Getting your Neckers in a twist

Louis Necker, the Swiss mineralogist and crystallographer who gave his name to the Necker Cube optical illusion, died 150 years ago on November 20.

swissinfo.ch looks at the life and work of a man who was born into a family of Geneva geniuses and died a childless recluse on a Scottish island, making a key contribution to the study of perception along the way.

Louis Albert Necker de Saussure was the eldest of four children born into an academically and socially distinguished family (see box) – famous enough to get a page in Francis Galton’s Hereditary Genius (1869), the first social scientific attempt to study genius.

But despite all doors being open to him in Geneva, he decided aged 20 to travel to Scotland and study chemistry at Edinburgh University.

“He must have been well-favoured because he came quite young to Edinburgh and clearly had introductions to the great and the good there,” said Nicholas Wade, author of “Necker in Scotch Perspective”, a 2010 essay in the journal Perception (see link).

As to why Necker chose Scotland – where he would end up spending almost half his life – Wade, a professor of psychology at Dundee University, pointed to Edinburgh’s reputation as a university city.

As Necker wrote in 1821, “Edinburgh is not unworthy of the titles Athens of the North and the Capital of Mind, which many modern authors have bestowed upon it”.

Religion

Although Necker certainly didn’t have to worry about austerity measures, he lived frugally, later renting a room in Portree on the Isle of Skye with the Camerons, a Free Church family.

“The underlying characteristic is his Calvinism, which seems to run through his desire both to go [to Scotland] and then return there after he retired,” Wade told swissinfo.ch.

Then there were the legends of Ossian, a cycle of poems which the Scottish poet James Macpherson claimed to have translated from ancient Gaelic sources in the 1760s.

These turned out to be the Harry Potter of the day, selling like mad across Europe. A young Necker was known to be fascinated by Ossian and the “mystical land in the north”, as Wade put it.

Reclusive

But apart from Necker’s love of Scotland, very little is known about his personality. He never married and appears to have become more reclusive the longer he stayed in Portree, where he is buried.

“Certainly the notion of happiness was frowned upon by most of those on Skye – the Wee Frees [the Free Church of Scotland] in particular,” Wade said.

Nevertheless, Necker was very much a roll-up-your-sleeves scientist and a strong advocate of field observation.

His fieldwork included studies of the volcanoes of Italy, the geological features of parts of Savoy, Carniola, Carinthia, Istria, and Illyria, and the dike swarms on the Scottish Isle of Arran.

In 1832, he ensured his place in textbooks and dictionaries when he published the catchily titled “Observations on some remarkable optical phaenomena seen in Switzerland: and on an optical phaenomenon which occurs on viewing a figure of a crystal or geometrical solid”.

He had been doing research in the Alps and, looking at a drawing of a crystal, noticed that it appeared to assume different orientations – depth reversals – as he continued looking at it.

Reversal

Necker wasn’t the first to observe depth reversals in solid objects – Ptolemy was writing about the deceptive appearance of concave and convex surfaces in the second century.

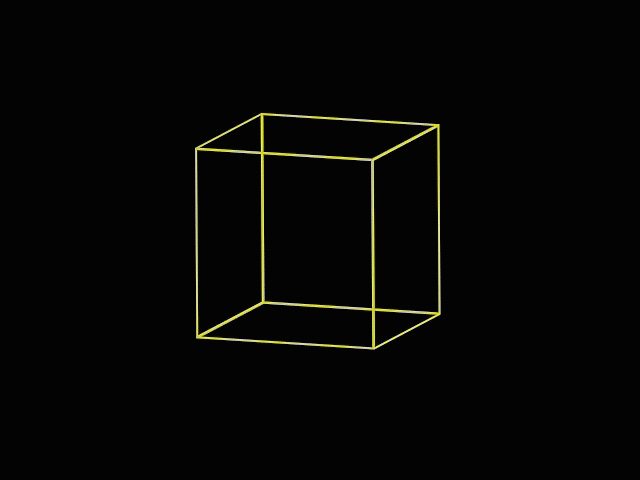

His cube is, however, the “earliest scientifically described ambiguous figure”, according to Wolfgang Einhäuser-Treyer, who in 2004 published a paper on the Necker Cube and perception (see link) while at the ETH Zurich.

