Gold sourcing and Switzerland in focus at the Human Rights Council

As the latest session of the Human Rights Council got underway at the United Nations European headquarters in Geneva, illegally-mined gold came up in multiple discussions, with the role of importers, including Switzerland, being cited in UN findings.

Last week, a special rapporteur investigating the use of mercury in small-scale gold mining and a UN fact-finding mission on Venezuela presented separate reports to the council on the impact of gold mining on many communities and the environment, particularly in the Amazon basin.

UN investigators cited human rights abuses such as sexual exploitation of women and children, mercury poisoning and child labour affecting communities where illegal gold production occurs, and pointed the finger at the responsibility of countries buying the metal.

The reports said global buyers such as Switzerland – through which roughly two-thirds of global trade transits – need to ensure that human rights are respected throughout supply chains.

Insatiable demand and a lack of due diligence

“This is a serious issue,” Marcos Orellana, the UN’s special rapporteur on toxic substances, who investigated human rights abuses in small-scale mining, told SWI swissinfo.ch. “In the coming months and years, we can expect further scrutiny by human rights mechanisms of the gold sector and of countries where refiners are located, including Switzerland.”

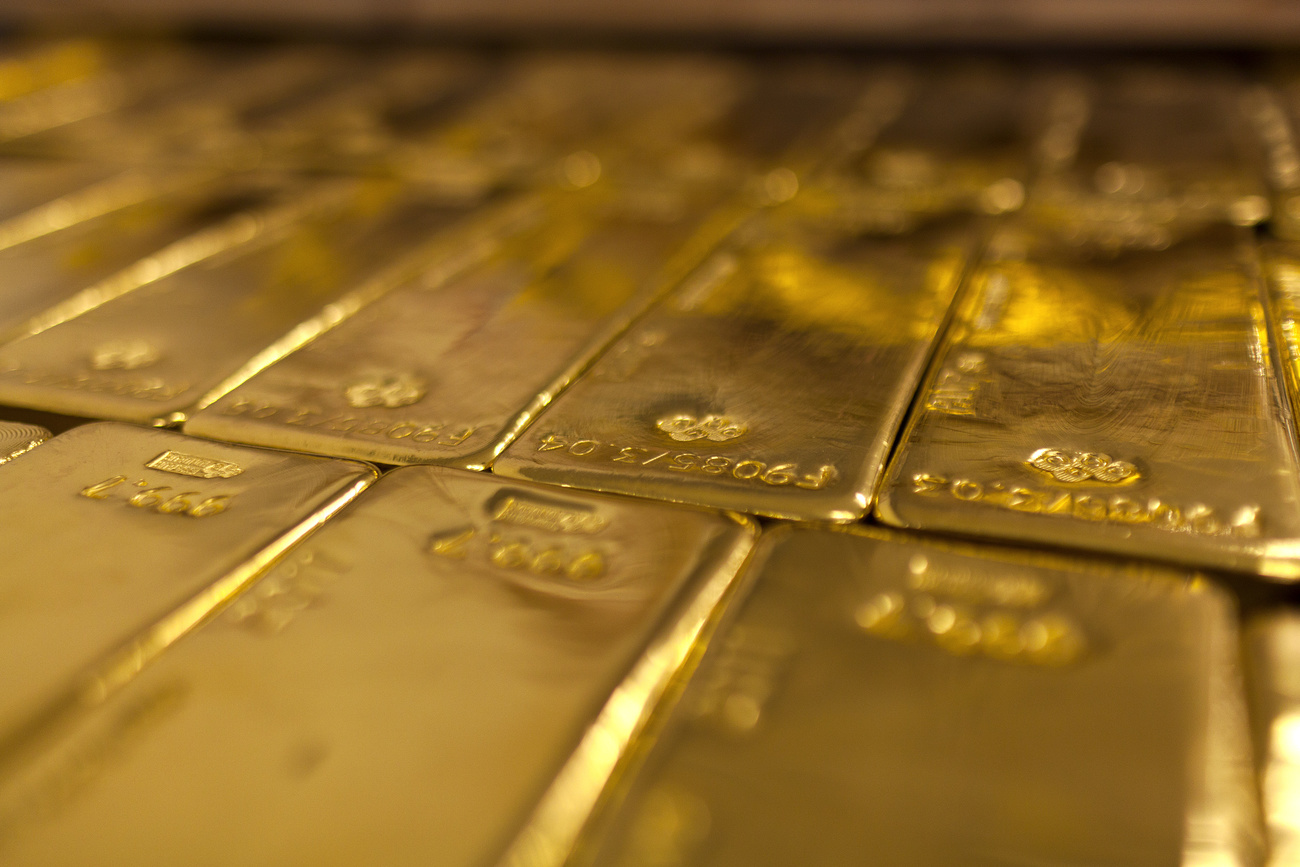

Switzerland is the top global importer of gold, having purchased CHF90 billion ($92.3 billion) of the metal in 2021. Four of the biggest refineries globally are located in Switzerland, two of which are foreign-owned.

