Micro mines “pollute more” than commodity giants

Small mines scratched into the ground in poorly regulated parts of the world cause more pollution than large-scale operations, according to an environmental study.

The global gold rush is fuelling the problem by encouraging more micro-mining projects in developing countries. As a result, some 3.5 million people face death or disability from mercury poisoning, says Green Cross Switzerland.

More than 35 million people are at risk of dying from direct exposure to the ten worst toxins or having their lives considerably shortened, states the 2011 Top Ten Worst Toxic Pollution Problems Worldwide report.

The study, carried out by Green Cross Switzerland and the United States-based Blacksmith Institute did not look at general pollution caused by car or industrial output, but limited itself to toxins – such a mercury, lead and chromium – used in specific operations.

These were linked to mining and ore processing, metal smelting, chemical production, industrial and household waste, pesticides, battery recycling, petrochemical production and tanneries.

While most environmental reports tend to focus on the role of large-scale operations of multi-national giants, the latest research singles out small local projects for blame and even has praise for the improved record of globalised corporations.

Reckless exposure

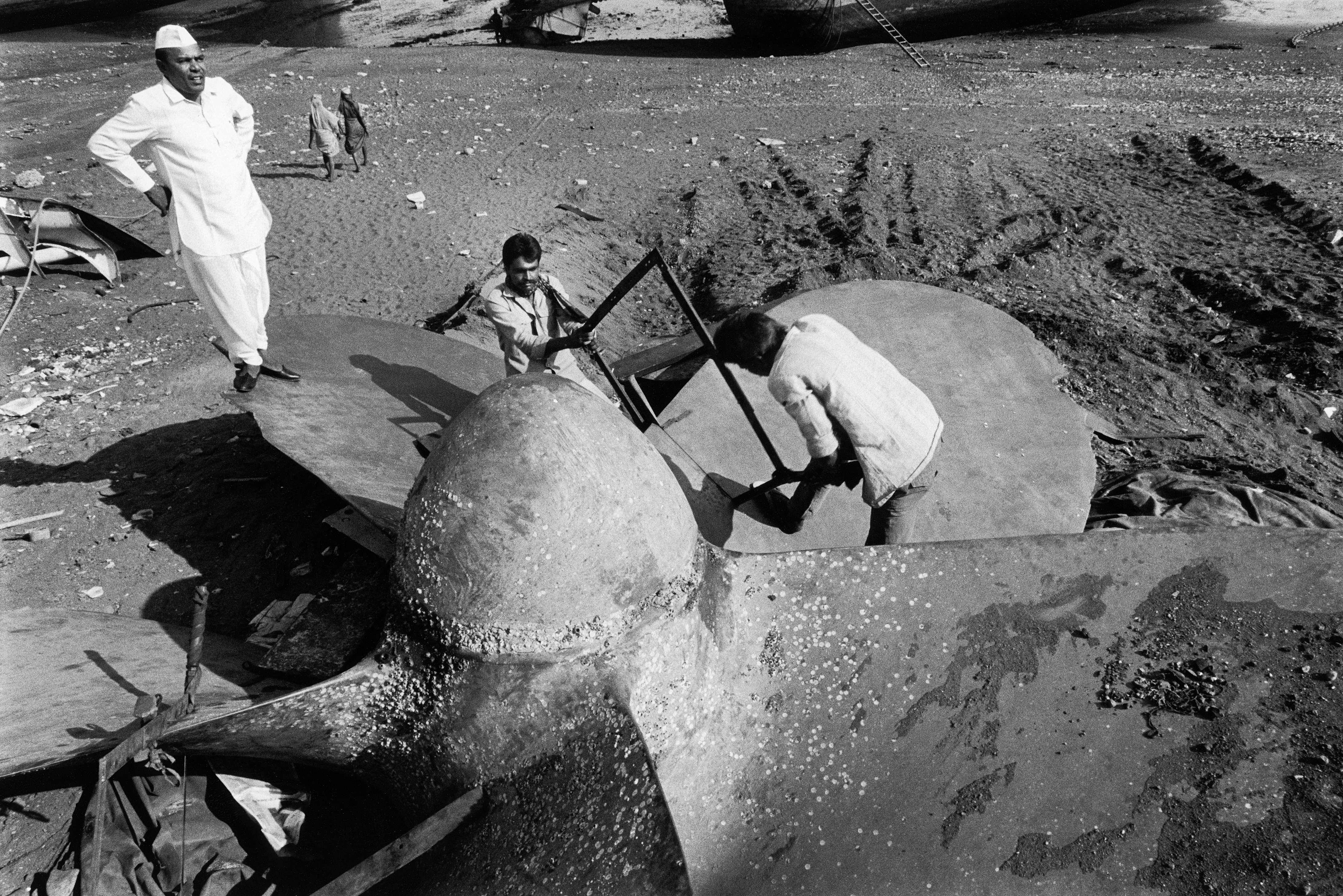

“Contrary to popular belief, many of the worst pollution problems are not caused by multi-national companies but by poorly regulated small-scale operations like artisanal mining, small-scale metal recycling and abandoned factories,” Green Cross Switzerland said in its introductory press release.

Most of the pollution takes place in low- or middle-income countries where people are more likely to take risks to earn money and where awareness of the dangers and regulation to control them are lacking.

In such instances, damage to health occurs either by workers mishandling toxins or neighbouring communities being exposed to substances via uncovered abandoned mines or leakage into water courses.

The report estimates that disabilities resulting from indirect exposure to these toxins shorten lives by an average 12.7 years.

The full range of unregulated mining operations endangers some seven million lives worldwide, according to the report. Green Cross Switzerland and the Blacksmith Institute are trying to raise awareness of the dangers and to work with the most at-risk countries to improve the situation.

Going public

Multinational mining corporations have been blamed for causing multiple deaths in developing countries by taking advantage of lax regulations.

Many such companies insist they have either cleaned up their act or have been forced to implement tougher codes of sustainability as a result of public outrage.

Nowhere can this be seen more readily than in publicly listed companies that are accountable to shareholders. Swiss-based commodities giant Glencore produced a lengthy sustainability report after it partially listed this year, outlining efforts to protect the environment and people living near its mines from damage.