Enlarge the main image above and stare at it. After a few seconds you will see a cube that looks three-dimensional. It will appear as though you are either above or below it. Keep staring and at some point the depth will “oscillate” and your viewpoint will change.

“The interesting thing for scientists is that you have a constant stimulus, yet seemingly spontaneously your interpretation of that stimulus switches. Which means this is all happening in your brain, because there’s no change in the world,” he told swissinfo.ch.

Research

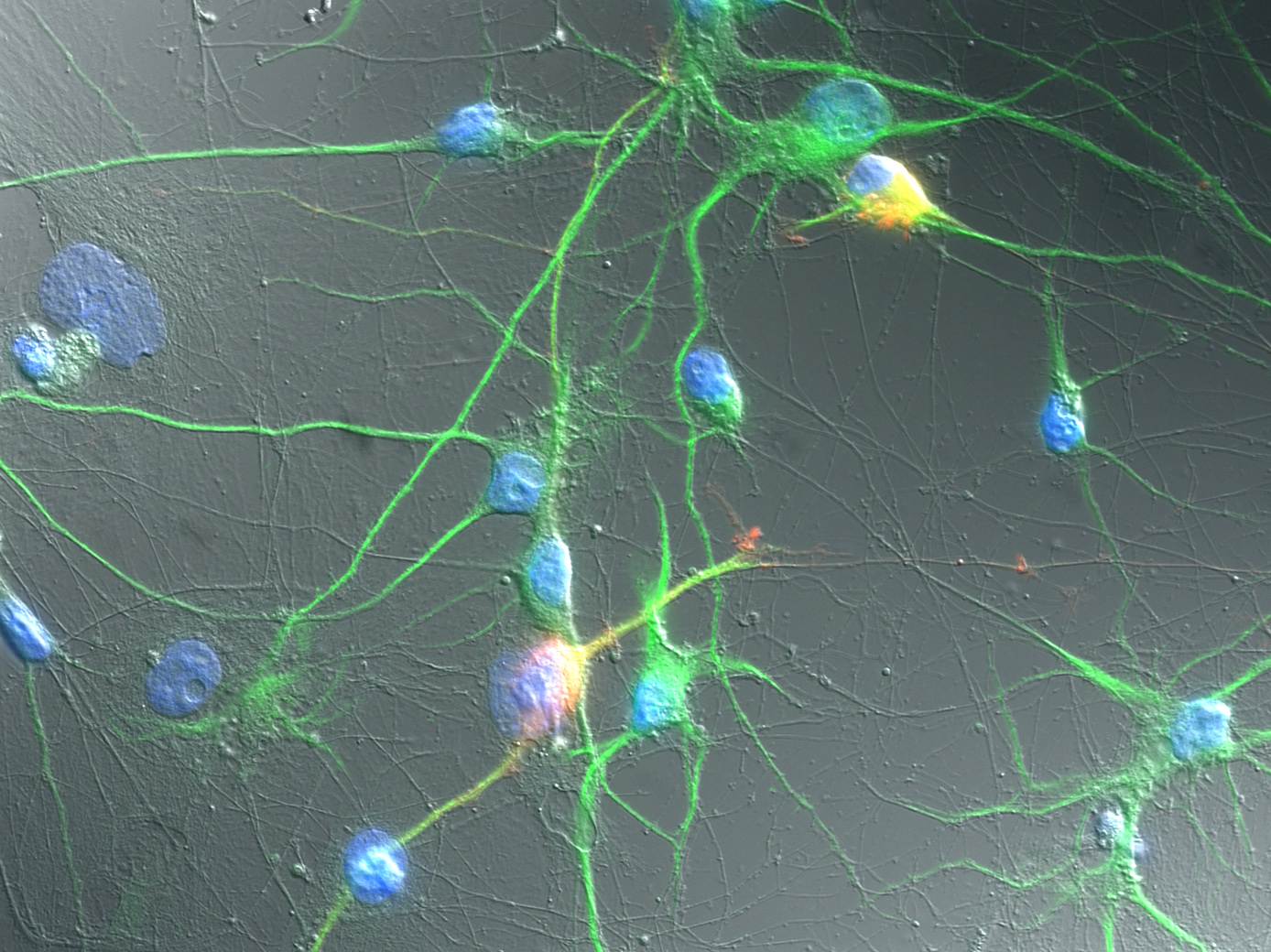

Einhäuser-Treyer, a professor of neuroscience now at Marburg University in Germany, said there were currently three major lines of research involving the cube.

