swiss voters’ decision to ban the construction of minarets on November 29, 2009 sparked worldwide criticism from Muslim groups, governments, the United Nations and the Council of Europe – and praise from the European right wing.

After the initial wave of international condemnation, the Swiss vote has continued to come in for official criticism – albeit sporadic.

In March the US State Department annual report on human rights cited it as an example of anti-Muslim discrimination in Europe.

Later that month the Geneva-based UN Human Rights Council backed a resolution, proposed by the Organisation of Islamic Conference (OIC), calling the ban a “manifestation of Islamophobia”.

But there are signs that tensions have slackened off. Erwin Tanner, a top official with the Swiss Bishops Conference who recently travelled to Syria and Lebanon for inter-religious talks, felt the issue was “part of the past”.

And the European Court of Human Rights, which is considering six appeals against the ban, said it had received only two letters of complaint in April, compared with 50 per day at the end of January.

Six months on, initial fears about a violent backlash or an economic boycott by Muslims, similar to that experienced by Denmark after the Mohammed cartoons affair in 2006, have not been realised.

“The reactions to the ban by Muslim countries and Islamic organisations were very critical in tone, but mostly moderate, and with only a few exceptions, there were no calls for boycotts by government officials or politicians,” Swiss foreign ministry spokesman Adrian Sollberger told swissinfo.ch, adding that Switzerland’s global image remains “good and stable”.

He pointed to a recent poll by St Gallen University, “Swissness Worldwide 2010”, that suggests that the minaret ban has had little impact on Swiss products and services.

The State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (Seco) confirmed the limited economic impact.

“We have no hints of any problems involving Swiss companies in Muslim countries as a result of this vote,” said Seco spokesperson Rita Baldegger.

Damage-limitation

Sollberger claimed the largely moderate reactions were thanks to an “active” information campaign by Swiss diplomats to their counterparts, religious leaders and civil society groups in Muslim countries before the vote.

This was followed by intensive contacts between the Swiss government and OIC member states and European foreign ministers, which continue.

Former Swiss ambassador François Nordmann felt this damage-limitation exercise seemed to have successfully reduced tensions.

The nomination of former Swiss cabinet minister Joseph Deiss as candidate for the office of president of the 65th UN General Assembly, and Switzerland’s re-election to the UN Human Rights Council, were key indicators of the absence of diplomatic hostility towards Switzerland, he said.

“But it’s obvious that the international image of Switzerland, which presented itself as a human rights role model, has been dented,” he told swissinfo.ch.

“It’s forced us to become more modest.”

Hasni Abidi, director of the Study and Research Center for the Arab and Mediterranean World, agreed tensions had abated but felt this was more due to time than Swiss diplomatic efforts.

More worrying, he said, was that the average person in the Arab world did not comprehend the vote.

“I’ve just come back from a tour of the Gulf states and every time we talk about Switzerland people say they don’t understand why the Swiss voted in that way,” he said. “Switzerland’s image has taken a real battering.”

Pioneer

Yves Lador, a Geneva-based human rights specialist, felt the international impact of the “pernicious” vote was mixed six months on, but it was likely to have negative consequences in the long run.

“It’s like an infection that is there and hurts but still enables us to function,” he said. “But it could suddenly develop into something big and weaken us.”

While Switzerland continues to enjoy European support, certain countries will not hesitate to bring out the minaret “trump card” during future bilateral discussions, said Lador.

Both experts were concerned about the foreign perception of the Swiss vote and the way it was influencing the debate about Islam in other European countries.

“When you read in the Arab press about anti-burka campaigns in Belgium or France they all talk about Switzerland as the pioneer that dared try something before the others,” said Abidi.

Belgium’s lower house of parliament voted in April for a law that would ban women from wearing the full Islamic face veil in public; the law now goes to the Senate. In France a similar bill is due to go before parliament in July.

In the German region of North Rhine-Westphalia two rightwing groups this month called for a ban on minarets, heavily inspired by the Swiss People’s Party’s campaign and posters.

The northern Swiss canton of Aargau passed an anti-burka proposal earlier this month and on Tuesday the Geneva-branch of the Swiss People’s Party launched a new proposal calling for a cantonal ban on burkas. A constitutional committee will examine the question next year and if it passes, local residents could vote on the issue in autumn 2012.

“We are contaminating each other,” said Lador. “A ban on burkas in Geneva would destroy tourism from the Middle East. If that happens the impact would be worse than for minarets.”

Simon Bradley, swissinfo.ch

This article is the first in a series of three examining the situation six months after the nationwide vote on November 29, 2009 banning the construction of new minarets in Switzerland.

The Muslim community in Switzerland accounts for about 4.5% of the population.

Most Muslim immigrants came from the former Yugoslavia and Turkey. The community includes up to 100 nationalities.

The number of Muslims doubled between the censuses of 1990 and 2000, largely boosted by an influx of refugees and asylum seekers, including from the war in the former Yugoslavia.

There are about 200 mosques and prayer houses in Switzerland, but only four have a minaret.

On November 29, 57 per cent of voters supported a people’s initiative to ban the construction of new minarets in Switzerland. This was in the wake of heated debates and legal battles at a local level about requests by mosques to build more minarets.

In recent years, both mosque and minaret construction projects in many European countries, including Sweden, France, Italy, Austria, Greece, Germany and Slovenia have generated protests, some of them violent.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.