But such assurances have failed to convince everyone. Swiss pressure group Berne Declaration pounced on Glencore’s report as being too vague and anchored in international standards that do not adequately reflect its operations.

But David Hanrahan of the Blacksmith Institute gave multinationals more credit – with the proviso that they still had a way to go before meeting full sustainability requirements.

Fatalities avoidable

“Big mining companies with a significant public shareholding are tending to get better and are putting in better controls,” he told swissinfo.ch. “Not unusually, big companies are subject to greater public scrutiny.”

“Smaller privately held mining companies have a tendency to find projects, develop them for profit and then sell out,” he added.

However, the developed world does not totally escape criticism in the report. There would not be nearly as many poorly run mines and other operations if it were not for the insatiable and increasing demand of developed economies for industrial minerals and investment in gold.

“High income countries are indirectly contributing to the problem in a significant way, as demand for commodities and consumer goods is largely driven by the economies of high income countries,” Green Cross stated.

Green Cross Switzerland and the Blacksmith Institute believe that more public attention and resources should be directed at the problem of pollution.

“The number of fatalities caused by pollution is comparable to the death toll of HIV or malaria,” said Stephan Robinson of Green Cross Switzerland.

“We have global programmes to fight and push back these health problems, but no such programme for pollution.”

Green Cross Switzerland and the Blacksmith Institute updated a 2008 toxic pollution report by gathering data from more than 2,000 sites around the world.

The report found that mining and ore processing operations are the most dangerous to human health, affecting 7.02 million people.

Metal smelting came in second place, with 4.95 million people at risk of death from severe health problems.

Some 4.78 million people live in the danger zone of chemical production sites while 4.23 million are in the firing line of small-scale artisanal mineral extraction projects.

Unregulated use of pesticides place 3.27 million people at risk and a further 3.21 million could be contaminated from industrial or household waste.

Heavy industry sites in developing countries, tannery operations and the petrochemical industry also affect millions more.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimated that toxic chemical exposure was responsible for 4.9 million deaths and the disability of 86 million other people in 2004.

Green Cross Switzerland and the Blacksmith Institute are working with organisations such as WHO and the Asian Development Bank to raise awareness in countries including India, the Philippines and Mexico and to improve regulations.

These agencies, and others, set up a health and pollution fund in 2007 aimed at raising $400 million (SFr362 million) aimed at tackling the problem.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.