Cut-throat cobalt drama will leave Congolese people the losers

Gertler, Gécamines and Glencore sound like the founding fathers of a crusty old law firm. In fact, they are among the principal actors in a cut-throat drama that will help determine not only the price of cobalt and electric car batteries, but also the political future of the not-so-Democratic Republic of Congo.

Who are they? Dan Gertler is an Israeli billionaire who, over two decades, has made himself the gatekeeper of Congo’s mineral wealth thanks to his close relations with the president.

Often under a cloud of suspicion, Mr Gertler was put on a sanctions list last year by the US Treasury, which said he had “amassed his fortune through hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of opaque and corrupt mining and oil deals”. Mr Gertler has always denied any wrongdoing, saying he deserves the Nobel Prize — presumably for peace, not fiction — for bringing billions of dollars to the Congolese people.

More

Financial Times

External linkGécamines is Congo’s state-owned mining company, without whose say-so few mining deals get done.

Glencore, meanwhile, is a buccaneering Anglo-Swiss mining and commodities trader that has been in business with Mr Gertler for a decade. In 2008, it took over Canada’s Katanga Mining, whose main asset is the giant Kamoto copper and cobalt mine, in which Mr Gertler already held a stake. It is also a joint venture partner of Gécamines, which has a 25% stake in Kamoto.

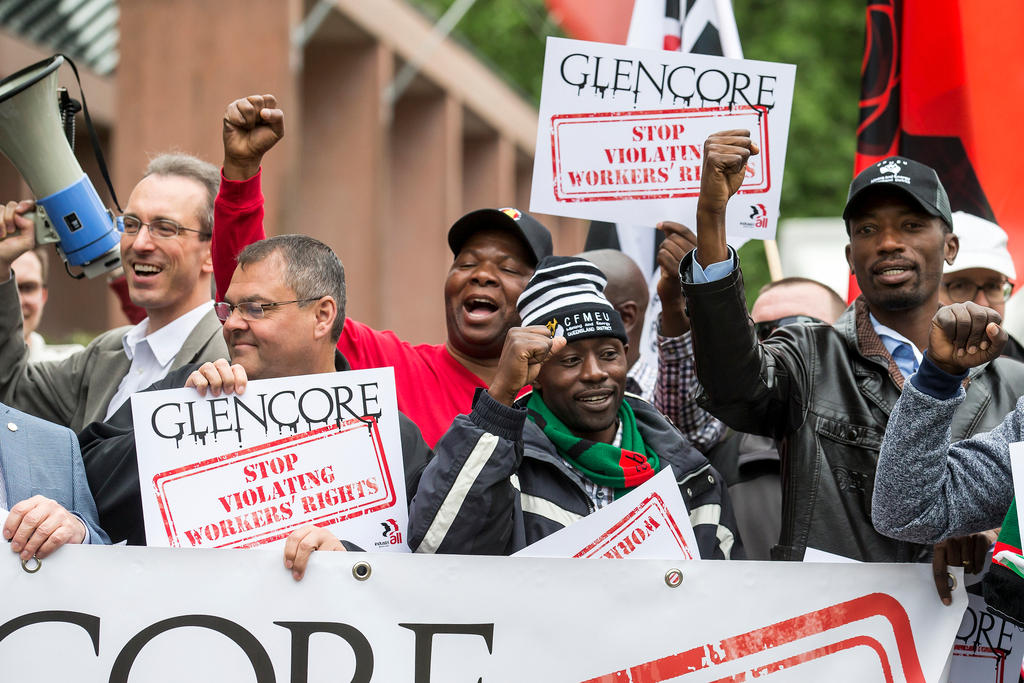

These ties are fraying. Last month, Mr Gertler began legal action against Glencore, claiming nearly $3 billion (CHF3 billion) in unpaid royalties. Glencore says it was forced to stop paying Mr Gertler because of US sanctions. Meanwhile, Gécamines is threatening to dissolve its joint venture with Glencore, accusing the Swiss company of “draining” the company of assets, thus squeezing dividends.

Call him “K”

Behind the three Gs is another actor. Call him “K”. Joseph Kabila has been Congo’s president since 2001, following the assassination of his father. He was supposed to have left office in December 2016, but elections to find his replacement never took place.

Working out what is happening in Congolese politics is like Kremlinology in the jungle, but something along these lines seems to be going on. Mr Kabila does not want to leave office. Not only is his own fortune and security wrapped up in the presidency, so is that of his family – several of whose members have profited from proximity to power.

But Mr Kabila’s thinking seems to have changed. After two years of putting off the elections, he is now racing towards them. The catalyst may have been the US move against Mr Gertler, which Mr Kabila could have interpreted as an attempt to squeeze his own finances.

Few think the president, who is constitutionally barred from running again, is simply going to bow out. One theory is that he will try to install a successor, although no credible name has emerged. Another is that he could hold provincial and parliamentary elections first, and hope to hang on – perhaps by amending the constitution.

Cobalt and cash

What does all this have to do with the three Gs? The unifying forces are cobalt and cash. To hold the elections on his own terms, Mr Kabila needs money. In Congo, that means minerals. Today it means cobalt, a key component of iPhones and electric batteries whose price has quadrupled since 2016 – and could rise again given events in the DRC.

Mr Kabila is pushing through a new mining code that will sharply increase royalties. Gécamines has made its move to dissolve the Glencore joint venture, in what could be a shot across the bows or even an attempt to wrest control of the giant Kamoto mine.

Meanwhile, the unrest that Mr Kabila has used as a pretext to postpone elections is spreading. Hundreds of thousands of people have fled fighting in central Kasai province. In the east of the country, guerrilla groups are on the move again. Ebola has broken out in Equateur province and, in North Kivu province, Africa’s oldest national park, Virunga, has closed after the killing of park rangers. As the western-Europe sized country lurches deeper into crisis, for most Congolese the prospects for education, health and jobs remain dire.

There could be winners from this mess. Glencore could still emerge with a grip over much of the world’s cobalt. The Chinese may also take advantage, tightening their stranglehold over processed cobalt and batteries. Even Mr Kabila’s plots to retain power could plausibly succeed.

The one group who are bound to lose are the Congolese people. They may be sitting on over 60% of the world’s cobalt – and thus the future of the auto industry for a decade to come. But as foreign companies, businessmen and the Congolese government scrap over the loot, it is they who will inevitably suffer.

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2018

More

Public Eye issues criminal complaint against Glencore

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.