Lucerne, the capital city that never was

Three times Lucerne tried to be named the capital of Switzerland. Only the first attempt succeeded, short-lived as it was. None of this, however, can overshadow Lucerne’s decisive role in the birth of Swiss democracy.

In 1798, the aristocrats of Lucerne took the unusual step of proclaiming their own overthrow.

“The aristocratic form of government is abolished,” they announced one day in late January. Within a week the first election took place to elect a local parliament. By March 1, the Lucerne national assembly had met for the first time.

The political landscape in Europe in those days was dominated by two opposing systems: revolutionary France on one side, and the conservative alliance of the Austrian, Russian and British monarchies on the other.

France favoured republicanism. Since a committee controlled by the middle class began ruling France in 1795, republics had emerged in the Netherlands and Italy. The existing Swiss Confederation, too, was affected by the winds of change. Subjects of the aristocratic city-states of Bern and Basel rose in revolt. But Lucerne was the first of these oligarchies to fall.

The Helvetic Republic

For 200 years Lucerne had had close military relations with France. The locals were well informed in 1789 when revolution broke out in Paris. The more progressive among the Lucerne nobility wanted to be part of this even if changes were necessary.

France had other aims. It was interested in a direct route to Italy. To ensure this, it would be easier for the French if Lucerne was ruled by a central government – this was the thinking in Paris. So Lucerne’s small republic only lasted two months.

France, having occupied Aarau, called a National Assembly meeting there from all the revolutionary cantons. The assembly proclaimed the first constitution of the Helvetic Republic. This had all been a French idea, but here again it was not really in the interests of France.

Aarau was the provisional capital of this Helvetic Republic. But space was hard to find in the town. After a few weeks the occupying power appealed to a number of Swiss cities to make proposals for a new capital. There were responses from Basel, Bern, Fribourg, Solothurn, Zurich and Lucerne. Lucerne won.

Lucerne as capital

The Helvetic institutions took up quarters in Lucerne. It was now the proud capital of a whole nation, with a flag, fanfare – and francs.

But the joyful feelings did not last. War broke out in Europe again, with the monarchies attacking the French – in some cases directly on Swiss soil, including in Zurich, only 50 kilometres north of Lucerne. The safety of the new capital was in danger. At the end of May 1799 the Helvetic republicans judged it advisable to flee to safer ground. They made Bern their new capital.

This series in several parts is tailored for our author: Claude Longchamp’s expertise makes him the man who can bring alive the places where important things happened.

Longchamp was a founder of the research institute gfs.bern and is one of the most experienced political analysts in Switzerland. He is also a historian. Combining these disciplines, Longchamp has for many years given highly acclaimed historic tours of Bern and other sites.

