Parliamentary lobbyists to face closer scrutiny

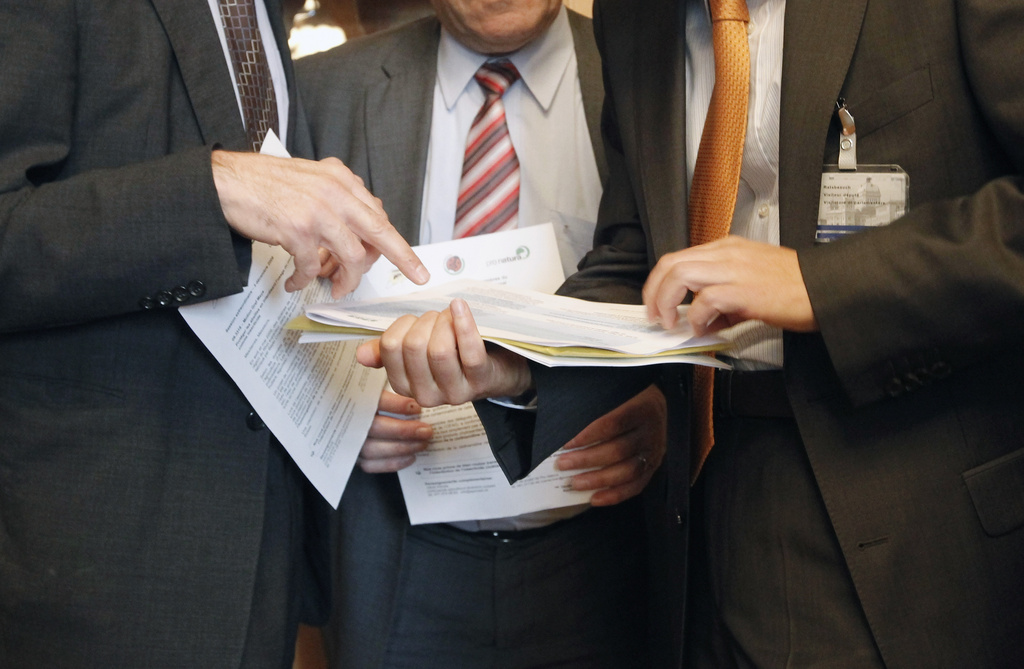

Swarming with people when in session, lobbyists and PR hacks allowed through the doors of federal parliament often fly under the radar as they try to wield influence.

But two months ahead of parliamentary elections in October, questions are being raised about the independence of Switzerland’s politicians, and in particular the amount of power lobbyists and interest groups have on the way they cast their votes.

Essentially part-timers, Swiss parliamentarians are being called to vote on increasingly complicated issues that are often well outside their purview of local issues.

Lacking the time or resources to dig up information needed to cast an informed vote, lobbyists and interest groups have stepped into the void, according to professor Andreas Ladner of the Swiss Graduate School of Public Administration.

“Politicians need information and they don’t have parties which are very strong and have lots of people working in different fields who can guide them,” Ladner told swissinfo.ch.

“So they have to turn towards people who know much more and usually these people have their [vested] interests.”

But many of the people thronging around parliament are not professional lobbyists, according to Fredy Müller, president of the Swiss Society for Public Affairs (SSPA), an umbrella group for lobbyists representing some 220 groups. Instead, many are company marketing people or are working for other interest groups.

Who are you?

Müller said the SSPA has called several times for parliament to create a register or accreditation system for lobbyists and other groups, in the interests of greater transparency.

“I would like to know, as a professional lobbyist, who is in parliament,” Müller said. “There are so many people in the building and most of them are not lobbyists. More importantly, who will influence discussions and debates? Are they registered somewhere? We would like to make it transparent what we are doing.”

Pulling no punches, parliamentarian Lukas Reimann has launched a multi-party initiative – not supported by his own rightwing Swiss People’s Party – which is aimed at forcing parliamentarians to declare from whom they receive perks and other benefits, as well as potential conflicts of interest when sitting on committees.

“I have seen so many examples of politicians not doing what they want or what is good for the people, or the country. They just decide what to do because they have been paid by lobbyists,” Reimann told swissinfo.ch.

Reimann has also called for a register for lobbyists and interest groups. Other politicians on the left have lodged similar initiatives calling for lobbyists to be accredited in the same way as journalists.

The calls have not fallen on completely deaf ears – a list of who has access to the parliament building, and which politicians invited them in, will be available on the internet from 2012.

Part-timers

Being a Swiss parliamentarian has always been a part-time job and members earn their main living elsewhere. In the current parliament, they are listed as working in management, agriculture, the law, unions, education and health, to name just a few.

“Some of these parliamentarians are on the payroll of very important firms,” said Ladner. “When it comes to deciding in commissions, especially where we don’t really see what’s going on, perhaps they become more representative of their firm and less representative of their electorate.”

Ladner said problems of transparency lie in the fact that while the information about who works for who is available, it is not easy to find. He said other countries are “more advanced on transparency” than Switzerland.

Reimann agreed: “In Switzerland, you see nothing. It’s really difficult when you do a search. Secrecy is very big and that has to change. It’s also dangerous because of corruption.”

While conceding that more transparency about the role of lobbyists generally is needed, Müller said the system of checks and balances in the Swiss democratic system ensured that blatant corruption would not pass.

If you want to influence a politician, said Müller, it’s not enough to simply hand out a pamphlet and buy lunch, as politicians are always wary of being called out for bias.

“In Switzerland, you still have to fight with arguments. You can’t buy politicians,” he said.

Resistance and credibility

Müller said some politicians are resisting calls for greater transparency because of various reasons. He said the issue goes to the heart of the credibility of the democratic system and voters’ confidence in it.

”We have more and more of a reputation problem because normal voters don’t understand who is doing what in politics,” Müller said. “For the voters, we have to make it clear, we have to have a list that shows voters the connections [politicians have]. It’s not the lobbies that have to decide this, it is a question that has to be decided by the politicians themselves.”

Ladner suggested that in some cases politicians may be reluctant to reveal more about their external influences on ideological grounds – that the state should not meddle in private affairs.

“But the others who say ‘I don’t want to say where I get my money from because otherwise I won’t get reelected’, I think then you really have a problem and transparency is necessary,” Ladner said.

The 200 seats in the House of Representatives are allocated according to the size of the population in the 26 cantons. Every canton – or constituency – is entitled to at least one seat.

The system of proportional representation was introduced in 1919 and – unlike Germany for instance – there is no minimum threshold of votes for a party to gain a seat.

In principle cantons have two seats in the Senate except for six small so-called half-cantons which have one seat each. Elections to the Senate vary from canton to canton, but they all use the first-past-the-post system.

Of the 200 members of the House of Representatives:

24 work in agriculture or related industries;

33 work in management;

30 work in the legal profession;

15 work in education;

24 list their sole occupation as politics;

19 work for unions or associations.

Others are employed in IT, transport and business, media, social sciences and health.

Source: www.parlament.ch

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.