How the private sector finances development aid

Switzerland wants to engage the private sector more closely in development cooperation abroad. How exactly does this work?

With its new international cooperation strategy 2021–2024, Switzerland aims to involve the private sector more closely in development projects. The proportion of co-financed projects should double from the current 5% by 2024. The goal is to mobilise additional funds needed in order to achieve the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals of the 2030 Agenda.

“It’s all about jobs,” said Georg Farago, spokesman for the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA). “Nine out of ten jobs in developing countries are created by the private sector. Without a regular income and without work, there is no way out of poverty.” This is why the private sector has a role to play in international cooperation argues Farago.

According to the new head of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), Patricia Danzi, private sector involvement in development aid is requested by developing countries themselves so they don’t need to be dependent on assistance forever. As Farago explained: “By bringing in the private sector, the solutions can continue to exist even after the aid operation has ended.”

How do the funding models work?

Involving the private sector in public development aid is a global trend. Bright minds from various disciplines have long been thinking about how to shed the old models. One of them is Fritz Brugger from the NADEL Centre for Development and Cooperation at the Swiss federal technology institute ETH Zurich.

“The mobilisation of private funds can be roughly divided into three categories,” said Brugger. These are direct investments in the form of loans and equity, guarantees and insurance, and outcome-based payments.

According to FDFA spokesman Farago, in addition to traditional models, in which the SDC jointly carries out and co-finances a project with private partners, there are also projects that take a blended finance approach. This entails the use of public funding to encourage private sector investment. “The basic principle of blended finance is to support investments that are effective but wouldn’t typically attract investors,” said Farago.

Example of the ICRC

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) makes use of public-private partnerships (PPPs), called humanitarian impact bonds, in order to run rehabilitation centres for people wounded in conflicts. “We can’t do this alone,” an ICRC staff member explained in a video. “We need the help of the private sector and new partners.”

The way it works is that private investors help finance projects. After five years, so-called outcome funders like donor countries help the ICRC pay back the investors, based on how successful the project has been in helping people. Investors receive a return if the project has a positive impact but can also make a loss. Switzerland serves as an outcome funder to the tune of CHF10 million ($10.9 million).

“This idea is revolutionary for me,” said Professor Raymond Saner, a former ICRC delegate and co-founder of the Centre for Socio-Eco-Nomic Development (CSEND) in Geneva. “I’ve never heard of a private sector investor being interested in something like this, perhaps as a donor, but not as a capital provider for hospitals. This only works because the ICRC, thanks to public funds, can guarantee companies a certain return on investment, for the risk of having got involved in a humanitarian project.”

