Foreigners stuck in an asylum limbo

Over the last ten years, Switzerland has given more than 43,000 asylum seekers the provisional right to remain. But many cannot go home, and the strict limits placed on what they are allowed to do leave them in a state of uncertainty.

“My husband was a political dissident. He received multiple death threats and decided to seek refuge in Europe. I followed shortly afterwards, after I was also targeted,” said Keicha*. Born in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Keicha sought asylum in Switzerland in 1996.

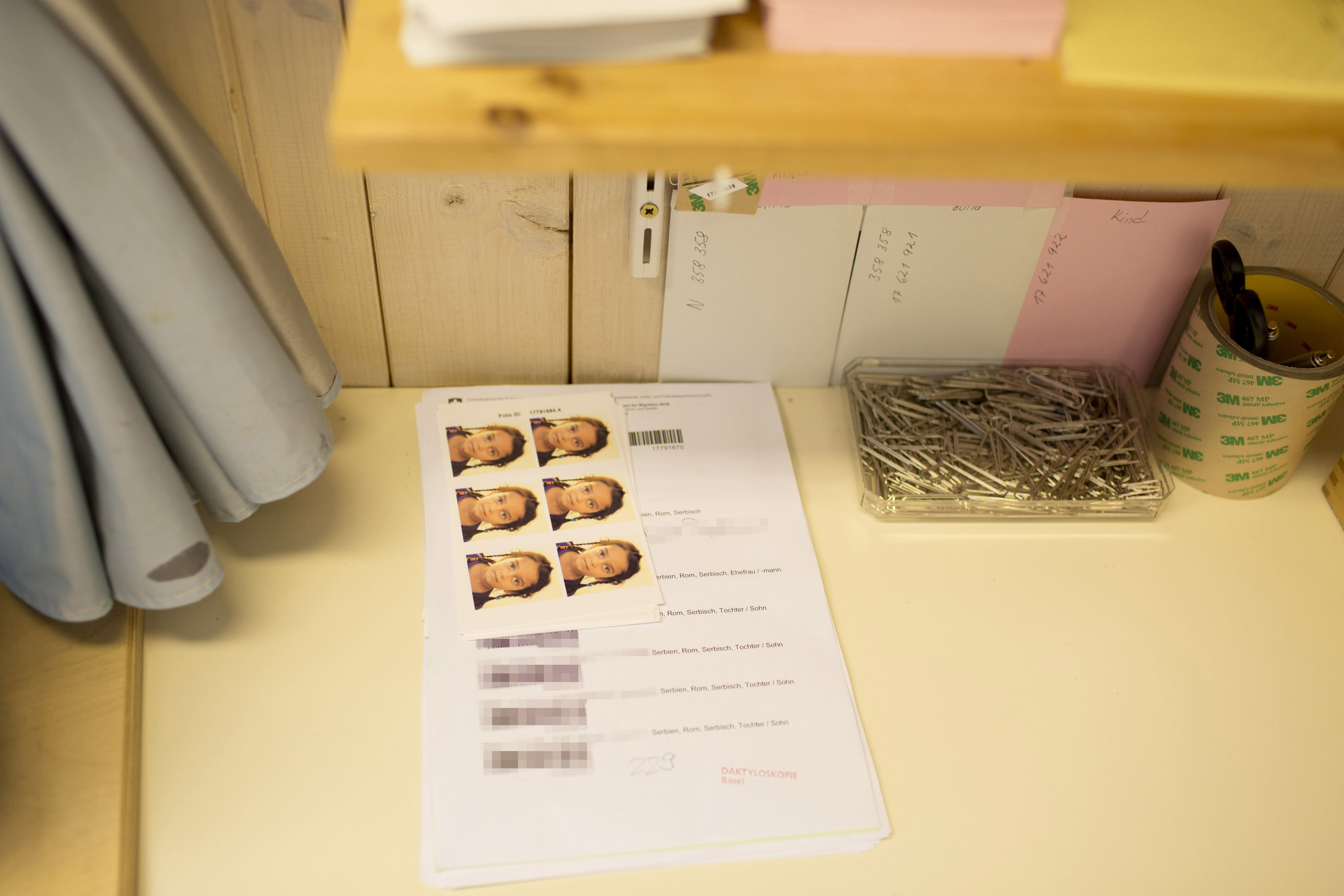

After a six-year wait, she received an F Permit – the permit for provisionally admitted foreigners – in 2002. This meant that although the authorities had denied her refugee status, they had suspended repatriation because she was considered in need of temporary protection.

At that time the DRC was in a state of civil war. “Returning would have put my life and those of my family at risk,” Keicha added in a telephone interview with swissinfo.ch.

The F Permit was created in the mid-1980s to deal with conflicts that were not covered by the Geneva Conventions. It was called “provisional” because it was supposed to be issued for a short period, and it gave fewer rights to its holders compared to refugees who are granted automatic permission to stay.

Never-ending

In reality, admission is provisional in name only – around 90 per cent of rejected asylum seekers end up staying in Switzerland mainly because conflicts in countries such as Somalia and Afghanistan have been going on for decades.

The Federal Migration Office also does not have the means to review individual cases every year. “We have to work according to priority and taking into account the principle of proportionality,” spokeswoman Céline Kohlprath explained. Repatriation becomes more difficult as time passes.

In all, 43,619 foreigners have been granted a F Permit in the last decade, compared with 24,240 gaining refugee status. Some F Permit holders gain permission to stay after a minimum of five years by having shown that they are well integrated and economically independent. But others find themselves stuck in a kind of admission limbo for many years. At the end of 2012 there were 22,600 F Permit holders, around half of whom had been in Switzerland for more than seven years.

