Why the Swiss would rather protect whisky than wolves

Livestock owners are likely raising a glass to toast lawmakers who on June 11 took clear aim at Switzerland’s meagre wolf population. Their choice of tipple? Possibly homemade spirits that could soon be afforded the kind of protection canis lupus can only dream of.

It seems to be a case of economic interests trumping ecological concerns.

Here’s why

While wandering through the Alps in 1995, a few young male wolves ventured over the border into Switzerland from Italy. If they had known there was such a line, and all the fuss they were about to cause, they may never have crossed it.

Conservationists and wildlife lovers cheered their returnExternal link. The wolf had been hunted down and driven out of the country in the 19th century. Yet livestock farmers and breeders loathed its comeback, and made their contempt known loud and clear when the animals followed their instincts.

In their first year back on Swiss soil, the predators were linked to the killingExternal link of nearly 120 sheep.

Since then, conservationists and the livestock lobby have been at each other’s throats. For their part, the pro-wolf groups have praised the ecological benefit, arguing that farmers can erect fences and deploy sheepdogs to protect their herds.

The farmers have repeatedly fired back, and questioned the effectiveness and affordability of such measures, demanding a weakening of the law that protects wolves.

So, who’s crying wolf?

But the biggest battles have been fought on political stages, both Swiss and European.

Switzerland has twice taken the case to the Council of Europe, requesting a change to the Bern ConventionExternal link. This legally binding treaty, ironically named after the Swiss capital, commits signatories to the conservation of flora and fauna. Switzerland has argued that wolf populations across much of western Europe have sufficiently recovered to justify their downgrading from “strictly protected” to just “protected”.

How many is too many? Have you had an encounter with a wolf?

In some states wolves now number a few hundred, or at the upper end of the scale, such as in Italy or Poland, around 2,000.

So how many wolves pose such a threat to livestock in Switzerland, the country spearheading the anti-wolf campaign? Not more than 50.

Switzerland failed to win enough support when it first brought the motion to Strasbourg in 2005, and its renewed request late last yearExternal link was postponed by the Council’s standing committee.

But this hasn’t stopped Swiss lawmakers from circumventing the convention.

While the executive, the Federal Council, believes Bern, the seat of government, should still commit to Bern, the treaty, the two chambers of parliament have now weakened the criteria for deciding when an animal can be hunted down.

Protecting cherry brandy

Only a couple weeks before the decision on the wolf (and bear, but that’s a different story) the Federal Council recommended that Switzerland sign up to another treaty, this one too named after a Swiss city.

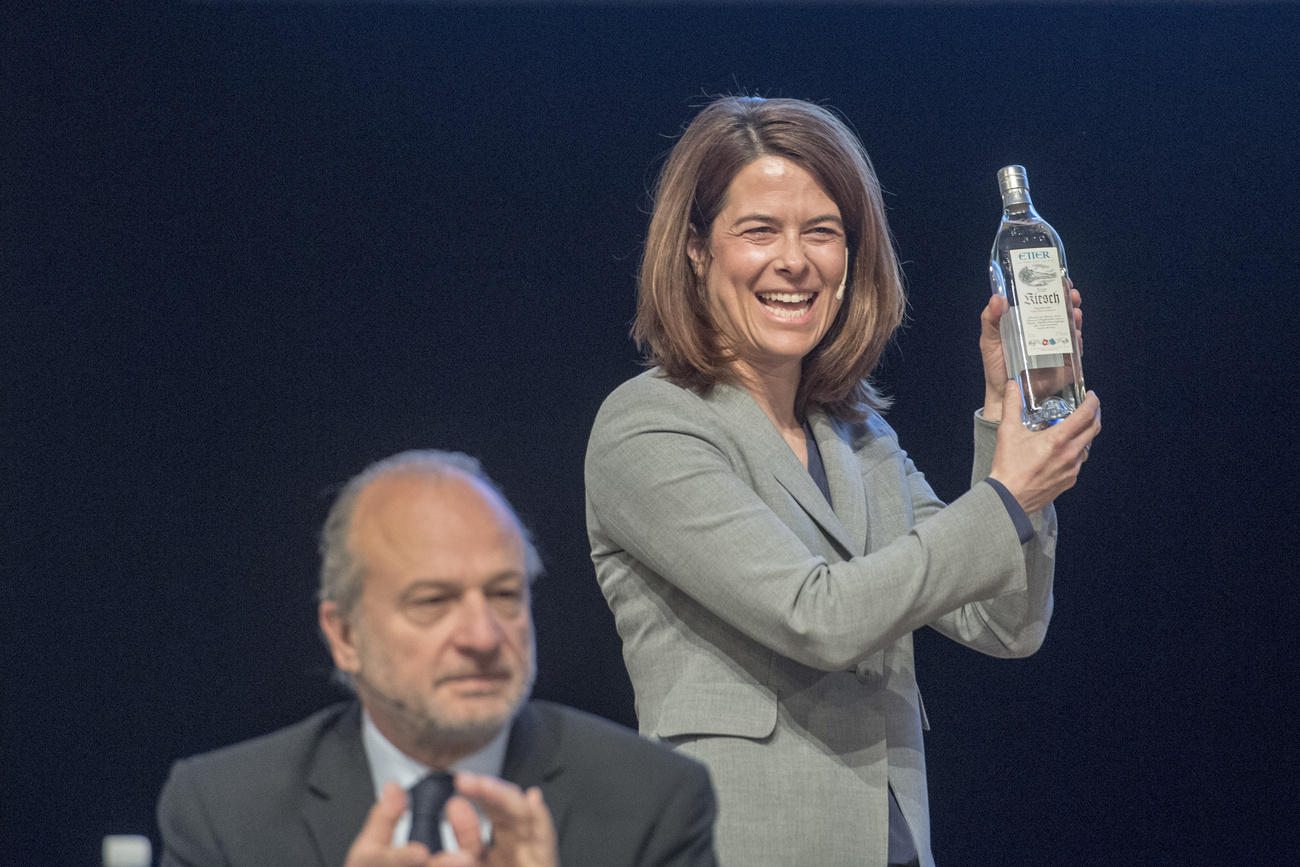

The Geneva ActExternal link, it can be argued, is to Swiss cheese, air-dried beef and kirsch (ok, it’s a brandy not a whisky) what the Bern Convention is supposed to be for otters, wild flowers and wolves.

The agreement, reached in 2015, extends protection given to traditional products that are tied to a specific place. Think Champagne. A bottle of bubbly from anywhere other than France’s Champagne region is just another sparkling wine.

In Switzerland’s case, the government listed Tête-de-Moine (a semi-hard cheese), Bündnerfleisch (air-dried beef), and Zug and Rigi Kirsch as examples of products vulnerable to imitation.

If stakeholders and parliament agree, Switzerland would be among the first countries to accede to the treaty later this year, securing the future for the owners of cherry tree plantations and cheese makers.

Stay tuned. The wolf can only look on with envy.

Contact the author at dale.bechtel@swissinfo.ch or on twitter @dalebechtel

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.