Example of the development banks

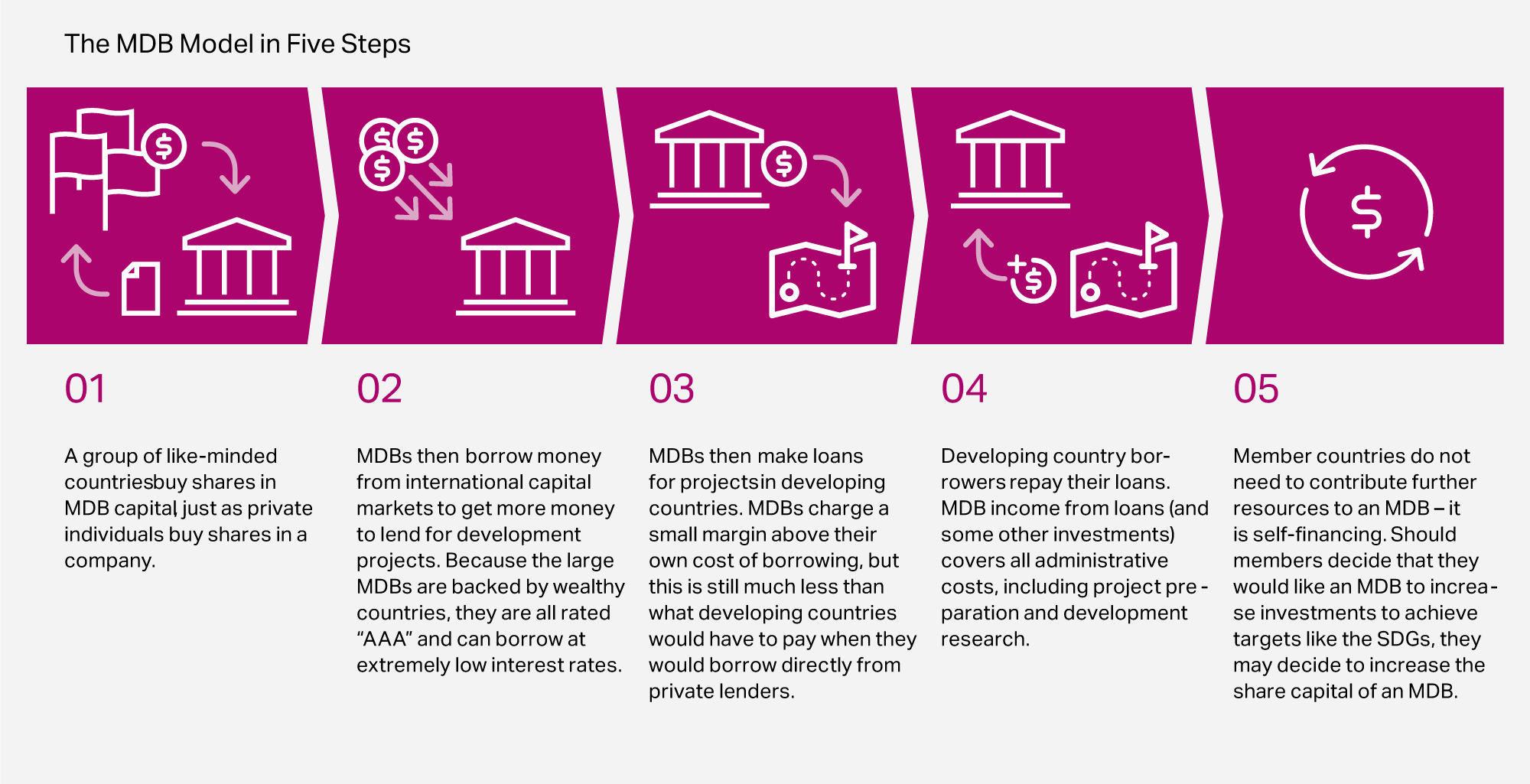

Multilateral development banks are another example of how countries can mobilise private money. These are government-backed banks that grant loans to developing countries, which “normal” banks would refuse to do because of the risks involved.

To refinance the loans, development banks – which enjoy good ratings due to the wealthy countries backing them – raise large amounts of funds on the international capital markets. In this way, public funds help increase private sources of funding in projects.

Switzerland is involved in various multilateral development banks in addition to its own funding institution – the Swiss Investment Fund in Emerging Markets.

“People First”

Involving the private sector in development cooperation remains controversial. Some donor countries have had mixed experiences. “At the beginning, PPPs were mainly about ‘value for money’; investors wanted to make a profit,” said Saner. This led to corruption in some cases, or simply to infrastructure projects without clear development objectives.

This has led governments and the private sector to consider new forms of partnerships. The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) has developed the concept of people-first public-private partnerships (PfPPPs). The idea is that PPPs should be embedded in the 2030 Agenda goals; that is, they should also entail a social and environmental investment.

Saner, who is himself a member of the UNECE Bureau, explained: “So now there has to be a ‘value for society or people’; that is, PfPPP infrastructure projects should clearly also benefit society and the environment.”

Monitoring results

But how can you ensure that people really do come first, and that the slogan is not mere window-dressing?

“Through evaluations,” said Saner.

Projects funded by the Swiss government are evaluated by independent experts in accordance with the international criteria of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. According to FDFA spokesman Farago, the SDC is also planning a major institutional evaluation of private sector involvement in aid in the period 2021–2022.

More

The risky business of foreign aid

“I haven’t seen many of these evaluations so far, though”, said Saner.

There is no obligation to make the results of evaluations publicly available. “Generally speaking, there are only sporadic project evaluations,” Saner lamented. “But without systematic evaluations, we don’t know what lessons to draw from the major projects co-funded by Switzerland.”

“For example, questions like: What was successful? What could be done better? These questions remain unanswered,” said Saner.

Adapted from German by Julia Bassam.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!