How the Swiss have navigated crisis (mis)communication during Covid-19

From red and pink posters in public squares to ministers’ frequent appearances on the nightly news, officials in Switzerland have worked hard to gain control of communication about the pandemic. Has effective messaging helped flatten the curve?

“We must act as quickly as possible but as slowly as necessary.”

It’s no accident that this statement by the minister responsible for health, Alain Berset, as he announced the government’s lockdown exit strategy in April landed not just on the pages of newspapers but also on a t-shirt sold to raise money for charity.

The message was a perfect example of the clear, measured and earnest tone that the country’s authorities have tried to strike publicly from the start of the coronavirus outbreak.

“It was received positively all over the country,” said Regula Hänggli Fricker, a professor of mass media and communicationExternal link at the University of Fribourg.

Clarity, consistency and transparency are all key ingredients of crisis communication, she added, “especially when trust is as important as [it is] in this pandemic”.

Indications so far are that the government has gained effective control of communication during the pandemic. Public trust in government reached over 60%, according to a recent poll, and the decline in the number of new cases has allowed the country to pursue a gradual easing of confinement measures.

Yet, at the start of the pandemic, it appeared as if the odds were stacked against the country and any response its leaders might muster. Switzerland, densely populated and sharing a border with Italy, one of the epicentres of the pandemic in Europe, quickly became one of the places most affected by the Covid-19 outbreak.

When it announced measures to fight the virus, the government put the onus on individuals to adhere to them. Staying at home was a recommendation, not a requirement. Messaging would need to be convincing for its strategy to work – not a minor task for a federalist state governed by seven ministers from four different parties taking on the country’s biggest crisis since the Second World War.

One of the best prepared for a pandemic

Mere months before the novel coronavirus became headline news, a comprehensive report found that no single country was fully prepared to face a pandemic. The Global Health Security IndexExternal link, which assessed countries based on several indicators, ranked Switzerland 13th out of 195 states in its preparation.

