Identity at stake in war of words

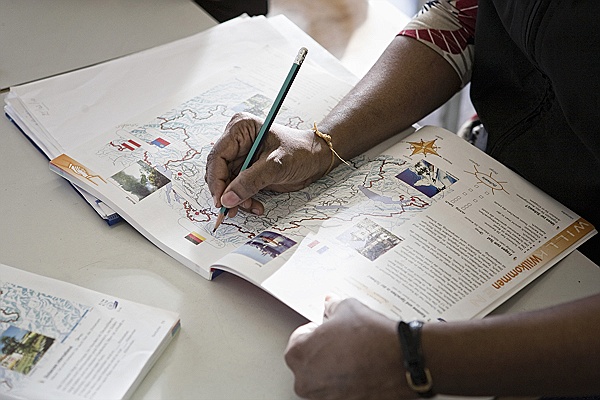

The vexed question of language is back in the news as voters in canton Zurich accepted an initiative to make Swiss German the language of the kindergarten.

At the moment, one third of teaching is supposed to be in dialect, one third in “high German”, the standard language of Germany, and the other third at the discretion of the teachers, according to the situation.

Supporters of the “Yes to dialect in the kindergarten” campaign suspected that the aim of the education authorities was to replace dialect altogether.

There is a real problem: the language spoken by Swiss Germans in the home is quite different from high German. There are many differences of grammar and vocabulary, and to most people who know only high German it is unintelligible.

Yet high German is used in most writing and in formal situations. It is also the language learned at school by other Swiss.

It is generally accepted that Swiss German children need a command of both. But how is this to be done, and at what stage?

Laying the basis

Allan Guggenbühl, a professor of psychology, is a supporter of the Zurich initiative.

“It is widely accepted throughout the world that if one wants to help increase competence in talking, one has to start with the language that is actually talked, and not with a language which is alien,” he told swissinfo.ch.

“The goal is language competence in high German, and in Swiss German. The question is how to get there. You get there a lot better and a lot quicker by helping them to learn one basic language. And once they know that language, they can move on,” he explained.

High German is everywhere, including on television, so even very small children are exposed to it, which is a good thing. But if children are to become proficient in languages, the best thing is to wait until they go to school at the age of seven before learning them actively, he said.

Language proficiency

Sunday’s vote has returned the situation to how things were before 2008. But did that really produce the desired language skills?

Iwar Werlen, professor of general linguistics at Bern university, told swissinfo.ch that on the whole Swiss Germans prefer to use French or English rather than high German when dialect is not an option.

