Muslim cemetery demand sparks debate

The call for Islamic cemeteries in every canton by a Swiss Muslim umbrella group has provoked a wave of reactions.

Swiss Islam specialists say the legal strategy proposed by Farhad Afshar, president of the Coordination of Islamic Organisations in Switzerland, is the wrong approach to an inexistent problem.

On Sunday Afshar told the Sonntag newspaper he was preparing a legal case concerning freedom of religion after the Bernese commune of Köniz recently rejected a separate burial ground for Muslims.

“With this strategy we are turning something into a problem that isn’t one really – it’s a clumsy approach,” said Stéphane Lathion, head of a research group on Islam in Switzerland at Lausanne University.

Lathion said a federal solution was particularly inappropriate, as in 90 per cent of cantons where there had been discussions about Islamic cemeteries, solutions were found that satisfied everyone.

Nine communes in the cities of Zurich, Bern, Basel, Thun, Lucerne and Geneva have special cemetery space set aside for Muslims. Islamic law says Muslims should be buried separately from people of other faiths.

Burial space

But Afshar says he has received many complaints from Muslims in Switzerland. “Muslims who came here 40 years ago are dying and have the right to be buried with dignity,” he told the Tribune de Genève newspaper.

Nobody is putting into question the right to a decent burial, said Andreas Tunger-Zanetti, from the Religion Research Centre at Lucerne University, but the legal approach is the wrong one.

“Swiss regulations and Muslim requirements can normally be reconciled, but this has much to do with the needs at the local level and these are defined by the authorities and Muslim representatives,” he noted.

“The numbers may increase in the years to come, but there is no use trying to have one fixed solution for the whole of Switzerland. In some cantons there are hardly any Muslims; one shouldn’t exaggerate the issue.”

Lathion went even further: “There is no demand – 90 per cent of Muslims who die in Switzerland are repatriated.”

Both experts felt Afshar was not very representative of Switzerland’s 400,000 Muslims, mainly from the former Yugoslavia and Turkey.

Political storm

Meanwhile, in political circles the question of religious cemeteries continues to provoke heated debate.

“Right until death, Muslims want to create a parallel structure,” the rightwing Swiss People’s Party parliamentarian Oskar Freysinger told the Tribune de Genève newspaper.

Green parliamentarian Daniel Vischer felt Afshar’s legal strategy had little chance of success, while his colleague Antonio Hodgers warned it risked “getting the population’s back up”.

“I would put Ashfar’s declaration in the same category as those made by Christophe Darbellay the evening of the minaret vote,” said Lathion. “It’s one-upmanship rather than an attempt to make people understand or explain what is happening.”

In December 2009 Christian Democratic Party President Christophe Darbellay called for a ban on new Muslim and Jewish cemeteries, just days after Swiss voters approved a halt to building new minarets. He later apologised.

Muslim reactions

Afshar’s comments have provoked a mixed response in the Swiss Muslim community.

While the question of Islamic cemeteries is relevant, his strategy and timing are flawed, said Abdel Lamhangar, a Swiss Muslim and Socialist councillor for Romont, in canton Fribourg.

“The country is under pressure from all sides and it’s not the moment to have another legal tussle,” he told the French-speaking national radio show Forum.

And Afshar should recognise that Swiss culture is one of negotiation and consensus, he added.

“When things are imposed by the judicial system it’s the rule of law, but when they are imposed by negotiation it’s adhesion and the building of a future,” he said.

Hafid Ouardiri, general-secretary of the Geneva-based interfaith foundation Entre-Connaissance, said in theory Afshar had the right to defend his religious difference, but his method was perhaps wrong.

“Before going to court you need to think about other ways,” he said. Ouardiri highlighted the example of Geneva, where after a long political battle fought jointly by the Muslim and Jewish communities, the local government granted both special burial grounds in a state cemetery in May 2007.

For Swiss Jewish communities Geneva is a special case; in Zurich, Basel and Bern, they have their own cemeteries built on private land, explained Nicole Poëll, deputy president of the Platform of Liberal Jews in Switzerland.

“For us the issue of religious cemeteries is not an issue – it’s been resolved,” said Poëll.

Simon Bradley, swissinfo.ch and agencies

The Muslim community in Switzerland accounts for about 4.5% of the population.

Most Muslim immigrants came from the former Yugoslavia and Turkey. The community includes up to 100 nationalities.

The number of Muslims doubled between the censuses of 1990 and 2000, largely boosted by an influx of refugees and asylum seekers, including from the war in the former Yugoslavia.

There are about 200 mosques and prayer houses in Switzerland, but only four have a minaret.

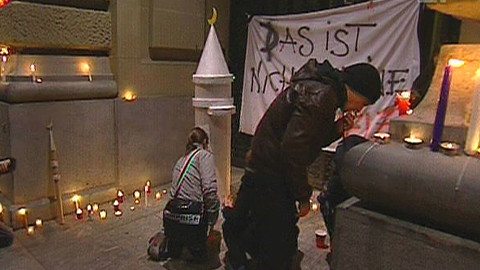

On November 29, 57 per cent of voters supported a people’s initiative to ban the construction of new minarets in Switzerland. This was in the wake of heated debates and legal battles at a local level about requests by mosques to build more minarets.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.