More

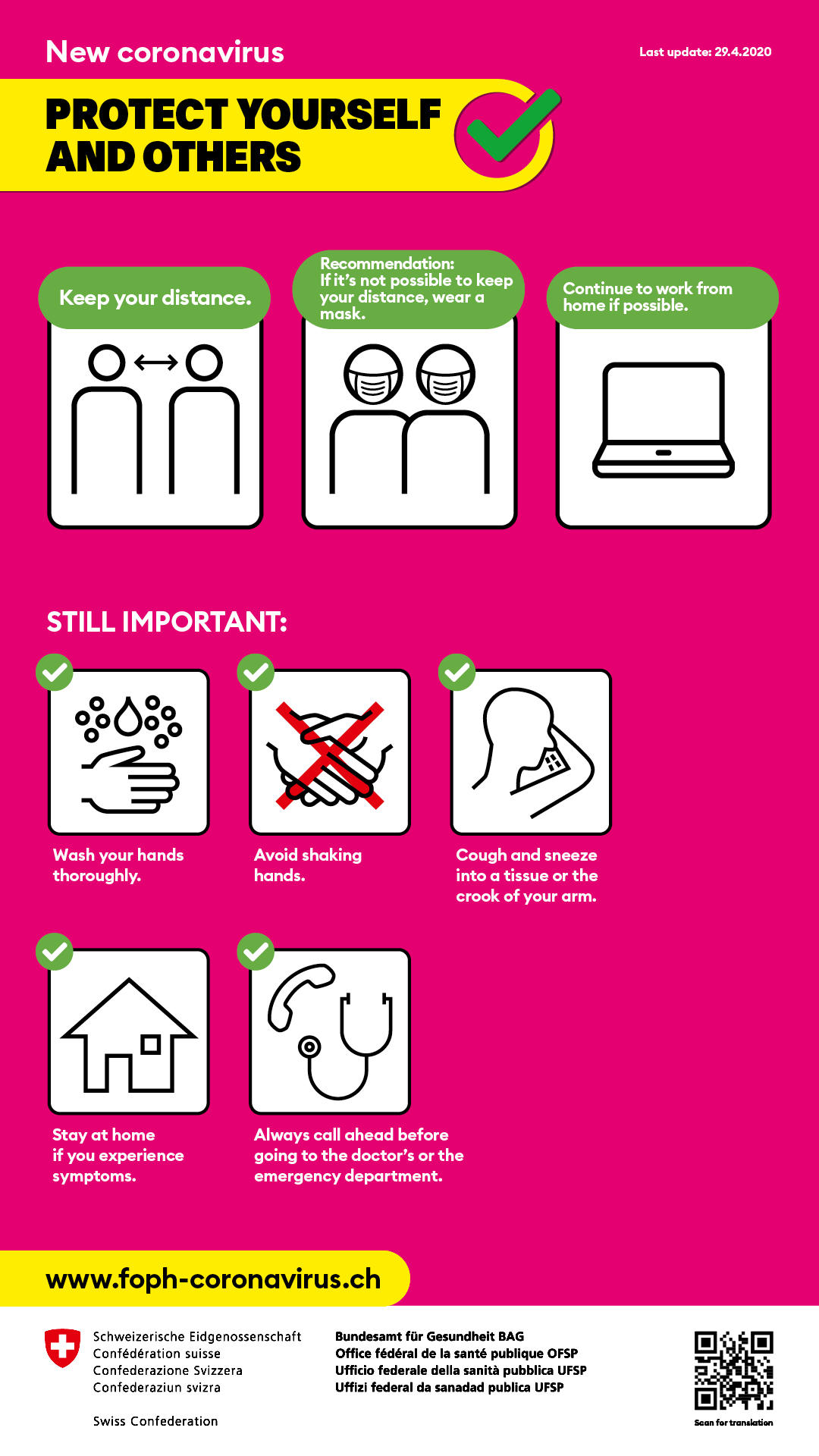

Swiss health authorities unveil new campaign to tackle coronavirus

The Alpine nation scored well (67 out of 100) for response: in addition to a 128-page influenza pandemic response planExternal link, it had “communications plans in place […] and they include clear descriptions of roles and responsibilities”.

In other words, the basic groundwork for crisis communication was already laid when the first case of Covid-19 was reported on February 25. Earlier that month, the federal government’s spokesperson, André Simonazzi, had even created a Covid-19 communications taskforce to coordinate messaging among all the departments.

Until the first case was reported, information regarding the virus was issued by the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH). Afterwards, official communication moved to the Federal Council, Switzerland’s cabinet. With an outbreak now imminent, the public needed not just scientific information, Simonazzi said, but to hear from its leaders about how the country would respond.

“From the start, the government’s main goal has been to protect the population against the coronavirus,” the spokesperson added. Authorities shared information about the virus through a variety of channels, from a dedicated websiteExternal link to social mediaExternal link.

By February 28, the government was acting under the terms of the Epidemics Act for the first time, which allowed it to limit some of the powers of the 26 cantons, which are responsible for health matters, and introduce far-reaching measures, including banning large gatherings.

Trying to speak with one voice

With unprecedented measures in place to fight the virus, the government decided against making social distancing measures like staying at home a requirement, as neighbouring countries like France and Italy had done.

Andreas Ladner, a professor of communication and public opinionExternal link at the University of Lausanne, said it was Switzerland’s way of telling the public, “we’re counting on you”.

“It’s about making people part of the solution to the problem.”

Hänggli Fricker of the Univerity of Fribourg singles out the solidarity campaign “Wir/Nous/Noi/Nus”External link (“we” in the four national languages) as a particular success.

“One important aspect was the feeling of ‘we are all in this together’ when the ‘extraordinary situation’ was declared [on March 16],” she said, adding that President Simonetta Sommaruga made a point of expressing the government’s support as she appealed to everyone to follow the measures.

Somewhat surprisingly, the government chose to communicate through all seven cabinet ministers, plus an array of experts in public health, economics and border management, among others.

More

Did the Swiss stay at home during the coronavirus lockdown?

Those were risky strategies, according to Ladner.

“It’s not what you usually read about crisis communication, where you try to channel communication because you’re afraid of people contradicting each other,” he said.

Between February 28 and May 20, the Federal Chancellery held 46 press conferences about the coronavirus – just under half of them consisting of government ministers and the rest featuring experts, and all of them live-streamed. The method, according to Ladner, appears to be for each expert and minister “to stay close to what they know and what the truth is”.

“The press conferences seem straightforward [and about] providing information honestly,” he added. “It’s not a show they organised.”

The ministers and experts have also made regular appearances on one of the most popular sources of information for many Swiss – evening news programmes on public television channels. Consumption of online news media went up as the pandemic hit in March; major outlets like Le Temps and the Neue Zürcher Zeitung saw traffic doubleExternal link.

