Living in the shadow of the concrete giant

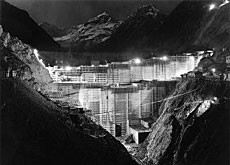

Holding back some 400 million cubic metres of water high above the Rhône Valley, the huge Grande Dixence dam is an imposing sight.

As sirens rang out across the country last week for the annual disaster alarm test, swissinfo visited Sion, in southwestern Switzerland, to find out about levels of emergency preparedness and the dangers of living downhill from the concrete giant.

Perched at over 2,300 metres above sea level at the head of the steep Val d’Hérens valley, the 265-metre-high Grande Dixence is the world’s tallest concrete gravity dam.

Some 15 million tons of concrete were needed to build the spectacular wall, which is almost 200 metres thick at the base, to withhold rain and meltwater from 35 surrounding glaciers that run off into the belly of the beast.

The colossus looks completely watertight and invulnerable, but what if…?

Could a dam breach actually happen? And if so, what would happen to the people living down the valley? Would they have time to react and know what to do?

The chances of an accident occurring are very slim, explained Georges Darbre, responsible for dam safety at the Federal Energy Office.

“We do everything to prevent such an event occurring in terms of the way the dam is designed and constructed… and all the surveillance monitoring measurements,” he told swissinfo.

“And we are very sure it won’t occur, but we know through experience looking at what happens abroad that there is a residual risk.”

The Grande Dixence is one of 247 large dams in Switzerland, out of a total of 1,200, under the authority of the Federal Energy Office. The remainder are under cantonal supervision.

Dam burst

Although they are very rare, dam accidents do occur from time to time. The world’s worst dam collapse occurred in China in 1975 when flooding caused the Banqiao and Shimantan reservoir dams to fail. Some 200,000 people are thought to have drowned or died soon afterwards due to infectious diseases.

And in December 2000 production was put on hold at the Grande Dixence after a high-pressure pipeline from the dam burst, causing a landslide that wiped out a small hamlet and killed three people.

Subsequent investigations showed that the welding carried out by a contractor had failed, releasing thousands of cubic metres of water.

“The mountains are beautiful, supplying us with plenty of water to produce renewable energy – one of the canton’s riches – but they also represent a risk,” said Jean-Réné Fournier, state councillor in charge of safety for Valais canton.

Risk management

Managing this risk involves proper emergency planning and an important element of this is the national alarm system, drawn up by the federal authorities, cantons and communes, said Darbre.

Switzerland’s alarm network consists of around 8,200 sirens – 4,700 stationary, 2,800 mobile and 700 located close to hydroelectric dams – to warn the population in the event of a possible threat. In all, they cover some 98 per cent of Swiss territory.

“In our highly technical and civilised world, which has become more susceptible to disasters, a siren system is essential,” said Willi Scoll, director of the Federal Civil Protection Office.

“Countries like Germany, which has done away with its network, regret doing so and want to rebuild one.”

In the event of a risk of flooding, people downhill from dams are alerted by a “water alert” signal – low continuous 20-second tones at ten-second intervals – and urged to leave the at-risk area immediately and follow local instructions. In theory, they would have two hours to flee before the dam totally collapses.

In the case of the Grande Dixence, residents living downhill had better act swiftly, as icy waters would rush down the mountain at speeds of up to 200 kilometres per hour, say experts.

Prepared for the worse?

“The first waters would hit Sion in four minutes and a second wave would reach the town hall after 11 minutes,” said the Sion mayor, Marcel Maurer, referring to simulations from the 1980s.

Large swathes of the Val d’Hérémence, Val d’Hérens and Rhône valleys would be flooded if the 200-metre-thick wall were to be totally breached, claims the Federal Civil Protection Office.

“But local residents are extremely familiar with the town evacuation plan that has existed for years and each district knows in which direction to escape as fast as possible,” said Maurer.

Unfortunately, not everyone seems that certain of what to do if they hear a wailing siren for real.

“I don’t know… I have no idea,” said 17-year-old Philippe Chappuis at Sion station.

“We were taught that when you heard an alarm you had to head as quickly as possible for the opposite hillsides,” said former Sion resident Karine Zambaz. “But in a worse-case scenario you wouldn’t stand much of a chance, as the roads would be totally blocked.”

According to the Federal Civil Protection Office, only 60 per cent of Swiss people know what to do in the event of an alarm going off.

“This low figure is alarming,” said Scholl. “A significant proportion of the population doesn’t know the correct behaviour to adopt.”

To help reverse the tide, on Wednesday the federal office launched a nationwide awareness campaign, including TV and radio spots featuring the country’s very own blonde sex siren, former ex-Miss Switzerland Christa Rigozzi.

swissinfo, Simon Bradley

Grande Dixence dam: 285 metres high and 700 metres long.

Location: 2,365 metres above sea level.

Weight: 15 million tons.

Holding capacity: 400 million cubic metres of water.

Over 100 kilometres of connecting tunnels.

Current maximum power output: 990 MW.

Cleuson-Dixence potential output: 1,200 MW.

Power is sold to 18 cantons.

In the case of extreme weather, flooding or serious earthquakes, the National Alarm Centre sends the alerts of the Swiss Meteorological Office or the Swiss Seismological Service to the affected cantons, the army, the Federal Police Office and other parties.

The alert to the population is communicated by the 8,200 sirens spread across the country and normally operated by the cantonal police.

The population is then supposed to tune in to the radio stations of the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation for information, follow instructions and inform neighbours. If a water alarm goes off residents are urged to leave the at-risk area immediately and follow local instructions.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.