Ai Weiwei: Art is a way of questioning power

Art is innocent, says contemporary artist Ai Weiwei, but it is also a means of questioning the establishment. The Chinese native was in Lausanne on Wednesday to talk about his life in exile and a new exhibition which has taken over the city’s Palais de Rumine and museums.

“I’m always very grateful to Switzerland as this is where I really started my career as an artist,” the 60-year-old tells reporters. Ai Weiwei’s early work was showcased at Bern’s Kunsthalle in 2004 – his first European solo exhibition.

“I feel I have drawn a circle and the two ends have met. I’m like a Swiss product,” he joked.

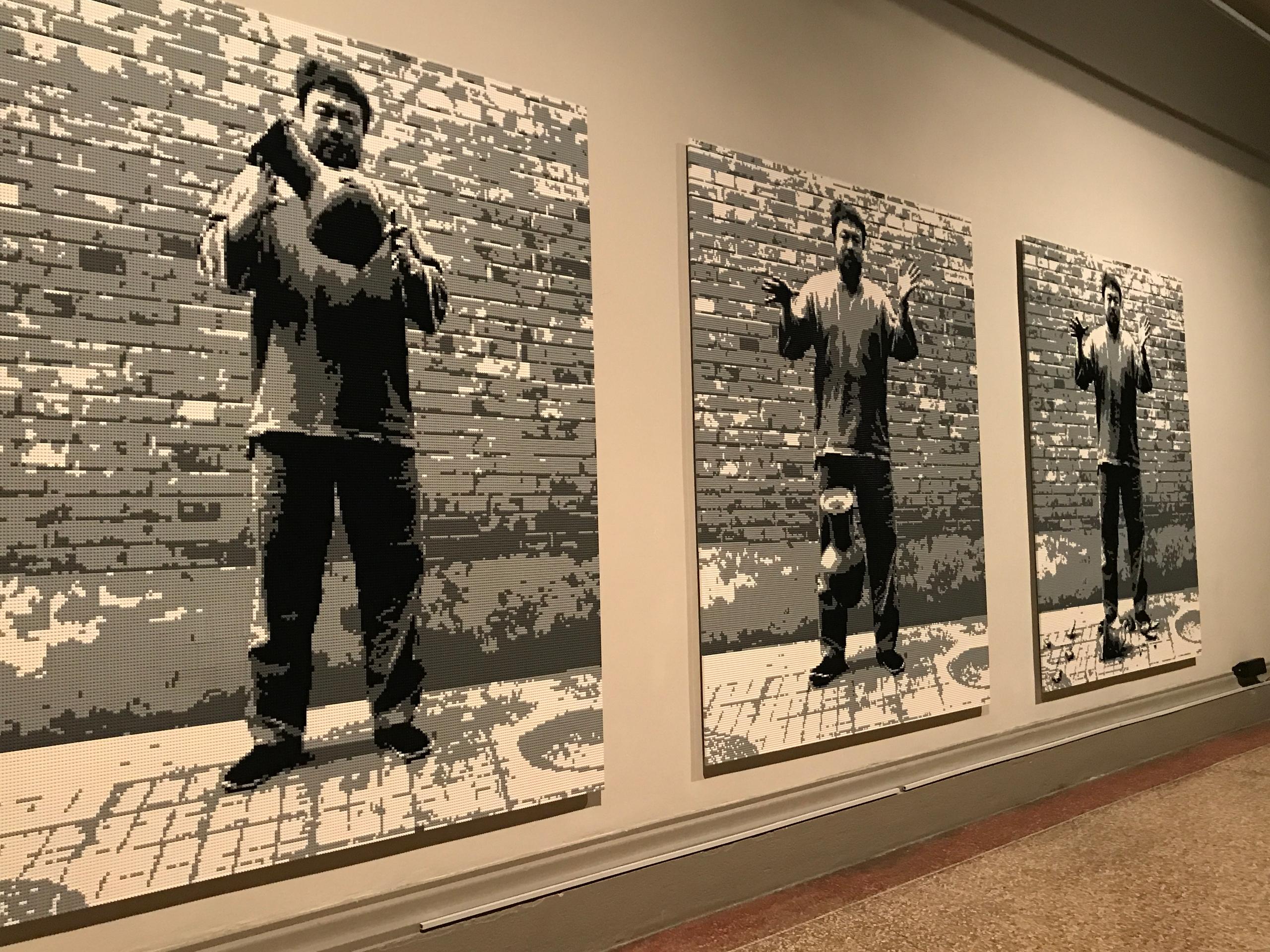

His new exhibition entitled ‘Ai Weiwei. It’s Always the Others’, which runs from September 22 to January 28, 2018, features 46 of his works, many well-known, but in new and often unusual settings.

The Zoology Museum on the top floor of the Rumine building, for example, features a 50-metre-long silk and bamboo dragon suspended over the glass displays of stuffed animals. The artist’s dragon – a traditional symbol of Chinese imperial power – has become a sign of personal freedom, made up of individual kites carrying quotes from imprisoned or forcibly exiled political activists such as Nelson Mandela, Edward Snowden and himself.

New scale

“This is the first time that I’ve tried exhibiting my works in this scale in museums, which are ready made for the purpose, but offer new possibilities,” he declared. His other works are scattered throughout the art, archaeology, geology and coins and medals museums for the public to discover.

The airy Cantonal Fine Art Museum and Renaissance-style architecture provides the setting for one of his more monumental pieces: ‘Sunflower Seeds’ – a carpet of 10 million handmade porcelain sunflower seeds laid out in the middle of the main hall. These are part of the 150 tonnes Ai Weiwei had made by 1,600 artisans in factories in Jingdezhen in China, and which were first shown at the Tate Modern’s huge Turbine Hall in London.

Here they can be admired alongside the spectacular golden trompe l’oeil wallpaper with geometric designs of surveillance cameras, handcuffs and Twitter logos, echoing the difficulties he experienced with the Chinese authorities when he was locked up for 81 days in 2011.

The refugee crisis, which has been the focus of his recent work, including new documentary “Human Flow” which premiered at the Venice Film Festival this month, is less visible in Lausanne. A black marble tyre sitting at the bottom of a fountain inside the Rumine building is a subtle monument to refugees who died in recent sea crossings.

