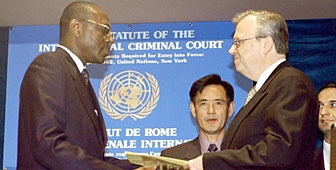

International Criminal Court gets go-ahead

At least 60 nations, including Switzerland, have now ratified the treaty for the International Criminal Court (ICC), meaning that the court can be set up.

The court will be the first permanent body for the prosecution of war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide. It will bring cases when the individual countries concerned are either unable or unwilling to bring prosecutions themselves.

The legal framework for the Court was drawn up at a special United Nations conference in Rome in 1998, when 139 nations signed the statute for the ICC.

But many of those nations, including some of the world’s most powerful, such as the United States, Russia and China, have withheld ratification, apparently fearing that the court’s prosecutions could be exploited for political purposes.

Strong Swiss support

But Switzerland remains one of the strongest supporters of the ICC. Rudolf Wyss, deputy director at the Swiss Justice ministry, says the court will fill a gap in the way in which humanitarian law is upheld.

“The ICC is a permanent institution, and will ensure that crimes against humanity no longer go unpunished,” Wyss told swissinfo. “For me personally the fundamental reasons for supporting the ICC are international solidarity and a deep respect for the rights of all human beings.”

Wyss said that Switzerland had never had any doubts about ratifying the ICC, and had not asked for any particular amendments. France on the contrary did ratify, but asked that its military be exempt from prosecution by the ICC.

“This would be completely unnecessary for Switzerland,” explained Wyss, “because we are a neutral country and our army does not operate outside our borders.”

Wyss also believes that some of the bigger countries which have yet to ratify the court may change their minds once the court proves its success.

“You have to remember that there was a lot of scepticism about the ad hoc tribunals for former Yugoslavia and Rwanda before they got started,” explained Wyss. “But now that they are seen to be working everyone accepts them.”

“I think the same will be true of the ICC,” Wyss continued. “Once it has carried out a few successful prosecutions there will be a lot of moral pressure on those countries who have not yet ratified it to do so.”

Massive atrocities

Human rights lawyers hope Wyss is right. In Geneva, the International Commission of Jurists has been lobbying for years for an international criminal court.

Louise Doswald-Beck, who is secretary general of the Commission, believes those countries who refuse to ratify the court are making a mistake.

“Human rights abuses harm everyone,” Doswald-Beck told swissinfo. Massive atrocities have an impact far beyond the victims themselves. “So even from the point of enlightened self-interest they ought to ratify.”

Doswald-Beck rejects the argument that ad hoc tribunals can be set up whenever human rights abuses are seen to have been committed.

“Between the Nuremberg trials after the second world war and the ad hoc tribunals for Rwanda and former Yugoslavia there were no prosecutions for human rights violations,” she explained, “despite the fact that many atrocities had taken place.”

Overlooked injustice

“The reality is that some cases, like Rwanda and Yugoslavia, get a lot of attention, while others are just forgotten about. What you are left with is a massive sense of injustice on the part of the victims.”

“The ICC has to fill that gap” Doswald-Beck continued. “It must make sure that the very many persons who commit human rights abuses are brought to justice, and that the Geneva Conventions are upheld.”

“We don’t want victims of these abuses to think the world is only interested in ‘real politik’,” she said, “and that no one really cares about their sufferings.”

Now that the ICC has passed the limit of 60 ratifications, it is expected to begin work in January 2003. It will have its permanent seat at The Hague in the Netherlands.

US opposition

The United States had been particularly vocal in opposing the international court, fearing arbitrary prosecution of its citizens. The conservative US Senator, Jesse Helms, launched a strongly worded attack, and has introduced a law, the American Servicemen’s Protection Act, that would forbid US participation in the court. The legislation sponsored by Helms, who is retiring from the Senate after a lengthy career, would impose sanctions and suspend military cooperation with countries that refused to recognise immunity of US soldiers stationed in the countries.

President George W Bush is considering a radical step: withdrawing the American signature from the treaty of Rome which served as the basis for the international court. In addition to the issue of soldiers stationed abroad, the US is concerned about a possible scenario such as the prosecution of a pilot who might fire missiles in a conflict like the Gulf War.

China, Japan and other Asian states have also refused to ratify the treaty for the international court, fearing similar scenarios involving their military or civilians.

by Imogen Foulkes

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.