“Your brain has to decide between one interpretation and the other, so we’re linking that to mechanisms of cognitive decision-making. So deciding whether to take the left path or right path is pretty much in the part of the brain linked to perception of figures like the Necker Cube,” he told swissinfo.ch.

“A second area is giving people drugs and seeing how their perception changes. This has dramatic effects. Even meditation: meditating monks have completely different rates in switching back and forth depending on their meditative state, which again tells you it’s all in the mind,” he said.

“The third idea is that your motor action – in this case an eye movement – influences your perception.”

Response

Sidney Bradford went blind aged three months but regained sight in both eyes after a cornea transplant at 52. Before killing himself two years later in 1960 – overwhelmed by a new world of colour and motion – he was the subject of many scientific studies, one of which discovered he could not perceive the ambiguity of the Necker Cube.

But all “normal” observers, including those with one eye, see spontaneous switching, according to Einhäuser-Treyer.

“There’s a debate whether you can voluntarily control it – and you can to some extent – but unless you’re a Buddhist monk, you can’t hold it for ever,” he said, adding that what is idiosyncratic is how long it takes people to switch.

“There are even claims – and this is still debated – that bipolar people who are in a manic state switch faster than those in a depressive state.”

Einhäuser-Treyer says he sees a third flat perception once in a while – “but that’s very specific to someone who’s been exposed to the stimulus for longer than one probably should be!”

April 10, 1786: Louis Necker is born in Geneva.

1806: Studies chemistry at Edinburgh University.

1808: Presents the first geological map of the whole of Scotland to the Geological Society of London.

1810: Professor of Natural Philosophy at Geneva University, where he retains a chair for over two decades.

1821: Publishes “Travels in Scotland: Descriptive of the State of Manners, Literature and Science”.

1832: Publishes “Observations on some remarkable optical phaenomena…”.

1841: Settles in Portree on the Scottish island of Skye.

November 20, 1861: Dies at Portree.

Louis Albert Necker de Saussure came from two incredibly high-achieving Geneva families.

On his father’s side: his father was Jacques Necker, a professor of botany at Geneva University and son of mathematician Louis Necker (1730-1804) who made a fortune on the money markets of Paris and Marseilles.

His grandfather Louis’s brother was Jacques Necker (1732-1804), finance minister of Louis XVI, a post he held in the lead-up to the French Revolution in 1789.

Their father was Charles Frederick Necker, a native of Küstrin in Neumark (Prussia, now Kostrzyn nad Odra, Poland), who settled in Geneva where he was elected professor of public law.

In 1764, his great-uncle Jacques fell in love with Suzanne Curchod, a pastor’s daughter from Lausanne who had been engaged to English historian and politician Edward Gibbon. Necker married her before the end of the year and their daughter, Anne Louise Germaine Necker (1766-1817) became an author and wit renowned across Europe under the name Madame de Staël.

On his mother’s side: his mother was Albertine Necker de Saussure (1766-1841), a Geneva-born pioneer in the education of women. She also wrote a biography of her friend and cousin by marriage Madame de Staël (see above).

Albertine was daughter of Horace-Bénédict de Saussure (1740-1799), a Geneva aristocrat, physicist and third man to reach the summit of Mont Blanc. He is often considered the founder of modern mountaineering for initiating the first successful climb of Mont Blanc (by Jacques Balmat and Michel Paccard) in 1786. He appeared on the Swiss 20-franc note from 1979-2000.

Her brother, Nicolas-Théodore de Saussure (1767-1845), became a noted chemist and researcher into plant physiology.

Horace-Bénédict’s grandson was Henri Louis Frédéric de Saussure (1829-1905) a mineralogist and Honorary Fellow of the Entomological Society of London who had nine children, including the linguist and “father of semiotics” Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913) and Esperantist René de Saussure (1868-1943).

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!