But as a rootless dissident artist who has been living in Berlin, Germany for the past two years since leaving China, the refugee issue is a driving force.

“It’s my personal journey to understand what makes 65 million people push away from their homes and give up everything. It’s important to understand why this happens in the 21st century. What future will all these people have in Europe? Is Europe defending their values? These are serious questions,” he says.

Exile

Ai has travelled back to China only once since 2015 to see his sick mother and says the ‘danger is always there’. His two Chinese lawyers have been imprisoned for the past five and ten years, respectively, and he says he does not intend to put his eight-year-old son through hardship.

“They let me go back and kept their promise. They didn’t touch me. But anything could happen as it’s very unpredictable,” he said.

His battles with the Chinese state have made him the artist he is today. Outside the country, he remains highly critical: “China is powerful economically but does not trust its own people.”

Wrapping up his Lausanne press conference, Ai made a heartfelt plea to support artists.

“Art is probably the most untouched free practice of the individual. Art is innocent. It can protect humans’ precious curiosity, and it’s also a way of questioning power and the establishment,” he declared.

Son of the famous writer Ai Qing, Ai Weiwei was born in Beijing in 1957. In 1983 he moved to the United States, where he discovered art and was influenced by Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol.

Returning to China in 1993, he set about broadening the scope of his work and helping other Chinese artists by curating exhibitions including Fuck Off (Shanghai, 2000) and organising underground publication networks. Imprisoned for his anti-government positions – he spoke out against the concealment of the humanitarian disaster following the Sichuan earthquake of 2008 – and then released in response to worldwide protests, he now lives in Berlin.

His work blends different mediums – sculpture, film, photography – with Chinese craft traditions while parodying Pop Art and American Minimalism. Rooted in tradition, his wide-ranging work mixes sharp political criticism, especially of China, with humour, his private life, and sensitivity to the fundamental elements of the human condition.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.