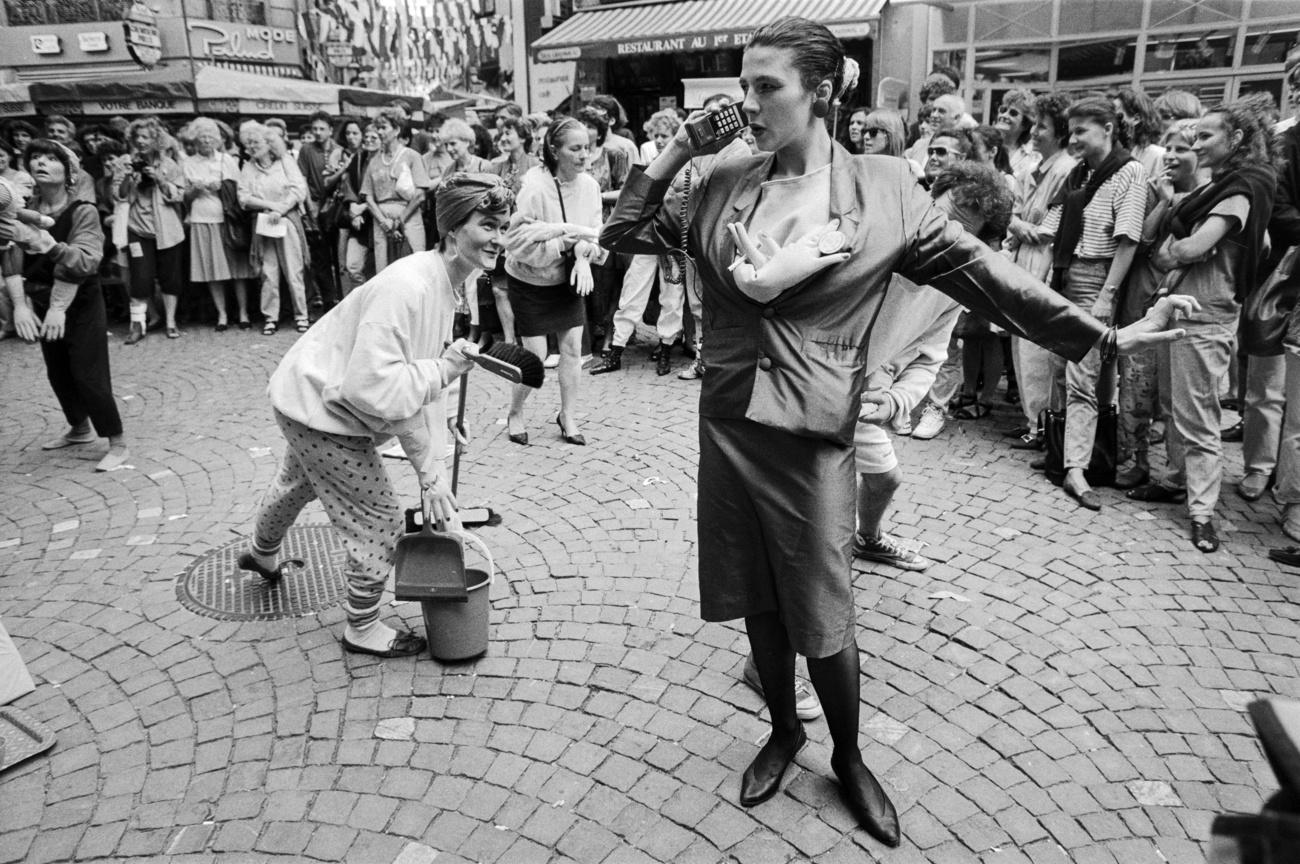

“Longchamp performs democracy,” was one journalist’s headline on a report about a city tour.

This multimedia series, which the author is producing exclusively for SWI swissinfo.ch, doesn’t concentrate on cities – instead its focus is on important places.

He also posts regular contributions on FacebookExternal link, InstagramExternal link and TwitterExternal link.

From 1803, the Helvetic Republic – after a brief civil war – was governed by a constitution in accordance with Napoleon’s “Act of Mediation”. Bern was now again just one city among many in the capital city stakes. There were now six cantons forming the directory (governing committee) and they took turns each year to nominate a governor, who acted as chair. Lucerne was one of these.

However, the federal treaty adopted by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 for the post-Napoleonic era did not include a governor. Zurich, Bern and Lucerne were to take turns at hosting the parliamentary assembly. There was no capital.

Yet the idea of becoming the nation’s capital had already taken root in Lucerne.

A second attempt ends in failure …

Lucerne’s second attempt came in the 1830s. This was a time of change. In 11 cantons liberal reform movements had carried the day. Representative democracy sprang up a cantonal level.

Until 1798, Switzerland had cities taking turns as the capital or as centres specialising in some administrative function for the Confederation. Since 1848, Bern has been the federal capital. The parliament and executive body (Federal Council) are based there, but not Switzerland’s highest court. Economic, military and cultural structures are decentralised.

All cantons except Appenzell Inner Rhodes have their own explicitly defined capital.

The more ambitious liberal plan of creating a new homegrown nation-state collapsed, however. It is true that in 1832 the federal assembly was considering a proposal for a federate republic with representative democratic institutions. It was also part of this proposal that Lucerne should be capital.

It did not work out. There was fierce criticism of the proposal. The conservative Catholic cantons thought it all went too far, while canton Vaud found the proposal too federalist. Lucerne itself got cold feet – there was concern that significant customs income might be lost under the new arrangement.

… and a third

Lucerne’s third attempt at being capital came at the end of 1848. The new federal state had just been founded. It had a constitution and Switzerland was now a representative democracy.

This of course did not all come to pass without a civil war of sorts. The conservative Catholic cantons – Lucerne among them – were against the new federation. A new wind was blowing. Since 1841, canton Lucerne had had an ultra-conservative government, and the city itself was ruled by an old-fashioned Catholic.

A conservative-democratic movement was gaining ground. Cantons Lucerne, Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden, Zug, Fribourg and Valais joined in a “separate confederacy”. This was supposed to defend the Catholic ethos of its members against the looming nation-state.

When news of the Catholic initiative broke, the federal assembly decided to put down this resistance militarily. The decisive engagement happened before the gates of Lucerne. The radical and liberal forces won. They assumed political leadership in all cantons, including Lucerne.

As a sign that canton Lucerne was now prepared to support the federal regime, the new government there proposed the city as a capital for federal Switzerland. But this went nowhere because of the hostility of the other cantons after the civil war.

Bern was chosen as the capital, which it remains to this day.

Birthing democracy

Several times, however, Lucerne had a decisive role in the birth of Swiss democracy. Democratisation, or the end of aristocratic rule, happened gradually and at cantonal level rather than centrally.

Liberals in Lucerne succeeded in democratising the republics, which had no process for further developing their constitutions. To this end the Lucerne liberals invented the people’s initiative, based on a rural movement. It had been part of the Lucerne cantonal constitution since 1831. And it stipulated that a constitution ratified in this way could not be changed for a period of ten years.

In 1841, conservatives struck back. They introduced a people’s right into the constitution: the veto. With this, (male) citizens could accept or reject new laws by a general vote. Anyone who abstained was deemed to have voted “yes” to the law.

Both of these mechanisms – the people’s initiative and veto – were not quite the citizens’ rights they are today. Decisions were not made by secret ballot, but with a show of hands at the citizens’ assembly. Today it would not be considered very democratic if all your neighbours saw how you voted.

Both these instruments were promoted by Ignaz Troxler, a doctor who had single-handedly started the liberal reform movement in Lucerne. Later he was a professor of constitutional law. He continued to support the conservative idea of the veto. He might be regarded today as a Christian Democrat philosopher. This meant he was in a position to speak with several of the ideological camps that had arisen.

Troxler made his greatest contribution in 1848. He proposed for the nation to adopt the American model of a two-chamber parliament. He advocated striking a balance between the principle of democracy and the principle of federalism.

Once achieved, this balance was one of the main reasons why the founding of the federal state in 1848 and the development of democracy actually succeeded.

Today Lucerne is the most important city for tourism in Switzerland. It just never managed to become the political centre of a democratic federation.

Adapted from German by Terence McNamee/gw

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.