Fair trade firm accused of foul play

A French economist has attacked the working practices of the Max Havelaar Foundation, which promotes fair trade between developed and developing countries.

Criticism is also aimed at the global organisation’s branch in Switzerland, where consumers are big buyers of Max Havelaar products.

The charges against Max Havelaar are detailed in a 500-page book, “Les coulisses du commerce equitable” (Behind the scenes of fair trade), by Christian Jacquiau.

Paola Ghillani, a former director of Max Havelaar Switzerland, disagrees with much of the content but says certain arguments carry some weight.

According to Ghillani, products certified as fair trade do not always live up to the tag due to a lack of proper controls among smaller producers.

A central question is whether a milk chocolate bar, made from fair trade cocoa beans, is really a fair trade product. The bar will also contain other ingredients, such as sugar, milk, almonds or nuts, which are not necessarily the product of equitable trading.

Cash crop

Fair trade consists of guaranteeing farmers in developing countries equitable prices for products such as coffee, chocolate and rice. It also seeks to ensure that they are produced in an environmentally sustainable way.

Consumers in the developed world then pay more for their fair trade coffee or orange juice in the knowledge that they are helping disadvantaged farmers. The added cost means that producers in developing countries can send their children to school, for example.

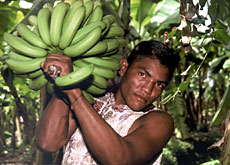

With an annual SFr30 ($24) per capita spent on fair-trade products, the Swiss are the champions of fair trade. More than half the bananas sold in Switzerland are stamped “Max Havelaar”.

But what concerns Jacquiau is how much of that money ends up in the pockets of farmers in developing countries.

According to figures issued by Max Havelaar, €50 million (SFr79 million) has been distributed among small farmers. At the same time, the organisation says it works with a million producers.

“Here the dream falls apart,” said the author. “They therefore each receive just €50 a year – or €4 a month.”

Fair return

But what’s even worse, says Jacquiau, is that it’s not even clear if the farmers are actually getting the money.

“There are only 54 inspectors around the world, working on a part-time freelance basis to check and control a million producers. These checks do not take place on the ground but in offices, hotel rooms or even by fax,” he says.

“The main beneficiary of the trade could well be a large landowner or even a multinational.”

Max Havelaar Switzerland firmly denies the charge and says the foundation strictly plays by the rules.

“In any system, there can be profiteers. But I can assure you that Max Havelaar not only carries out checks, but also controls these checks. We adhere to the international standard ISO 65,” says Regula Weber, spokeswoman for Max Havelaar Switzerland.

Didier Deriaz, spokesman for Max Havelaar in French-speaking Switzerland, is also adamant that the system works.

“This is not a panacea, this is the best way forward. More and more western consumers are convinced by fair trade. In developing countries, more and more producers and workers are reaping the benefits,” he said.

Coffee and burgers

In his book, Jacquiau also criticises the “partnership” between a champion of fair trade coffee and the 140 McDonald’s outlets in Switzerland.

Ghillani, who was director of Max Havelaar Switzerland until 2005, is unhappy with the general tone of the book, which “puts everyone in the same basket”. But she says Max Havelaar is seriously weak when it comes to checks.

Ghillani spent four years as president of the Fair Trade Labelling Organizations (FLO), which draws up international fair trade standards, monitors certification and controls.

“I always said that checks should not be carried out by the FLO but by outside organisations. We need professional, neutral and independent inspectors,” she said.

“It is a process I was beginning to put in place in Switzerland. But everything came to a halt after I left,” she added.

swissinfo, Ian Hamel

The fair-trade business is worth SFr1.7 billion a year. In 2005, Max Havelaar Switzerland reported a turnover of SFr221 million – up 5% on the previous year.

The Swiss spend an annual SFr30 per head on fair-trade goods, well ahead of the citizens of Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Britain, Denmark and Austria.

Max Havelaar bananas account for 56% of all fair trade products bought in Switzerland. Others include flowers, honey, fruit juice and coffee.

A kilo of fair trade bananas costs SFr2.60-SFr4.50. A fair trade pineapple costs SFr1.40-SFr1.60 – up to 33% more expensive than a regular pineapple.

1860: The novel “Max Havelaar, or the Coffee Auctions of the Dutch Trading Company” is written by Multatuli (Eduard Douwes Dekker).

1988: Max Havelaar Foundation established in the Netherlands.

1992: Swiss branch of the Max Havelaar Foundation set up by six non-governmental organisations.

1999: Paola Ghillani takes over at Max Havelaar Switzerland. Sales climb 600% in six years.

2005: Ghillani leaves and is replaced by Martin Rhoner, 39, a former executive director of the World Bank.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.