Learning from mistakes

But avoiding contradictions and inconsistencies was nearly impossible given that much about the virus is still unknown.

“In the case of the role of children [in spreading the virus], the wearing of masks, the gradual easing of measures, and short-time work – there were uncertainties,” Hänggli Fricker said. “But even though these uncertainties occur, the government sticks to what has been communicated before.”

Re-opening schools after eight weeks of remote learning was a controversial decision. The scientific evidence that children are not important vectors of Covid-19, as officials claimed, was still emerging and did not appear to convince all parents. Yet the government remained steadfast in its decision to send children back to school. Its delegate on the pandemic, Daniel Koch, reiterated assurances that the risk of children spreading the virus was low.

“If they say you can start school, they have to get people to believe it’s doable,” said Ladner. “To say we don’t know is not a good strategy in the long term.”

The authorities have also shown a willingness to admit mistakes and clarify their position, according to Hänggli Fricker. Justice minister Karin Keller-Sutter, for example, conceded she and her colleagues bungled announcements about when restaurants and bars could re-open. These establishments were not part of the original lockdown exit strategy, a move the government later had to revise.

Federalism not an obstacle

Inconsistencies also appeared in the number of new cases reported early in the pandemic by the federal authorities and the cantons.

“The lack of uniform data systems led to problems in communication,” Hänggli Fricker said, adding that this should be a lesson learned.

More

Chasing the numbers behind the virus in Switzerland

Different counting methods aside, the Federal Chancellery tried to coordinate the government’s messages with the cantons, according to Simonazzi. The actors were already familiar with the approach: since 2015 they have all taken part in yearly crisis communications workshops.

“Federalism is a chance,” said Andreas Ladner. For the most part, the system has made good use of the traditions of debate, consensus and unity to find solutions for the cantons, some of which have been more seriously affected by the virus than others.

The federal ministers also made a point of commending the whole population and trying to unify the country – it was thanks to people’s discipline, they said in April, that hospitals had not been overwhelmed and the country could plan the re-opening of schools and businesses.

Nevertheless, messages have sometimes gotten crossed. Early in the crisis the small canton of Uri ordered people over 65 to stay at home, and canton Ticino, then the region with the highest number of coronavirus cases, decided to shut factories and production lines temporarily. None of these measures appeared in the government’s Covid-19 ordinance.

Ladner, though, said authorities had other challenges to deal with, such as how to convince those living in cantons where comparatively few cases had emerged to adhere to lockdown measures.

Respected experts and figureheads

Part of ensuring credibility and cooperation from the public is establishing the authorities as reliable sources of information on the virus.

Daniel Koch, the head of infectious diseases at the public health office and Covid-19 delegate, has appeared frequently before the media to provide updates on the situation. His unruffled, measured tone and medical background earned him early praise in the media, even if he has faced tough questioning on issues like wearing masks and the role of children – topics that continue to divide the Swiss population.

The government also appointed a scientific task force to offer evidence-based advice and analysis. And it called on various federal department officials to appear at press conferences to detail measures ranging from border controls to deploying the army to support health care workers.

Communications teams have also gone after online misinformation, responding each time rumours or false claims make the rounds or even appear in the news media, according to Simonazzi, who has posted several tweets to denounce Covid-19 disinformation.

#CoronaInfoCHExternal link Die Meldung der Handelszeitung, dass die Schweiz die Grenzen zu Italien schliesst, ist falsch. Auch die Meldung, dass der Bundesrat heute Abend eine Krisensitzung einberufe, ist falsch.

— André Simonazzi (@BR_Sprecher) March 10, 2020External link

Despite all of these efforts, however, there is one small segment of the population officials have not managed to convince: the hundreds in cities like Zurich and Bern who have protested in recent weeks against the government’s measures. But as one expert, Sebastian Dieguez, told swissinfo.ch, demonstrators who trade in conspiracy theories will not change their minds, no matter what the government says or does.

The majority of the Swiss, though, appear to have largely followed the government recommendation to stay home during the lockdown, the data shows. But without a thorough analysis, both Hänggli Fricker and Ladner said it was difficult to know for sure if effective messaging has helped to flatten the curve. They did agree that overall, the communication strategy appears to have been a good one.

“It’s been quite a complex situation and they’ve managed to cope well,” said Ladner.

The key now is for the government to accompany the public in the relaxation of measures, “keeping in mind there is still a danger [in new cases emerging] but showing they are observing the situation.”

More

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.