“It’s a vicious circle: it’s not easy to find a job with a F Permit. And if you don’t have a stable income or decent salary it’s almost impossible to change your status in a short time,” said Lucine Miserez Bouleau from the Protestant Social Centre in Geneva, which helps immigrants.

This happened to Keicha, who is still “provisional” after 16 years in Switzerland. With only CHF3,200 ($3,443) a month and three children, she does not have the financial security to be granted a permanent residence permit.

Political steps

The topic has recently been debated in parliament – but there is a radical difference between the solutions being proposed. The political left and humanitarian organisations favour a boost to the status by improving rights and integration measures, but the right and centre-right want to tighten admission criteria and checks.

There was a substantial reform of provisional admission in 2006, when parliament granted the right to professional and social integration. But despite efforts, not much has changed in practice, according to the Federal Migration Office and the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs in a booklet on the F Permit.

“There are many solid obstacles – common to many immigrants from conflict countries – like the difficulty of getting over trauma, of getting your qualifications recognised, if you have them, and learning a new language. It’s often the case that these people are refused a job, even very low-paid ones, because of their provisional status,” said Denise Efionayi-Mäder, deputy director of the Swiss Forum for Migration and Population Studies in Neuchâtel.

“This is a problem that doesn’t just affect adults, but also young people who have grown up in Switzerland who have a F Permit and who are looking for apprenticeships.”

Sometimes social security is the only option.

Usually refugee status is accorded in Switzerland in cases of serious persecution targeted a the specific individual by the state or by private entities against which the state is powerless to act.

Provisional admission is granted to people who have not been given asylum but whose repatriation is considered “inadmissible” or “unreasonable”.

Reasons include a general violent situation, such as in Syria, a risk of torture or persecution, or if someone does not have access to indispensible medical treatment.

Job search

“It’s often happened to me that as soon as I show the F on my blue permit, the door has been slammed shut in my face. I have the impression that people don’t know what it is and are afraid of being left in the lurch,” said Komin*, who fled Togo in 2002 for political reasons.

Swissinfo.ch met him in Fribourg, where he works as a care assistant. “I have always tried to be economically independent, right from the beginning: I have worked as a dishwasher, a handyman and have in the meantime managed to finish Geneva University. It has been hard, but worth it.”

Komin was granted residency two years ago, an important turning point. “Perhaps it’s just psychological, but since my status has changed, I have had the feeling that people look at me differently,” he said.

For employers, hiring someone with a F Permit involves wading through a lot of red tape and longer waiting times. There is also competition from workers coming from the European Union, who benefit from the free movement of people. This situation has been confirmed by a spokesman for Adecco, the leader in temporary staffing, and the Swiss Union of Arts and Crafts, which represents the small and medium enterprises in Switzerland.

Parliament has once again started to debate provisional admission as part of the revision of the asylum and naturalisation law.

Under discussion is whether to accord residency automatically to provisionally admitted foreigners, after a certain time and if repatriation is not possible.

The right wing Swiss People’s Party is calling for stricter admission criteria and checks, “The authorities should check every three to six months if a person should return to their homeland,” said the party’s Hans Fehr. The party has not ruled out launching an initiative to abolish provisional admission.

The centre-right parties say that provisional admission cannot be compared to refugee status. “This would be akin to increasing the right to asylum and Swiss voters have said many times that they do not want that,” said the Radical Party’s Isabelle Moret.

At the end of 2012 Switzerland reintroduced the rule preventing F Permit holders from travelling freely abroad, after having suspended it for three year years. Several members of parliament had submitted motions in favour of the ban.

Some members of parliament want to limit access to naturalisation, especially for the younger holders. They are also to have their say on a People’s Party proposal which seeks to ban family reunification for those admitted provisionally.

Limited movement

The F Permit also restricts a person’s movements. As with asylum seekers, provisionally admitted foreigners are obliged to stay and work in the canton to which they have been “assigned”, so that the burden is shared across cantons and communes. This still applies after decades of living in Switzerland.

Provisionally admitted persons, including those born in Switzerland, are also only allowed to leave the county in exceptional circumstances and under certain conditions. This measure was reintroduced last December following concerns raised by centre-right politicians about possible abuses of the system.

For those affected it is difficult to accept. “I felt as if I was in prison, shut away,” said Saida Mohamed Ali. “Paradoxically, it was this that gave me the strength to go forward. I said to myself, I’ve got this far, I’m still young, I don’t have a choice, I have to find a way.”

Saida left Somalia in 1993 when civil war was raging. She lived for many years with an F Permit, before gaining residency and eventually becoming Swiss.

“I think I managed to succeed because of my passion for studying, my skill at learning languages and also thanks for the generosity of the people I have met. In Africa people think of Switzerland like in the films, a little paradise where everything is possible. In reality, you are thrown in at the deep end. Some manage to swim on their own. Others need a life belt that is bigger than a simple F Permit.”

*Name changed

The EU guarantees “subsidiary protection” to persons fleeing conflict. With this status they have right of residence for three years.

Norway (not an EU member) does not distinguish between refugees and persons in need of protection. Other countries grant the same rights to both groups, but maintain the distinction.

According to the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Switzerland is the only country in Europe, besides Liechtenstein, which does not accord a “positive” status to people fleeing conflict. “These people show up in the statistics as rejected asylum seekers, and in public debate are seen as wishing to abuse the right of asylum,” says Susin Park, head of the UNHCR office for Switzerland.

The UNHCR believes people admitted provisionally have the same needs as refugees and should have the same rights.

(Translated from Italian by Isobel Leybold-Johnson)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.