In 2020, the Reuters news agency estimated that three of the top refiners – Valcambi, Argor-Heraeus and PAMP – refined roughly 1,500 tonnes of gold annually.

Orellana described to the Human Rights Council last Tuesday how pregnant women in Indigenous communities living downstream from gold mining in the Bolivian jungle had high mercury blood levels due to consumption of contaminated fish, while sexual abuse and violence was prevalent in mining areas. The reportExternal link describes how even on Pacific islands, thousands of kilometres from gold mines, elevated levels of mercury were found in residents, due to global contamination in oceans.

According to the UN, some 10 to 15 million people were directly employed in small-scale gold mining globally in 2017, including roughly a million children and 4.5 million women.

Mercury, which is used to separate the gold from other substances, is a highly toxic heavy metal, that bio-accumulates in living beings and can cause permanent damage in humans including neurological disorders, reproductive disorders and death.

“The use of mercury is propelled by the insatiable demand for gold by financial markets and jewelers in the wealthiest countries,” Orellana told the Human Rights Council assembly. “Refineries in industrial countries which buy the gold lack adequate mechanisms for due diligence to address the human rights abuses associated with mercury and small-scale gold mining.” The report singled out by name Switzerland and the United Kingdom, which in 2020 topped the Alpine nation in terms of gold imports.

Speaking to SWI by phone after his exposé, he said that Switzerland needed to do more.

“Switzerland… does not have an adequate traceability system that would require refineries to know where the gold came from and how it was mined,” Orellana said. “The traceability system that Switzerland has ends with the intermediary country. This gap is exploited by criminal syndicates and drug cartels that traffic in mercury and gold.”

“While the gold industry profits, human rights suffer,” he added.

In Peru’s southeastern Madre de Dios region, SWI previously reportedExternal link how nearly 1,000 square kilometres of rainforest had been lost, as illegal miners sold their gold to buyers, including allegedly in Switzerland, willing to turn a blind eye.

Following Orellana’s presentation to the council, more than 40 countries participated in an interactive dialogue on measures needed to reduce human rights abuses in small-scale mining. The Swiss mission was not one of them.

Paola Ceresetti, a spokesperson for the mission, later responded to SWI’s request to comment following the publication of the report. “In Switzerland, the gold trade is controlled by one of the strictest legislations in the world. The law on the regulation of precious metals and money laundering in particular aim to ensure that gold handled by refiners does not originate from fraudulent sources,” she wrote in an email.

Venezuela’s gold abyss

According to another related report to the Human Rights Council, armed violence between sindicatos – criminal groups controlling mines – as well as labour and sexual exploitation, and horrific punishments through arbitrary justice, are rife in Venezuela’s gold mining region. The area known as the Arco Minero was created specifically to mine resources as the country’s economy slid, with the hope that it would attract foreign investment. Residents as well as miners were often “caught in a crossfire of violence in the struggle to control gold,” Francisco Cox, a member of the fact-finding mission told journalists.

The report will be presented in session today to the Human Rights Council.

Cox said non-state actors, such as the sindicatos, as well as authorities, including military and civilian leaders, which hold financial interests in mining operations, were responsible for killings, extorsion, corporal punishment and gender-based violence.

While official data is sparse and lacking in transparency, various reports estimate that between 70-90% of gold sourced from the mining region is illegally produced, Cox said.

The Venezuela report recommended that countries importing gold adopt measures to prevent gold laundering as well as money laundering from the gold sourced in Venezuela’s mining regions.

Official Swiss data shows that the country stopped importing gold directly from Venezuela in 2016. But since then, there has been concern that gold could wind up in Switzerland after transiting through other countries.

Venezuela’s mission to the UN in Geneva did not respond to a request by SWI to comment on allegations of collusion and involvement of authorities in the gold trade.

Transparency on trial

As pressure mounts on importers of gold to ensure cleaner sourcing, Swiss refiners recently responded by pledging to remove all gold originating in Indigenous lands from their supply chains. In 2020, Japanese-owned Neuchâtel-based Metalor said it was halting purchases from artisanal mines.

Swiss data nonetheless show that large volumes of gold are imported from non-producing countries, including in the Middle East and Europe, begging the question of where the gold originates.

Many are pushing for answers.

The Society for Threatened Peoples, a Bern-based NGO, is awaiting a decision in the coming months from the Supreme Court, following its request submitted in 2018 to the federal customs authority to publish files relating to the exact origin of gold imported into the country, arguing that was is in the public interest to know. STP has long investigated illegal gold production in the Amazon and its links to Swiss refiners.

Edited by Virginie Mangin

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.