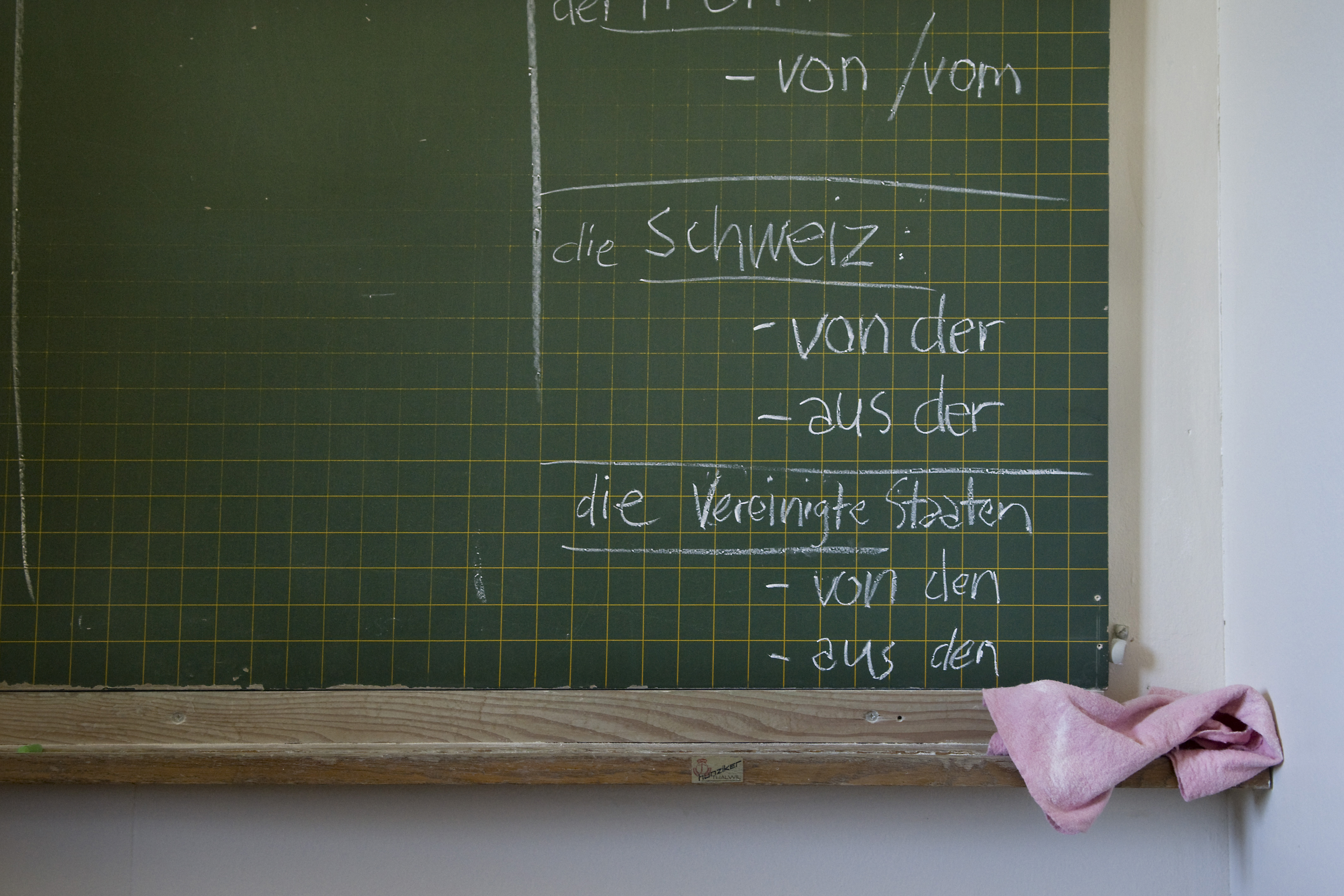

“To some extent that has to do with the fact that in schools high German is used a written language, and people haven’t really learned to speak it in daily situations,” he explained.

“There’s also the fact that although the Swiss don’t really like the Germans, they admire them for speaking ‘better’ high German. They think that they’ll never speak so well, so better not to speak at all.”

That was one reason why the cantonal directors of education decided to promote the speaking of high German in schools. They do not have jurisdiction over kindergartens, but some cantons were inspired by the ruling to introduce some high German at that level as well.

“The basic idea was that more high German should be spoken in school, so that people get used to speaking it, rather than simply reading and writing,” he explained.

Switching

And for him, the sooner children start, the better.

“There has been research done in test kindergartens, in Basel, and in Liestal, which found that children have no problem in switching. Most already know some high German from television, and then they simply use it. And it they don’t know the high German word they’ll use the Swiss one, and it’s just fun for them, and not a problem.”

It is up to the teacher to make a clear distinction between the two languages, to ensure that they do not get confused. “What’s difficult for the children is if the teacher changes from one language to the other without any reason,” he said.

Guggenbühl stressed that if children are to get a good language grounding, Swiss German needs to be taught: it has its own grammar and vocabulary and expressions, and teachers have to pay attention to this.

But Werlen says that even in teacher training institutes there is no discussion of the nature of dialect among dialect speakers – and that this is a major lack. But efforts to promote it have “fallen on deaf ears”.

Integration and cohesion

An pro-dialect initiative underway in canton Lucerne uses a picture of a child with its face painted like a Swiss flag.

“Swiss German plays a central role in the integration of foreigners,” says its website.

“In Switzerland you are only accepted if you speak Swiss German,” Guggenbühl told swissinfo.ch. “If you speak high German, you are not accepted.”

That may be true in the German-speaking area, but Switzerland has three other national languages.

Forum Helveticum, an independent association promoting debate about issues of public life, a few years ago published a study on Swiss German, local identity and national cohesion.

“The conclusion was that local identity is very important, so it’s true that dialect has to be fostered, but national cohesion is also very important,” Forum Helveticum’s director, Paolo Barblan, told swissinfo.ch.

“Many people from the non-German parts of Switzerland say that things have changed over the last 20 or so years. Back then, a Swiss German would automatically switch to high German if the other person did not know dialect. Now they happily continue in dialect, and simply don’t notice that the other doesn’t understand them.”

“One reason why that happens is that Swiss Germans feel much less happy in high German than they used to,” Barblan adds.

Percentages of language speakers from the last federal census conducted in 2000:

National languages:

German 63.7%

French 20.4%

Italian 6.5%

Romansh 0.5%

Non-national languages:

Serbian and Croatian 1.4%

Albanian 1.3%

Portuguese 1.2%

Spanish 1.1%

English 1.0%

Turkish 0.6%

Tamil 0.3%

Arabic 0.2%

Switzerland has four national languages, German, French, Italian and Romansh.

The spoken forms of the German of Switzerland and the German of Germany became differentiated in mediaeval times.

Spoken Swiss German is largely unintelligible in most of Germany.

There are three main German dialect divisions within Switzerland – although each spills over into the border areas of neighbouring countries.

Apart from a slight difference in accent and vocabulary, the French spoken in Switzerland today is similar to that of France and to the written language.

However, the language originally spoken in western Switzerland was not French but Franco-Provençal, which was also spoken in eastern France and northern Italy. It survives, with difficulty, in local patois, which exist in a range of local variations.

Switzerland’s Italian speakers, in Canton Ticino and parts of Canton Graubünden, use standard Italian, but in private many speak a dialect of Western Lombard, the unofficial language of northern Italy. This dialect exists in many local variations.

Romansh, spoken in parts of Canton Graubünden, exists in five distinct spoken forms, known as “idiomas”, each of which also has a written version. The idiomas also have their own dialects. An artificial written language, Romansh Grischun, was introduced as an umbrella form in 1982 and is used for official documents.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.