Give me your blood and I’ll map your origins

A DNA sample is all you need to pinpoint a person's European ancestry down to their home country, a study has shown.

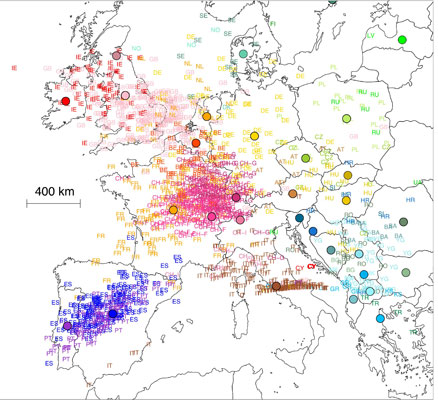

A team of Swiss and American researchers used DNA to predict the geographic origins of individuals from a sample of Europeans, creating a genetic map with a remarkable degree of accuracy – often to within a few hundred kilometres.

By analysing single-letter DNA differences in the genomes of 1,387 Europeans, experts could tell a Brit from a German, or even a Swiss German from someone from French-speaking Switzerland.

The study, which was published in a recent edition of Nature magazine, could have important implications for understanding the role of genes in complex diseases, for forensics, the study of recent human history and the development of affordable genetic ancestry testing.

“I don’t really think anyone anticipated that using genetic information would give us such detailed information about people’s origins,” Toby Johnson, a researcher at Lausanne University, told swissinfo.

“For half of the cases we managed to localise the origins of individuals to within a 300km radius on the basis of the genetic profiles available. For the Swiss we even managed to find which of the three main language regions they came from.”

Mathematical process

The team discovered the gene-geography pattern by analysing hundreds of thousands of genetic points known as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)— minute sequence variations in DNA – among samples originally collected by the pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline to help hunt genetic variations that influence the effectiveness of drugs and their side effects.

The researchers focused on individuals whose grandparents were all believed to have come from the same country. They recorded the country of origin for each subject, as well as that of their parents and grandparents.

The scientists then developed algorithms to create a two-dimensional map with individuals positioned according to how similar or how different they are from all the others. When colour-coded to show where each of their grandparents is from, the results clearly show the shape and boundaries of Europe.

“We can recognize the Iberian Peninsula, the Italian peninsula, southeastern Europe, Turkey and Cyprus,” said John Novembre, a population geneticist at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“Despite low average levels of genetic differentiation among Europeans, we find a close correspondence between genetic and geographic distances.”

Not surprising?

The map was so accurate that when a geographical map was placed over their gene map, half of the genomes landed within 310 kilometres of their country of origin, while 90 per cent fell within 700 km.

In many respects, the results are not at all surprising, said Johnson.

“With hindsight it’s kind of obvious that there’ll be relatively little migration and intermarriage across the language groups and potentially more between say French-speaking Switzerland and France,” he said.

It was also well established that the farther apart two people’s origins, the more different their genes will be.

“All the results we see are intuitively plausible, but the surprising thing is to actually be able to see all that information in the genetic data we had,” he said.

Long-term developments

The scientists say that the study’s results have numerous long-term practical implications.

“Investigators now have the potential to get detailed information about a person from a small amount of DNA from a crime scene or unidentified body,” he said.

And ultimately this kind of research should also make genetic ancestor tracing much more affordable and accurate in the future.

But the Lausanne scientist is happy to leave that to others.

“For us this is a stepping stone to figuring out the genetic basis of common human diseases and potentially leading to new discoveries about mechanisms of heart disease and blood pressure regulation,” said Johnson.

swissinfo, Simon Bradley

DNA, or Deoxyribonucleic Acid, is the genetic material of nearly all living organisms on Earth and, as such, can be called the basic building block of life. In 1953, James Watson and Francis Crick unveiled their discoveries about DNA and the double helix model, which formed the basis of genetic coding.

DNA is located in the cell nucleus as the basic structure of the genes, and is composed of two strands of nucleic acid made up of units called nucleotides, wound around each other to form a double helix shape.

The DNA molecule can make exact copies of itself by the process of replication, thereby passing on hereditary information – so determining all physical traits. This enables DNA to be used to identify gender, hair and eye colour, and other genetic markers such as common ancestry.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.