Life-saving work earns biologist top award

Swiss entomologist Hans Herren is credited with saving 20 million lives in Africa.

When a non-native insect threatened to wipe out the continent’s cassava crop, Herren came up with a natural – and award-winning – answer.

His work has now won him the 2003 Tyler prize for Environmental Achievement.

Herren, who was born in Mühleberg near Bern, was just 31 years old when he took a new job in Africa and landed in the middle of a crisis.

The mealy bug, a non-native species introduced accidentally from South America in the 1970s, was eating its way through the cassava crop.

The root is the staple food for more than 200 million people living along a belt stretching from Senegal to Mozambique.

“Many farmers lost everything,” says Herren, who was working at the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture in Ibadan, Nigeria.

“Some tried to burn whatever small fields they had left to get rid of the insect, but that was not a solution because they didn’t have any planting material. They tried to grow other crops but very often where cassava grows, nothing else does.”

Natural predator

Herren and his team quickly realised that their only hope of checking the mealy bug’s advance lay in tracking down its natural predator.

The only problem was that the solution lay in the area between California and Argentina and nobody really knew where to start looking.

Herren narrowed the search to five key areas where they believed cassava originated, and, against all the odds, the team struck gold.

“At the very beginning I thought it would take years to find the pest and then to find its natural enemies,” says Herren. “But it worked much faster than we thought.”

“Within six months we had found the mealy bug, which was unbelievable. It was like looking for a needle in a haystack.”

Parasitic wasp

Within two years, they also discovered a natural enemy of the pest – a parasitic wasp – in Paraguay, and brought the insect back to Africa for trials. It cleared a field of mealy bugs in the space of three months.

The next challenges were breeding and distribution. Originally, they thought they could train people in different countries to rear the wasps, but time was not on their side – the mealy bug was already out of control.

“Wherever the mealy bug established itself, almost 90 per cent of the cassava was gone, so we didn’t have time to do this small scale,” says Herren.

The team decided to rear millions of wasps in Nigeria and release them out of the back of an airplane – over an area one and a half times the size of the United States.

Within ten years, the wasp brought the mealy bug under control, preventing widespread famine and the deaths of an estimated 20 million people.

It is regarded as one of the largest and most successful biological control programmes in the world.

International awards

The Swiss entomologist’s victory over the cassava mealy bug has won him numerous international awards, including the World Food Prize, the Brandenberger prize and most recently the 2003 Tyler prize for environmental achievement.

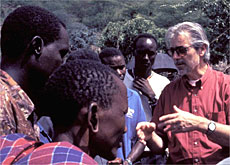

Herren is currently the director of the international centre of insect physiology and ecology in Nairobi, Kenya, and president of the Zurich-based foundation, Biovision, which mediates between scientists running sustainable development projects and local communities in Africa.

His work against agricultural pests continues, using a combination of natural enemies and repellant plants.

The stemborer, for example, is one of the biggest threats to maize cultivation in sub-Saharan Africa.

By planting napier grass – which attracts the stemborer – around a maize field, as well as growing desmodium – which repels the insect – inside the field, the threat can be drastically reduced.

Meanwhile, a project in Ethiopia to combat the tsetse fly – the vector for various fatal cattle diseases – employs the same principle, using odour baits to lure the flies into traps or repellents based on the scents of animals like the water buck that never attract the tsetse fly.

“Africa needs more than subsistence agriculture,” says Herren. “It needs a dynamic and economically viable agricultural sector which will help everything else develop.”

swissinfo, Vincent Landon

Hans Herren identified the natural predator of the mealy bug, which was destroying the staple food of 200 million Africans.

He lives and works in Nairobi, Kenya, where he is director of the international centre of insect physiology and ecology.

He has won numerous international awards including the World Food Prize in 1995 and the Brandenberger prize.

His most recent award was the Tyler prize for Environmental Achievement.

It has been granted annually since 1973 to outstanding scientists by the University of Southern California.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.